Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI

FASHION FILMS. FASHION'S ANTIDOTE TO COMMUNICATION CRISIS SITUATIONS

FASHION FILMS. ANTÍDOTO DE LA MODA ANTE SITUACIONES DE CRISIS DE COMUNICACIÓN

![]() Pablo Martín-Ramallal: University Center San Isidoro, attached to the University Pablo de Olavide. Spain.

Pablo Martín-Ramallal: University Center San Isidoro, attached to the University Pablo de Olavide. Spain.

![]() Mercedes Ruiz-Mondaza: School of Higher Artistic Education. Spain.

Mercedes Ruiz-Mondaza: School of Higher Artistic Education. Spain.

How to cite the article:

Martín-Ramallal, Pablo, & Ruiz-Mondaza, Mercedes (2024). Fashion Films. Fashion's antidote to communication crisis situations [Fashion Films. Antídoto de la moda ante situaciones de crisis de comunicación]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 57, 1-21. http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2024.57.e865

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Fashion, as an essential component of cultural fabric, was drastically impacted by the crisis triggered by the pandemic. In response, brands adapted, turning to fashion films (FF) as a means to maintain visibility of their collections in a context of social distancing, thereby solidifying their presence on social media. Methodology: The study was based on the analysis of 44 FFs published on YouTube between mid-2020 and late 2022. It was supplemented with a Likert questionnaire directed at 162 experts and educators to gather perceptions of their impact. This mixed methodology, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches, allowed for understanding how FFs became a crucial tool during the health crisis. Results: FFs proved effective in overcoming communication barriers during the crisis, leveraging their ability to spread widely on social media. The convergence of branded content and transmedia amplified their impact, especially among younger generations. Results indicated a positive reception and high propagability of these 2.0 audiovisuals, positioning them as an effective tool for addressing adverse situations. Discussion: The adaptability of FFs during the crisis underscores their ability to maintain brand relevance in a changing environment. The convergence of marketing strategies has contributed to their success, although it's crucial to consider their future evolution and effectiveness in different contexts. Conclusions: In summary, fashion films have proven to be a valuable tool for addressing communication challenges during the pandemic. Their ability to maintain brand visibility in difficult times and their widespread acceptance among audiences suggest they are an effective strategy for maintaining public engagement in adverse times.

Keywords: fashion film; crisis communication; transmedia; branded content; fashion collection; social networks.

RESUMEN

Introducción: La moda, como componente esencial del entramado cultural, se vio impactada drásticamente por la crisis desencadenada por la pandemia. En respuesta, las marcas se adaptaron, recurriendo a los fashion films (FF) como una forma de mantener la visibilidad de sus colecciones en un contexto de distanciamiento social, consolidando así su presencia en las redes sociales. Metodología: El estudio se basó en el análisis de 44 FF publicados en YouTube entre mediados de 2020 y finales de 2022. Se complementó con un cuestionario Likert dirigido a 162 expertos y docentes para recopilar percepciones sobre su impacto. Esta metodología mixta, que combinó enfoques cualitativos y cuantitativos, permitió comprender cómo los FF se convirtieron en una herramienta crucial durante la crisis sanitaria. Resultados: Los FF demostraron ser efectivos para superar barreras comunicacionales durante la crisis, aprovechando su capacidad para difundirse ampliamente en las redes sociales. La convergencia del branded content y el transmedia amplificó su impacto, especialmente entre las generaciones más jóvenes. Los resultados indicaron una recepción positiva y una alta propagabilidad de estos audiovisuales 2.0, lo que los posiciona como una herramienta efectiva para abordar situaciones adversas. Discusión: La adaptabilidad de los FF durante la crisis resalta su capacidad para mantener la relevancia de las marcas en un entorno cambiante. La convergencia de estrategias de marketing ha contribuido a su éxito, aunque es crucial considerar su evolución futura y su eficacia en diferentes contextos. Conclusiones: En resumen, los fashion films han demostrado ser una herramienta valiosa para enfrentar desafíos comunicacionales durante la pandemia. Su capacidad para mantener la visibilidad de las marcas en momentos difíciles y su aceptación generalizada entre las audiencias sugieren que son una estrategia efectiva para mantener el compromiso del público en tiempos adversos.

Palabras clave: película de moda; comunicación de crisis; transmedia; contenido de marca y firma; colección moda; redes sociales.

1. INTRODUCTION

The digital native (Prensky, 2001) and the new generations understand Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) as something natural and innate and fashion is the intentional mirror of their personality (Lurie, 2013). In a space where videos and social networks converge in an inalienable way, FFs become first-order promotional stories for the fashion sector (Jódar-Marín, 2019a), among others, for their aesthetic, sensual and communicational virtues. To such an extent their boom in 2020, at the height of the pandemic, they were substitutes for conventional fashion shows (EFE, 2020), which had to be reinvented (Cristófol-Rodríguez et al., 2022). This reality does not escape the Spanish context (Viñarás-Abad and Llorente-Barroso, 2020). According to Jiménez-Marín and Elías-Zambrano (2019, p. 46) "fashion collections are places where styles, uniforms, trends, culture or folklore are recycled". Taking this statement into consideration, the pandemic has permeated the textile space, influencing its communication patterns at all levels. Advertisers have become aware of this by generating an unprecedented wave of original advertising actions, such as those based on extended realities (virtual reality, augmented reality) or advergames (advertising video games) as in the case of Balenciaga, inspired by Animal Crossing (Gibson, 2021). Sometimes, advertisers even generate serialized pieces, as Tous did with Tender Stories (2014-2017) (Méndiz-Noguero et al., 2018). Transmedia (Alberich-Pascual and Gómez-Pérez, 2017), branded content and other digital entertainment (Bertola-Garbellini and Martín-Ramallal, 2021; Cendoya, 2018) are an effective formula to create links and build engagement with targets (de Aguilera-Moyano et al., 2015) in a context of media and channel metamorphosis (Sánchez-Mesa, 2019). Brands, more so fashion firms, must develop content that is appreciated by their consumers (Kam et al., 2018) in what we understand as transmedia universes, whose essence must be maintained (Corona-Rodríguez, 2016; Notario-Rocha, 2019).

Fashion communication that aims to be successful has to materialize disruptive actions and campaigns to stand out and attract attention, in a sector where transgression and creativity are the flagship. This became more evident within a confining scenario in which it was necessary to reinvent oneself (Zhou et al., 2022). Faced with bewilderment, many brands resorted to FFs, asking directors and scriptwriters, according to Portaluppi (Vistelacalle, 2021, para. 2), to promote "the value and symbolism of those hugs we are going to give each other when we return to normality, taking care of ourselves, staying at home, using the mask. Maybe the idea is already repeated". However, this sector tries to avoid commonplaces, so it transmits these values, but from lateral thinking (de-Bono, 1991), i.e., fleeing from conventionalisms. Moreover, when the pandemic suggests moving into the endemic phase in 2022, it is clear that fashion designers are once again going their own way, each setting their own trend.

2. OBJECTIVES

The purpose of this article is to determine the suitability of FF as transmedia and branded content narratives to overcome communicational obstacles derived from social crisis situations. It is necessary to promote the suitability of these narratives because they have their own and increasingly prominent space in the fashion world. In order to achieve this goal, this article will examine the influence of the pandemic on the development of FFs as substitutes and complements to the launching of fashion collections and how they have adapted their narratives to overcome the adverse discourse in which the promotion of the sector was found.

The research hypothesis is that:

- H1. FFs are an element of outreach that fashion brands should consider during the restrictions imposed in crisis situations that limit the conventional modes of social communication.

3. METHODOLOGY

The study eminently adopts a mixed qualitative-quantitative system. Given the inalienable nexus of fashion as a first-order social agent at present, the deductive method is assumed, a perspective admitted as valid for this type of objects (Hernández-Sampieri, 2018). From this perspective and with a descriptive-explanatory approach (Bernal-Torres, 2016), a content analysis is carried out (Krippendorff, 2018), based on the viewing of 44 cases of communication of various fashion brands during the periods of confinement and social distancing caused by the health crisis. Several of the fashion audiovisuals were selected as participants of the Fashion Film Festival of Milan (FFF Milano, 2021, 2022, 2023). The 2020 edition had to be postponed without time to look for alternatives. The 2021 and 2022 editions saw the launch of the Digital Awards, which shows the strong influence that Covid-19 had on the creation and spread of the FF. To that extent, the fashion films studied were made between mid-2020 and 2023, at which point the endemic was passed and the global health emergency was lifted. That same year the FFF Milano returns to its face-to-face format with the novelty of adding virtual reality creations and a metaverse of the event. The scope of the exhibition seems adequate because it complies with the principle of saturation which determines that, after a certain number, the data it yields will be redundant, losing effectiveness by repeating efforts in the technique used.

The interpretation model is based on a visual content analysis carried out according to the hermeneutic system, since flexibility is granted to the authors relying on their research background and knowledge on the subject. Connotative aspects are observed through an iconic approach based on the ideas of Barthes (1986), considering its universality and relevance in the digital context. The elements examined include: image, pose, synthesis, and iconicity. A perspective that integrates connotation with proxemia, kinesics, and scenography is provided. Regarding image, FF images were selected, considering those that highlighted relevant aspects of the collections or conveyed pandemic-related messages, and their visual composition, aesthetic quality, and ability to communicate the essence and message of the collection or brand were evaluated. Regarding the pose, attention was paid to scrutinize expressive poses that contributed to the visual narrative in terms of values. They were evaluated from perspectives of expressiveness, elegance and coherence with the theme of the collection in the COVID-19 context. In relation to synthesis, we focused on the FF's ability to condense and express the essence of the brand-collection, observing moments that captured the intended message, and evaluated how it managed to communicate the brand's identity and message, according to the theme. Finally, in terms of iconicity, elements with qualities to become icons were identified.

As the dependent variable, the study establishes the perception that professionals and teachers have about the matter, as well as the impact that the crisis has had on fashion communication according to the perception of the industry’s experts. Likewise, the authors considered the specific elements of the FF narratives during the study period as the independent variable. For the selection of items, the authors carried out a non-probabilistic intentional sampling (Otzen and Manterola, 2017) based on the relevance of the brand, the reach of the campaign-collection, the transmedia approach and link with mental and visual pandemic-related elements. As mentioned, FFF Milano was a very important source, but authors also searched on YouTube. As for the big companies, in 2020, the fashion house Gucci presented Ouverture of something That never ended, while Chanel launched Over the moon and Métiers d'art show. Louis Vuitton presented The adventures of zoooom with friends, and Cartier stood out with How far would you go for love. Hermès projected When Kelly came to town and The girl with the Black Bag. Dior presented Le Château du tarot in 2021, while Tiffany & Co. released About Love and Tiffany's Table manners for teenagers. Contrast, Perfect Light was Luis Vuitton's most significant production in 2021. The study analyzed all nominees and winners of 2021, 2022 and 2023 FFF Milano, as in the case of the 2021 winning Aspesi brand entitled The life and times of mannequin town. When analyzing these FFs, the authors realized that large luxurious houses do not communicate in the same way that companies with a more transgressive approach.

The social network replication control tools have been useful to quantitatively verify the expansion of the communication initiative. Without any statistical intention, and based on the interpretation of the authors, once the analysis of the 44 FF was done, a questionnaire was sent to 162 fashion professionals and teachers to confront the hypotheses and results obtained from the study. The participants were also chosen consciously due to their particular characteristics that made them relevant to the study, so that again there was intentionality. The questions have been validated by research experts in the field of communication and design. This form is based on a five-level Likert (Leung, 2011) where five indicates full agreement with the statement exposed and one means a frontal rejection. For its dissemination, telematic tools are used to obtain the tabulated data that will be presented as results. After contact, informed consent and explanation of the test, participants were given a Google Forms to answer a 5-level Likert questionnaire with the 15 key questions of the study. It is assumed that a score equal to or lower than three and a half is a negative value, since this type of questionnaire has the problem of scoring them upwards.

As a novelty, the study presents an unprecedented contribution to the field of science by focusing on the role of FFs during the context of the pandemic from a perspective on how these audiovisuals have become a fashion communication tool, examining their influence and effectiveness in the promotion of brands and collections. Previous research tends to focus on luxury and the general public (Cenizo-Ruiz-Bravo, 2022), whereas this paper is conducted from a general view and focused on the perception of professionals. Moreover, by incorporating the voices and experiences of these people linked to fashion, the article provides a practical and applied vision. It highlights the growth of FFs, their diversification in styles and themes, and their interaction with digital platforms, identifying emerging trends in fashion communication.

4. MATERIALS

4.1 Definition of concepts

To frame the study conveniently, a series of fundamental concepts are established for the full understanding of the article. First of all, FFs must be understood as another phenomenon and player in the advertising landscape, since they have a strategy and a commercial purpose supported by a media plan, something essential in fashion as an entity dependent on the modern status quo (Velasco-Molpeceres, 2021). But what is advertising? To admit that it is:

The display of advertisements and persuasive messages, in time or space, purchased in any of the media by for-profit businesses, nonprofit organizations, government agencies and individuals seeking to inform and/or persuade members of a particular target market or audience about their products, services, organizations or ideas (AMA, 2022).

Following on, and given that it is an idea of interest, transmedia will be understood generically from the position of Jenkins (2006, p. 2), for whom it is "that process where the integral elements of a fiction are systematically dispersed through multiple distribution channels with the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment experience". The term has gained great relevance and is one of the axes of postmodern advertising. However, in an effort to adapt to the current context, we subscribe to the definition of Alberich-Pascual and Gómez-Pérez, as they go further with a general and conciliatory approach:

Transmedia communication expands into a revolutionary mosaic of pieces narratively linked to each other, open to interaction and expansion in the hands of its potential users, which opens up significant processes of change and redefinition of roles in the framework of contemporary creative industries, thus giving rise to a long series of industrial, cultural, and finally aesthetic implications of revolutionary scope that it is essential to address. (Alberich-Pascual and Gómez-Pérez, 2017, p. 10)

Given the relentless effort to readapt brands, it is essential to understand what branded content is, since it is a way of transmitting brand values with a high appeal and that is not entirely linked to advertising (Sanz-Marcos and Micaletto-Belda, 2019). For Pineda-Cachero et al. (2013, p. 70) "it is based on the integration of the values of a brand in messages that do not possess a priori an advertising nature". Regarding insights, Castelló-Martínez (2019, p. 32) defines it as "truths and/or subjective experiences that are revealing and relevant to the consumer, based on deep motivations that, used in persuasive communication, allow reinforcing the link between brand and consumer, connecting with the consumer as a person".

4.2 Fashion films

As their own translation into Spanish indicates, FFs are short fashion films (Jódar-Marín, 2019b) where the articulation of audiovisual language is key to achieving their objectives, understood from a marketing promotion perspective. Its duration is usually about three minutes, but in some cases brands opt for longer productions with resources typical of a big-budget film, as is the peculiar case of Contrast, Perfect Light by Luis Vuitton (2021) (Figure 1). Del-Pino and Castelló (2015, p. 18), define them as a " form of short films, at the service of a brand, characterized by a communicative style in which the beauty and extremely careful aesthetics of the message predominate over the product and/or the brand itself". Meanwhile, Jódar-Marín (2019a, p. 182), understands them as "the result of the new opportunities offered by the Internet, addressing the needs of a new audience that demands new content, demonstrating the process of adaptation of fashion brands to the new communicative ecosystem". This type of videos merge art, cinema, music, fashion and advertising (Arbaiza-Rodríguez and Huertas García, 2018). Often, their intention is to approach digital audiences that have grown up alongside 2.0 technologies (Castelló-Martínez and Del Pino-Romero, 2019). For Jódar-Marín (2019a, p. 167):

they are created following a demand, as a new way to express the image of fashion and brand values through a plastic presentation of high aesthetic quality, based on a versatile and innovative format conceived for the Internet.

Figure 1.

Peculiar Contrast, Perfect Light by Luis Vuitton (2021).

Source: Font in Use (2021). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vV_QoQD_nrA

The channels offered by new technologies provide an unparalleled discursive and rhetorical variety, where the audiovisual embodied by homo videns (Sartori, 2012) takes on an unprecedented prominence. Fashion brands have always found in the audiovisual one of their greatest allies, but it is nowadays when they achieve the greatest persuasive capacity and impact among audiences, which can become standard bearers given the diffusing properties of social networks. Gamifying brands and entertaining targets is a growing resource that is proving to be appropriate in cybersociety, especially in the case of fashion (Kam et al., 2019). Advertising must be attentive to this type of situation where hypermedia narratives such as FFs are emerging exponentially. This type of communication is beginning to be used as one more gear of advertising transmediality and, little by little, will increase its prominence.

Advertisers now have another resource at their disposal that can achieve unprecedented diffusion and penetration thanks to platforms such as YouTube. This capacity can be amplified because, if the millennials make photography 2.0 part of their story through manifestations such as the selfie, the following generations (z and t) adopt video as a prosumer language (Jenkins, 2006) as exemplified by TiKToK (Martín-Ramallal and Ruiz-Mondaza, 2022) and the adaptation of the hegemonic social networks to this ideology.

4.3 Fashion films, collections and crisis situations

The fashion industry has been one of the hardest hit after the outbreak of the pandemic in March 2020. As people were unable to show off their clothes beyond their family space, investment fell disproportionately. Brands such as those in the Inditex group, which seemed eternally bullish, saw their sales drop dramatically (Isla, 2020) despite the support of the online channel. Collections developed in 2019 remained orphaned or in the designers' workshops. Far from resigning themselves, countless creators are turning to FFs as a lifeline (EFE, 2020). Shot in real bubbles in the style of Hollywood blockbusters, there was a boom in fashion films. Rarely have brands had such generous budgets to promote their new ideas.

During 2020 and 2021, the various fashion weeks adopted a hybrid format between face-to-face and online, with digital creative content gaining relevance. ICT and creativity have served as allies to solve or, at least, alleviate the intrinsic problems of this adverse situation (Martín-Ramallal and Merchán-Murillo, 2020). Some even went as far as betting on virtual worlds with collaborations with such popular titles as Fortnine (Epic Games, 2017).

5. RESULTS

During the fieldwork, 44 YouTube FFs, launched from mid-2020, 2021 and part of 2022, a period marked by the pandemic, have been visualized. This time interval has been chosen because the audiovisuals produced should have an intentionality marked by the pandemic and not be the result of or derived from previous projects. The authors determine that, after the analytical observation of the 44 audiovisuals, values such as love, friendship and other affective bonds seem to be determinant in the FFs launched in this period. The narratives have not been excessively influenced, although, evidently, some of the videos show some kind of link with what happened during these years. Where narratives mediated by the events have been perceived is in the FFs of minor and even amateur brands, as many people locked up by the mandatory confinement turned their creativity and concerns into this type of pieces. The contents were very imaginative and showed how to exploit homemade resources in an interesting and fun way, but their dissemination and professional level were scarce. What is unequivocal is that the number of fashion audiovisuals, including FFs, has grown significantly. Many of the big companies have made very large production boasts, resulting in an evident budget increase in these marketing and branded content actions. Consequently, everything seems to indicate that the objectives and hypotheses have been successfully covered.

5.1. Likert Questionnaire

The statements made to the different experts try to give part of the answer to the hypotheses raised. As stated, they are not of a statistical nature given the size of the sample, but they do have relevance because the questionnaire was completed by people with extensive experience in the fashion industry, so they acquire the category of heuristics. Professionals and teachers were questioned, avoiding convenience. The profiles of the volunteers have been contrasted and all their opinions add value to the study. Contact with the interest group was made in person, by telephone call or through social networks. All participants willingly accepted and were informed that the data would be treated in accordance with the Data Protection Act (Informed Consent). At the end of the form sent, there was an open-ended question about the relationship between the FF and the launch of collections during the pandemic.

The following section specifies the variables and equations used in the Likert questionnaire (see Table 1). A neutral or negative rating was considered if the score was below 3, given that this system tends to increase the scores. Ten statements are presented below, six of which seek to consolidate the cases presented. Subsequently, quantitative results are presented in terms of totals, averages and percentages. Table 2 is approached through the process of hermeneutic interpretation of the data, an appropriate approach due to its flexibility, which encourages discussion and gives relevance to the researchers' experience (Bernal-Torres, 2016). It is essential to highlight that the statements were written in an understandable way for people unfamiliar with the concept of branded content or with immersion itself. In addition, the study allowed for personal interaction with most of the participants, some of whom expressed skepticism and criticism towards virtual reality and metaverses related to the field of fashion.

Table 1.

Variables and formulas for Likert interpretation.

|

Variables |

Fomulas |

|

S: Sample (x participants) |

RTP= (L1T)+(L2T)+(L3T)+(L4T)+(L5T) |

|

Ln: Likert (up to 5) |

Avg.= T / S |

|

LnT: Likert n Total |

Net Stmt.=(L1T*1)+(L2T*2)+(L3T*3)+(L4T*4)+(L5T*5) |

|

Stmt Maximum possible: Stmt. MP. |

T. Mn= Net Stmt. / Nº Stmt. |

|

T. Mn: Total Mean |

Mn.Stmt. = T. Mn / S |

|

Mn.Stmt.: Mean statement |

O%= (Net Stmt. * 100) / Stmt.MP |

|

O%: Overall percentage |

RTP= (L1T)+(L2T)+(L3T)+(L4T)+(L5T) |

|

T: Totals per statement |

Avg.= T / S |

|

Avg.: Average |

Net Stmt.=(L1T)+(L2T*2)+(L3T*3)+(L4T*4)+(L5T*5) |

|

%Stmt: Percentage of statement |

T. Mn= Net Stmt. / Nº Stmt. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Table 2.

Likert of statements related to the study.

|

Statements |

<Low |

|

High> |

||||||

|

L1 |

L2 |

L3 |

L4 |

L5 |

Mean |

||||

|

Stmt1. The pandemic has affected fashion. |

0 |

8 |

29 |

46 |

79 |

4,21 |

|||

|

Stmt2. The pandemic has affected the launch of collections. |

0 |

1 |

35 |

37 |

89 |

4,32 |

|||

|

Stmt3. Technologies mitigate the effects of the pandemic on fashion. |

0 |

5 |

27 |

79 |

51 |

4,09 |

|||

|

Stmt4. Fashion has more ways to communicate than ever. |

0 |

2 |

14 |

55 |

91 |

4,45 |

|||

|

Stmt5. FFs serve to gain fashion relevance. |

0 |

10 |

35 |

45 |

72 |

4,10 |

|||

|

Stmt6. FFs mitigated the effects of COVID-19 in fashion. |

2 |

13 |

25 |

61 |

61 |

4,02 |

|||

|

Stmt7. FFs have gained prominence with the pandemic. |

0 |

9 |

9 |

91 |

53 |

4,16 |

|||

|

Stmt8. FFs generally deliver a positive message. |

0 |

2 |

27 |

63 |

70 |

4,24 |

|||

|

Stmt9. Themes of FFs have been affected by fashion. |

2 |

7 |

81 |

47 |

25 |

3,53 |

|||

|

Stmt10. FFs are a resource that is here to stay. |

0 |

5 |

27 |

54 |

76 |

4,24 |

|||

|

Stmt11. FFs depend on the diffusion in networks in order to succeed. |

0 |

0 |

40 |

90 |

32 |

4,24 |

|||

|

Stmt12. Influencers and fashion media are key to its success. |

0 |

5 |

25 |

74 |

58 |

3,95 |

|||

|

Stmt13. FFs without the support of broadcasters do not succeed. |

1 |

8 |

40 |

59 |

54 |

4,14 |

|||

|

Stmt14. The main FF platform is YouTube. |

0 |

23 |

58 |

63 |

18 |

3,97 |

|||

|

Stmt15. Fashion week and media websites are critical for successful FF dissemination. |

0 |

0 |

19 |

107 |

36 |

3,47 |

|||

|

|

POSSIBLE Stmt. |

TOTAL Stmt. |

NET Stmt. |

Mn.T |

Mn.Stmt |

O% |

|||

|

|

12150 |

2430 |

9905 |

4,1 |

660,333 |

81,52 |

|||

|

Stmt. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

|

Total |

682 |

700 |

662 |

721 |

665 |

652 |

674 |

687 |

572 |

687 |

687 |

640 |

671 |

643 |

562 |

|

Average |

4,21 |

4,32 |

4,09 |

4,45 |

4,10 |

4,02 |

4,16 |

4,24 |

3,53 |

4,24 |

4,24 |

3,95 |

4,14 |

3,97 |

3,47 |

|

% |

84,2 |

86,4 |

81,7 |

89,0 |

82,1 |

80,5 |

83,2 |

84,8 |

70,6 |

84,8 |

84,8 |

79,0 |

82,8 |

79,4 |

69,4 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

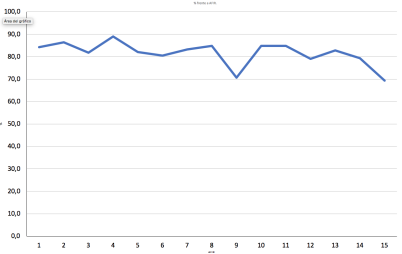

Figure 2.

Percentage of acceptance of statements (Stmt.%).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Based on the data, the study yields the following results:

- The pandemic has affected fashion (Stmt1). As an opening remark, all interviewees acknowledged that the pandemic had been a determining factor during the 2020s and well into 2021, still raging at the time of this writing (2023). This statement obtained a high level of acceptance (84.2%). Experts acknowledge that the pandemic has had a significant impact on the fashion industry.

- The pandemic has affected the launch of collections (Stmt2). This statement also had a high level of acceptance (86.4%), indicating that the pandemic has influenced the launch of new fashion collections. Tangentially, the launch of collections had suffered irreparable damage in 2020 with the decline being minor in 2021. Even those participants in the expert questionnaire who were not exclusively dedicated to the fashion world, as is the case of teachers, appreciated this because of the very low visibility of this type of promotional actions. In the personal talks, all the professionals openly acknowledged that their activity had been affected by an unprecedented event, and that only state support measures such as the ERTEs served to mitigate the situation.

- Technologies mitigate the effects of the pandemic on fashion (Stmt3). ICTs became a bastion of communication and commerce. Many reinvented themselves and began to conduct their business through e-commerce or telepresence channels such as Zoom. The crisis allowed the integration of new digital techniques, which have become part of everyday life. Videos on networks, without reaching the sophistication of the FF, were also a tool. Small fashion designers, far from the resources of large firms, have had to learn new 2.0 communication models that are now part of their daily lives.

- The majority of participants (81.7%) agree that technologies have helped to mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic on fashion. There was a broad consensus that the new technologies served to partially alleviate the problems derived from such a difficult situation, but that in no case did they serve to avoid the tsunami in the sector.

- Fashion has more ways of communicating than ever (Stmt4). Whether producing or consuming them, most of the people interviewed recognize that FFs have experienced an overwhelming growth, with an unknown quantity of pieces, variety of styles, and number of options. In addition, the quality of the audiovisuals is high, which indicates a high level of training and audiovisual culture in the textile design and accessories industry. This statement received a high level of acceptance (89.0%), reflecting the perception that fashion has diversified its forms of communication, possibly driven by technological evolution. Some of the participants appreciated the number of productions emerging from the academic field.

- FFs serve to gain fashion relevance (Stmt5). The statement has a high acceptance (82.1%), indicating that FFs are considered suitable for increasing relevance in the fashion industry.

- FFs mitigated the effects of COVID-19 in fashion (Stmt6). Specifically, with respect to whether FFs mitigated the effects of the pandemic on fashion, no one could answer in first person, although they do admit that from a global point of view they appreciated huge efforts in this regard, and that, especially in 2021, when the big brands were prepared, they were able to unveil their collections at times that were supposed to be similar to what was known as the old normal.

- Although with a slightly lower acceptance (80.5%), most experts still agree that FFs played a positive role in mitigating the negative impacts of COVID-19 on fashion.

- FFs have gained prominence with the pandemic (Stmt7). The questionnaire revealed that FFs have become more spectacular and, also significantly, the perception that their number has increased during the pandemic is widespread, as well as the fact that people on the street know the term. The statement obtained a high acceptance (83.2%), suggesting that, according to the perception of the participants, these audiovisuals have gained in spectacularity during the pandemic.

- FFs generally deliver a positive message. (Stmt8). The majority of experts (84.8%) agree that FFs usually convey positive messages in their content.

- Themes of FFs have been affected by fashion. (Stmt9). However, except for some exceptions, this is not considered to have influenced the subject matter too much, without falling into characteristic items of adversity such as masks or social distancing, but quite the opposite. What does seem to be a widespread perception is that FFs are going to be generalized as a way of publicizing the collections, but as a support. Acceptance of this statement is somewhat lower (70.6%), indicating that the pandemic may have influenced the themes addressed, although with some variability of opinions.

- FFs are a resource that is here to stay (Stmt10). The majority of study participants believe that FFs need some support to stand out and that they may not have enough push to be sufficiently relevant on their own. This statement received a high acceptance (84.8%), reflecting the idea that these films have established themselves as an enduring tool in fashion communication.

- FFs depend on the diffusion in networks in order to succeed (Stmt11). The statement has a high degree of acceptance (79.0%), indicating that the diffusion in social networks is considered crucial for the success of FFs. Influencers and fashion media are key to its success (Stmt12). Although with a somewhat lower acceptance (82.8%), most experts still agree that the involvement of influencers and fashion media is important.

- FFs without the support of broadcasters do not succeed (Stmt13). The statement received a high level of acceptance (79.4%), indicating that the support of broadcasters is a determining factor for the success of these fashion films. It is essential to have some broadcasting strategy, which suggests that transmedia may be the natural habitat of FFs, especially those that aim to have a wide impact among 2.0 audiences.

- The main FF platform is YouTube (Stmt14). Although with somewhat lower acceptance (69.4%), most experts agree that YouTube is the main platform for FF spreading. It is peculiar, given that the authors did not detect it, that YouTube is no longer the hegemonic platform. It is true that it is very important, but you have to count on the support of sites such as Instagram or TiKToK, especially if you intend to reach a younger audience.

- Fashion week and media websites are critical for successful FF dissemination. (Stmt15). It is not the same for corporate sites, as it follows that they must continue to be relied upon despite the relevance of social networks. The same goes for fashion week sites and the necessary support from the media, whether generalist, specific or digital natives. The acceptance of this statement is lower (63.8%), indicating that there is some variability of opinions on the importance of fashion week websites and the media in the successful spread of FFs.

5.2. Answers to the open-ended question

The form includes an open-ended question. "How do you think FFs have affected the launch and/or helped fashion collections during the pandemic?". The responses reflect a positive and widespread perception towards FFs as narratives that have definitely integrated into fashion communication and help circumvent crises. We will now interpret the most outstanding responses as they confer value to the research and constitute a primary source, especially due to the professional nature of the fashion industry:

- Recognition of the importance of communication platforms and social networks. The importance of adapting to communication platforms and social networks for fashion communication is highlighted. The undeniable relevance of advancing in this constantly changing market is recognized, underlining the need to consider inappealably the social networks.

- Reinvention of FFs in the pandemic. The categorization of FFs as a film genre that has reinvented itself during the pandemic is highlighted. Its key role in the communication of large firms and its innovative approach is pointed out, which helps to visualize the essence of brands. The invasion of other more immersive FF models is also mentioned.

- The FFs as a new way of making fashion. The responses reflect the evolution of FFs as a new way of doing fashion. They are perceived as a trend for advertising collections, providing an immediate presentation of the image of the collection. FFs have become essential for brand presentation, reflecting a transformation in the fashion advertising narrative.

- Resources for weathering the storm. FFs are recognized as a fundamental resource for weathering the storm of the pandemic. Brands, especially those with fewer resources, are managing to make proposals even in home environments. The central role of video networks in providing visibility in times of constraint is highlighted.

- Contribution to visibility and demand. The contribution of FFs to the visualization and demand for fashion collections is highlighted. This is not limited only to large brands, but extends to medium and small companies. The FFs are consolidated as an advertising tool that generates attraction and incites consumption.

- Creativity without the need for large means. Creativity is presented as a key factor in the production of FF, and it is emphasized that no great means are needed to produce them. A fashion designer, with a phone and good ideas can make an impact. The equality of fashion and FFs in terms of creative expression is underlined.

- The fundamental role of social networks. The active link with the networks is considered basic for an effective promotion. The combination of social networks and FF is seen as essential for companies seeking to adapt to a diversified advertising environment.

- Accessibility and potential for global diffusion and virality. The accessibility of FFs stands out, acknowledging that large resources are not needed to develop effective advertising campaigns. It is emphasized that both students and international firms can leverage ingenuity and ideas to be seen by a wide audience through 2.0 channels.

- Conceptualization, transgression and adaptation to current media. FFs manifest themselves as advertising tools capable of being conceptually transgressive and regenerated by other modern media. The commercial and marketing strategy considers transmedia environments and even virtual reality to maximize impact.

In summary, and as important ideas, it can be concluded that FFs are appreciated as a narrative that has been definitively implemented in crisis situations and is not necessarily seen as something typical of big brands.

6. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In terms of discussion, following the results obtained, it finds support in the studies presented on the convergence between fashion and audiovisual media, particularly FFs. Supported by Jódar-Marín (2019a) and del-Pino and Castelló (2015), the evolution of FFs has been pointed out as a response to the demands of a constantly changing digital society. The adaptation of fashion brands to the communicative ecosystem, highlighted by Jódar-Marín (2019a), is supported by the findings of this study, where fashion films are perceived as a relevant communication tool, at the same time as being an appropriate narrative as an advertising strategy in contexts of widespread communication crises.

According to the results, FFs are part of a new fashion communication consumption, taking into account the new ICT and the digital revolution. Given the interest they arouse, their peculiarities in terms of production and the ease offered by social networks for their dissemination, they have become an alternative to be considered to overcome communication problems such as those caused by the pandemic.

The article allows determining that the first hypothesis, which indicates that FFs have become a communicational system to disseminate fashion and its collections has been effective and recurrent during the pandemic, consolidating itself as a preventive alternative for future crisis situations, seems to be affirmatively solved. The evidence gathered supports H1, demonstrating that FFs have evolved into an important communicational tool during crisis situations, such as the pandemic, where social constraints demanded alternative approaches to promotion. The adaptation of brands to the communicative ecosystem through their transmedia and hypermedia capabilities, highlighted in previous literature and validated by the study, reflects the ability of FFs to fill communication gaps and overcome obstacles in the dissemination of fashion collections. At the time of writing this study, the trend of FFs as consolidated and growing stories continues, so everything seems to indicate that they are here to stay. Indeed, it has also been proven that circumstantially some of the narratives and scripts of the FF have been influenced by connotative elements derived from the crisis itself, such as the concept of social distancing. It seems certain that the FF during the pandemic have seen their themes influenced by the health crisis in a minority and marginal way, giving priority to positivity and brand values. The negative aspects have been largely ignored. It can be affirmed that the messages generally appeal to empathy, love, and assertiveness with others.

The study has shed light on several areas of interest in the field of FF and fashion communication. As future lines of research, the authors assume as a new route given their teaching facet to include the development of FF as learning tools, both creative and from critical thinking. It would be necessary to explore how these films can be effectively integrated into education and training in fashion design and communication, taking advantage of their potential as learning tools. It is also of interest to address phenomena such as hyperdiegesis, and how this could be implemented in FFs as they already do in mainstream platforms (Martín-Ramallal et al., 2019).

As a result, several research lines for the future have been identified. One of the most prominent, derived from hypermodernity, would be to delve into the application of hyperdiegesis in FFs, studying how this narrative technique can redefine the viewer's experience. Analyze how it can be implemented in an adequate and useful way, generating application cases in platforms that support this procedure (Martín-Ramallal et al., 2019). At the same time, their effectiveness as a marketing strategy and how they compare with other advertising media could be researched. The adaptation of dissemination techniques in various digital platforms is another topic worthy of research. Finally, to argue that the integration of emerging technologies such as virtual and augmented reality would have the quality of opening new immersive possibilities for viewers, something that deserves further analysis. These areas offer fertile ground for future research in the field of FF and its impact on fashion communication.

7. REFERENCES

Alberich-Pascual, J. y Gómez-Pérez, F. J. (2017). Tiento para una Estética transmedia. Vectores estéticos en la creación, producción, uso y consumo de narrativas transmediales. Tropelías: Revista de Teoría de la Literatura y Literatura Comparada, 28, 9-20. https://doi.org/10.26754/ojs_tropelias/tropelias.2017282044

AMA (2022). Advertising. AMA. https://www.ama.org/topics/advertising/

Arbaiza-Rodríguez, F. y Huertas-García, S. (2018). Comunicación publicitaria en la industria de la moda: branded content, el caso de los fashion films. Revista de Comunicación, 17(1), 09-33. https://doi.org/10.26441/RC17.1-2018-A1

Barthes, R. (1986). Lo obvio y lo obtuso. Imágenes, gestos, voces. Paidós Comunicación.

Bernal-Torres, C. A. (2016). Metodología de la Investigación. Pearson.

Bertola-Garbellini, A. y Martín-Ramallal, P. (2021). Fake brand gamification. Ludificación de las marcas visuales cómo estrategia de advertainment. AdComunica. Revista Científica de Estrategias, Tendencias e Innovación en Comunicación, 22, 163-188. https://doi.org/10.6035/2174-0992.2021.22.9

Castelló-Martínez, A. (2019). Estado de la planificación estratégica y la figura del planner en España. Los insights como concepto creativo. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 10(2), 29-43. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2019.10.2.7

Castelló-Martínez, A. y Del Pino-Romero, C. (2019). De la publicidad a la comunicación persuasiva integrada: estrategia y empatía. ESIC Editorial.

Cendoya, R. (2018). rEvolución. Del Homo sapiens al Homo digitalis. Sekotia.

Cenizo- Ruiz-Bravo, C. (2022). Análisis de las fashion films de las marcas de lujo del sector moda durante la pandemia del COVID-19. Hipertext. net, 24, 67-81. https://doi.org/10.31009/hipertext.net.2022.i24.06

Corona-Rodríguez, J. M. (2016). ¿Cuándo es transmedia?: discusiones sobre lo transmedia (l) de las narrativas. Revista ICONO 14. Revista científica de Comunicación y Tecnologías emergentes, 14(1), 30-48. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v14i1.919

Cristófol-Rodríguez, C., Villena-Alarcón, E. y Domínguez-García, Á. D. L. C. (2022). Pasarelas de moda, año cero: cambio y percepciones tras la Covid-19. IROCAMM: International Review of Communication and Marketing Mix, 5(1), 72-82. https://doi.org/10.12795/IROCAMM.2021.v05.i01.06

de Aguilera-Moyano, J., Baños-González, M. y Ramírez-Perdiguero, F. (2016). Los mensajes híbridos en el marketing postmoderno: una propuesta de taxonomía. Revista ICONO 14. Revista científica de Comunicación y Tecnologías emergentes, 14(1), 26-57. https://doi.org/10.26754/10.7195/ri14.v14i1.890

de Bono, E. (1991). El pensamiento lateral. Paidós.

del Pino, C. y Castelló, A. (2015). La comunicación publicitaria se pone de moda: branded content y fashion films. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 6(1), 105-128. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2015.6.1.07

EFE (2020). 2020, el año en el que los "fashion films" sustituyeron a los desfiles. La Vanguardia. https://bit.ly/3DjSadq

Fashion Film Festival de Milán [FFF Milano] (2021). Premios Digitales 2021. https://bit.ly/49ndUTS

Fashion Film Festival de Milán [FFF Milano] (2022). Premios Digitales 2022. https://bit.ly/490Zqcu

Fashion Film Festival de Milán [FFF Milano] (2023). – 2023 – Winners & Nominees. https://bit.ly/4bmpQXY

Gibson, J. (2021). Fashion after COVID-19. En L. Li., C. E. Berdud, S. Foster y Stanford, B. (Eds.), Global Pandemic, Technology and Business: Comparative Explorations of Covid-19 and the Law. Routledge.

Hernández-Sampieri, R. (2018). Metodología de la investigación (vol. 4). McGraw-Hill Interamericana.

Isla, P. (2020). Las ventas de Inditex en España cayeron un 41% hasta junio por el coronavirus. Expansión. https://bit.ly/3gYD8lT

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture. Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press.

Jiménez-Marín, G. y Elías-Zambrano, R. (2019). Moda, publicidad y arte. Relación disciplinar a través de las campañas de Moschino y Versace. Prisma Social: revista de investigación social, 24, 25-50. http://hdl.handle.net/10498/21361

Jódar-Marín, J. A. (2019a). La puesta en escena y la postproducción digital del Fashion Film en España (2013-2017). El nuevo formato audiovisual de comunicación en moda concebido para Internet. Revista de la Asociación Española de Investigación de la Comunicación, 6(11), 165-184. https://doi.org/10.24137/raeic.6.11.10

Jódar-Marín, J. Á. (2019b). Caracterización del lenguaje audiovisual de los Fashion Films: Realización y postproducción digital. Revista Prisma Social, 24, 135-152. https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/2825/2979

Kam, L., Robledo-Dioses, K. y Atarama-Rojas, T. (2019). Los fashion films como contenido particular del marketing de moda: un análisis de su naturaleza en el contexto de los mensajes híbridos. Anagramas-Rumbos y sentidos de la comunicación, 17(34), 203-224. https://doi.org/10.22395/angr.v17n34a10

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage publications.

Leung, S. O. (2011). A comparison of psychometric properties and normality in 4-, 5-, 6-, and 11-point Likert scales. Journal of social service research, 37(4), 412-421. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2011.580697

Louis Vuitton. (21 de enero de 2021). Peculiar Contrast, Perfect Light [Archivo de Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vV_QoQD_nrA

Lurie, A. (2013). El lenguaje de la moda. Paidós.

Martín-Ramallal, P. y Merchán-Murillo, A. (2020) De Sixdegress a Facebook Horizon. Las redes sociales hacia el paradigma de la realidad virtual (en tiempos de COVID-19). En F. J. Ruiz-del-Olmo. y J. Bustos-Díaz, Comunicación y consumo mediático en redes sociales y comunidades virtuales, (pp. 121-144). Egregius.

Martín-Ramallal, P. y Ruiz-Mondaza, M. (2022). Agentes protectores del menor y redes sociales. El dilema de TiKToK. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 13(1), 31-49. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM.20776

Martín-Ramallal, P., Bertola-Garbellini, A. y Merchán-Murillo, A. (2019). Blackmirror-Bandersnatch, paradigma de diégesis hipermedia para contenidos mainstream VOD. Ámbitos. Revista Internacional de Comunicación, 45, 280-309. https://doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.2019.i45.16

Méndiz-Noguero, A., Regadera González, E. y Pasillas Salas, G. (2018). Valores y storytelling en los fashion films: El caso Tender Stories (2014-2017), de Tous. Revista de comunicación, 17(2), 316-335. https://doi.org/10.26441/RC17.2-2018-A14

Notario-Rocha, M. L. (2019). Los universos transmedia en la democratización del consumo de lujo en la moda: el caso de Chanel y Karl Lagerfeld. En Experiencias transmedia en el universo mediático (pp. 95-118). Egregius. https://bit.ly/3Kb4FZW

Otzen, T. y Manterola, C. (2017). Técnicas de Muestreo sobre una Población a Estudio. International Journal of Morphology, 35(1), 227-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95022017000100037

Pineda-Cachero, A., Pérez-De Algaba Chicano, C. P. y Hernández-Santaolalla, V. (2013). La ficción como publicidad: Análisis semiótico-narrativo del corporate advertainment. Área Abierta, 34(3), 67-91. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_ARAB.2013.v34.n3.43354

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 2: Do They Really Think Differently? On the Horizon, 9(6), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424843

Sánchez-Mesa Martínez, D. (2019). Narrativas transmediales: La metamorfosis del relato en los nuevos medios digitales. Editorial Gedisa.

Sanz-Marcos, P. y Micaletto-Belda, J. P. (2019). Análisis semiótico de los valores de marca representados en el formato de branded content en los festivales publicitarios españoles. Sphera Pública, 1(19), 47-71. https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/95211

Sartori, G. (2012). Homo videns: la sociedad teledirigida. Taurus.

Velasco-Molpeceres, A. M. (2021). Influencers, storytelling y emociones: marketing digital en el sector de las marcas de moda y el lujo. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2021.154.e1321

Vistelacalle (2021). Fashion films en pandemia: Cuando la historia lo es todo. https://bit.ly/3DosYCf

Viñarás-Abad, M. y Llorente-Barroso, c. (2020). La investigación en publicidad y relaciones públicas: tendencias en contenidos (2000-2020). Index Comunicación. Revista Científica de Comunicación Aplicada, 10(3), 153-180. https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/10/03Lainve

Zhou, J., Tan, J. y Soloaga, P. D. (2022). Reinventando la comunicación en la industria de la moda durante la pandemia COVID-19: el caso LOEWE. aDResearch ESIC International Journal of Communication Research, 27. https://doi.org/10.7263/adresic-27-195

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors' contributions:

Conceptualization: Martín-Ramallal, Pablo and Ruiz-Mondaza, Mercedes Methodology: Martín-Ramallal, Pablo and Ruiz-Mondaza, Mercedes. Formal analysis: Martín-Ramallal, Pablo and Ruiz-Mondaza, Mercedes. Data curation: Martín-Ramallal, Pablo and Ruiz-Mondaza, Mercedes. Drafting and preparation of the original draft: Martín-Ramallal, Pablo and Ruiz-Mondaza, Mercedes. Drafting-Revision and Editing: Martín-Ramallal, Pablo and Ruiz-Mondaza, Mercedes. Supervision: Martín-Ramallal, Pablo and Ruiz-Mondaza, Mercedes. Project management: Martín-Ramallal, Pablo and Ruiz-Mondaza, Mercedes. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: Martín-Ramallal, Pablo and Ruiz-Mondaza, Mercedes.

AUTHORS:

Pablo Martín-Ramallal

University Center San Isidoro, attached to the University Pablo de Olavide.

Associate Professor of the subject of Augmented Reality. He has experience in Social Sciences and Communication at the university level since 2010. Currently, he works as Professor in charge at the University Center San Isidoro, attached to the University Pablo de Olavide. He is an expert in virtual reality, a field where he researches on Communication, Education and Inclusion. He is also an Undergraduate Coordinator and Research Secretary. His research career is intense, having published 22 indexed articles, several as Scopus and JCR. He has written or co-written 30 chapters in SPI indexed journals (Q1 and Q2). He participates in international congresses presenting communications and papers. Martín Ramallal has led 9 teaching innovation projects. He also contributes as a reviewer in journals indexed in Scopus and JCR. Extraordinary Doctorate Award of the Interuniversity Doctoral Program in Communication of the Universities of Cadiz, Seville, Malaga and Huelva, with the research thesis Virtual Reality and Transmedia Advertising. A multidisciplinary study of immersive advergaming.

Índice H: 9

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3055-7312

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=hnJuTdoAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Pablo-Martin-Ramallal-3

Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57208760049

Academia.edu: https://independent.academia.edu/PMart%C3%ADnRamallal

Mercedes Ruiz-Mondaza

School of Higher Artistic Education. Spain.

Graduated with honors in Design by the Higher School of Design CEADE Leonardo. Master in Research Methodology from the International University of La Rioja (UNIR) and also graduated in Audiovisual Communication. Her teaching career spans from 2016 to 2020 in CEADE Leonardo and, since 2020, she serves as Head Professor at the School of Higher Artistic Education of Osuna (ESEA), attached to the University of Seville, space where she is in charge of the Academic Department. Professional linked to the world of Design, Communication and Social Media, she has won awards and recognitions for teaching and social awareness. Her research focuses on Innovation in Education, Communication, Fashion, Design and Information and Communication Technologies, actively participating in the coordination of the Undergraduate in Fashion Design in the academic field.

Índice H: 4

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1385-8626

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=KBOk09UAAAAJ&hl=es

Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57440815800