Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI

|

Received: 11/12/2023 --- Accepted: 21/02/2024 --- Published: 02/04/2024 |

EXPOSURE OF ADOLESCENTS TO FOOD AND BODY CARE INFLUENCER MARKETING

EXPOSICIÓN DE LOS ADOLESCENTES AL MARKETING DE INFLUENCERS SOBRE ALIMENTACIÓN Y CUIDADO CORPORAL

![]() Adela López-Martínez: Universidad Internacional de la Rioja. España. adela.lopez@unir.net

Adela López-Martínez: Universidad Internacional de la Rioja. España. adela.lopez@unir.net

![]() Charo Sádaba: Universidad de Navarra. España.

Charo Sádaba: Universidad de Navarra. España.

csadaba@unav.es

![]() Beatriz Feijoo: Universidad Internacional de la Rioja. España.

Beatriz Feijoo: Universidad Internacional de la Rioja. España.

beatriz.feijoo@unir.net

How to cite this article:

López-Martínez, Adela; Sádaba, Charo, & Feijoo, Beatriz (2024). Exposure of adolescents to food and body care influencer marketing [Exposición de los adolescentes al marketing de influencers sobre alimentación y cuidado corporal]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 57, 1-14. http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2024.57.e863

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Constant exposure to sponsored content by influencers has a direct impact on the eating habits of minors, as well as emotional and self-esteem implications. Methodology: Thus, we aim to understand the type of advertising that teenagers in Spain receive regarding food and body care through influencers by conducting an online survey of 1055 minors aged 11 to 17 years. Results: Nearly 45% of minors confirmed that they receive advertising for unhealthy foods, and although fashion (48.7%) is the sector of body care from which they receive the most promotional inputs, exposure to cosmetic and beauty products (33.1%), fitness and gym products (23.2%), and aesthetic procedures (13.5%) is also notable. Differences based on gender, age, and socioeconomic level were also observed. Discussion: This information reveals that the measures described, such as the PAOS code or self-regulation codes, are not sufficient to reduce minors' exposure to promotion of unhealthy and/or age-inappropriate products. Conclusions: It is essential to continue promoting advertising literacy among minors to enhance their critical thinking skills and enable them to responsibly deal with these commercial messages.

Keywords: influencer marketing; adolescents; food; body care; advertising.

RESUMEN

Introducción: La exposición constante a publicaciones patrocinadas de la mano de los influencers tiene un efecto directo en los hábitos alimenticios de los menores, además de implicaciones emocionales y de autoestima. Metodología: Así, se busca conocer el tipo de publicidad que los adolescentes en España reciben sobre alimentación y cuidado corporal de la mano de influencers mediante la aplicación de una encuesta en línea a 1055 menores de entre 11 y 17 años. Resultados: Casi un 45% de los menores confirmó que recibe publicidad de alimentos poco saludables y, aunque la moda (48,7%) sea el sector del cuidado corporal del que reciben más contenido promocional, destaca la exposición a productos de cosmética y belleza (33,1%), de salud física y gimnasio (23,2%) y a procedimientos estéticos (13,5%). También se observaron diferencias por sexo, edad y nivel socio económico. Discusión: Esta información nos revela que las medidas descritas, como el código PAOS o códigos de autorregulación, no son suficientes para reducir la exposición de menores a promoción de productos poco saludables y/o inadecuados para su edad. Conclusiones: resulta imprescindible seguir fomentando una alfabetización publicitaria en los menores que potencie su capacidad crítica y que les permita enfrentarse a estos mensajes comerciales de forma responsable.

Palabras clave: marketing de influencia; adolescentes; publicidad; alimentación; cuidado del cuerpo.

1. INTRODUCTION

Contemporary Western societies increasingly prioritize healthy eating habits and physical activity for all life stages. Even young children recognize their importance, as shown in the UNICEF Spain Opinion Barometer on Childhood and Adolescence (2021). While Spanish children and adolescents know healthy recommendations, those with lower purchasing power struggle to follow them. The family, school, and media are the primary sources for these recommendations.

The year 2005 saw the introduction of the PAOS code, which aimed to regulate commercial content pertaining to food's impact on adolescents. This co-regulatory agreement sets ethical standards for member companies about the development, execution, and dissemination of their advertising messages. However, in recent times, the focus on ensuring compliance with these standards has shifted towards social media platforms, where minors are known to spend a significant amount of their time. In the realm of advertising, the practice of leveraging influencers has become increasingly widespread. This trend has prompted the development of a set of guidelines for influencer marketing known as the Code of Conduct. This framework was established jointly by Autocontrol and the Spanish Advertisers Association in the year 2021 and seeks to promote ethical and responsible use of influencers in advertising campaigns. This supervision is especially relevant considering some research shows that influencer marketing for minors preferentially features products high in saturated fat, salt, and sugar (HFSS).

This article explores the relationship between Spanish adolescents and the advertising content generated by influencers on food and fitness. It is an original approach to this phenomenon, where traditionally, no attention has been paid to adolescents' opinions. The results may be helpful to reinforce and reformulate the regulation strategies of the advertising sector and, above all, those of the necessary advertising literacy of users in the digital environment.

The aim of this research is to analyze the exposure of minors to influencers’ promotional messages about food and body care products. We also want to detect whether the age, gender or socioeconomic level of adolescents introduce significant differences in exposure to this type of commercial content. To this end, using the quantitative survey method, a sample of teenagers was asked about which food and body care sector they believe they receive the most advertising from influencers. One or more answers could be selected; below, in the methodology section, the response categories are specified.

2. INFLUENCER MARKETING, ADOLESCENTS, FOOD, AND THE CULT OF THE BODY

The amount of time spent by internet users on social networks makes them desirable for commercial brands (IAB Spain, 2023). These platforms offer the possibility of accessing specific demographics and are an essential source of information for consumers during product research (IAB Spain, 2023). To avoid overwhelming users, brands use attractive forms such as games, entertainment, and emotional and social arguments (Feijoo and Sádaba, 2022); in recent years, agreements with influencers have also been added to the mix (Nairn and Fine, 2008; Trivedi and Sama, 2020; Del Moral et al., 2016).

Between 2021 and 2022, the budget invested in influencer marketing in Spain grew by 22.8%, according to official data (Infoadex, 2023). Influencer marketing is when brands compensate users for posting content about their products or services. An influencer is a regular, anonymous user who has gained an audience that trusts their advice thanks to the content they generate (Lou and Yuan, 2019). Even minors admire some of their favorite influencers and consider them part of their close circle, leading them to value their recommendations and believe their advice for purchasing decisions. However, sometimes the content generated by influencers may not differentiate between an authentic recommendation and a commercial recommendation (Zozaya and Sádaba, 2022).

The impact of social media on body satisfaction is well-documented, (Tiggeman and Anderberg, 2020; Lowe-Calverley and Grieve, 2021; Su et al., 2021), particularly among young people (Feijoo et al., 2022). Consuming content on platforms like Instagram has been linked to feelings of unattractiveness: more than 40% of Instagram users acknowledged that the feeling of being unattractive started while using the app (Milmo and Skopeliti, 2021). Some research points out that placing unhealthy foods in influencers' posts increases children's intake of this type of food (Coates et al., 2019). The consequences of this influence are of concern, as constant exposure to this type of content could increase the risk of childhood obesity and have other emotional and self-esteem implications (De Jans et al., 2021; Feijoo et al., 2022).

Likewise, brands use influencers' bodies to communicate an ideal image (Powers and Greenwell, 2016). Appearance matters in social networks, and marketing uses it. Several types of research evidence the role of the body as an advertising appeal in the promoted publications of fitness influencers (Silva et al., 2021).

Minors are exposed to excessive advertising through their cell phones, which are now the primary means of accessing the internet and social media (IAB Spain, 2023). An exploratory study conducted by Feijoo et al. (2020) revealed that children and adolescents spend a significant amount of time on their smartphones using gaming apps and social networks, particularly TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube. These platforms expose users to approximately 14 minutes of advertising per hour of use, which is slightly higher than exposure to advertising on traditional media such as television. Advertising used to occupy over 80% of a child's browsing time, often for unhealthy food, beverages, and sweets on digital and social networks (Alruwaily et al., 2020; Coates et al., 2020; Feijoo et al., 2020; Gascoyne et al., 2021).

A literature review on minors, influencer marketing, eating habits, and body image showed that most studies are from Anglo-Saxon or Western European countries. Studies in the Hispanic context are anecdotal and varied and mainly focused on influencer content analysis, without considering minor's perspectives (Castelló-Martínez and Tur-Viñes, 2021; Tur-Viñes and Castelló-Martínez, 2021; González-Oñate and Martínez-Sánchez, 2020; Feijoo and Fernández-Gómez, 2021; Fernández-Gómez and Díaz Del Campo, 2014). This article offers a novel vision as it provides the perception of adolescents themselves on the reception of advertising content by influencers on social networks, which will provide a basis for establishing recommendations for brands and companies, as well as for educators and families.

3. METHODOLOGY

The data collected for this research is part of a larger-scale project (Feijoo et al., 2023) in which was studied the incidence of influencers on the dietary habits and body care of Spanish teenagers. This is an exploratory research on an emerging phenomenon for which an ad-hoc questionnaire was designed to respond to the specific needs of the study. This is a new instrument, previously validated in a pilot test in which the length of the survey and the wording of some questions were readjusted to the age of the respondents. We designed a questionnaire structured in four blocks: (1) Influence marketing in social networks: the first set of questions seek to determine the type of influencers that minors follow through social networks. (2) Advertising exposure to inputs on food and physical appearance: this set aims to identify the perception minors have on the advertising pressure they are exposed to by the food industry and by body cult followers on social networks and through influencers. (3) Predisposition towards these messages: this set aims to determine the opinion that minors have on influence marketing in the two aforementioned areas and their level of interaction with these contents. (4) Recognition of persuasive intentionality: advertising literacy among minors gauged by the scale designed by Rozendaal et al. (2016), ALS-C (Advertising Literacy Scale for children) which was tested on children.

We enlisted 1,055 individuals aged between 11 and 17 years old from a from a Spanish online user panel. The selection criterion was that they were social network users. The participants were subjected to self-administered online surveys using the platform Survio.com; they were selected through a meticulous process of proportional stratified random sampling, ensuring a 95% confidence level, a +/-3% margin of error, and maximum variance consideration. The sampling approach adopted a multi-stage design, looking for a better representation of our objective population, with the first stratum focusing on geographical areas and a second level of stratification based on the socioeconomic status of families (categorized as low, medium, and high). The final selection of survey participants followed cross-quota criteria related to gender and age. The fieldwork spanned from April to June 2022.

This paper focuses on the second block of the questionnaire. Table 1 describes the specific variables taken into consideration in this study to respond to the research objective. A descriptive analysis of the critical study variables is presented, such as (a) exposure to food/body care advertising in digital media; (b) food sector by which it receives more advertising from the hand of influencers; (c) body care sector by which it receives more advertising from the hand of influencers. Finally, a bivariate analysis took the demographic variables (age, gender, and SES) as a reference to establish the degree of association between the two variables and identify and understand the differences between the different population groups.

To determine the statistical significance of the differences observed in the responses in these crosstabs, the test of independence based on Pearson's Chi-square statistic was used to assess the degree of association between two nominal variables. In all cases, it was established that the p-value to reject the null hypothesis of the tests performed would be <0.05. When this is the case, the differences will be reported as significant. This will be marked in the text or with an asterisk (*) in tables and/or figures.

Table 1.

Description of analysis variables.

|

Variable |

Values |

Type |

|

Gender |

Man Woman |

Binary |

|

Age |

|

Ordinal |

|

Socioeconomic status |

High SES Middle SES Low SES |

Ordinal |

|

How often do you receive food or body care advertising in the following digital media? Websites Search engines such as Google YouTube TikTok Twitch Games Discord Spotify |

I do not use this platform Infrequent Somewhat frequent Frequent Very frequent |

Ordinal |

|

About which food sector do you think you receive the most advertising from influencers? |

Healthy foods Half-healthy foods Unhealthy foods I do not receive or am not aware of receiving advertising of these products |

Nominal |

|

About which body care sector do you think you receive the most advertising from influencers? |

Fashion Cosmetics, beauty... Aesthetic procedures Fitness and gyms Communication and events I do not receive or am not aware of receiving advertising of these products |

Nominal |

Source: Own resource.

The distribution of the sample was as follows: by age, 13.9% students aged 11, 14.4% aged 12, 14.5% aged 13, 15.4% aged 14, 14.1% aged 15, 14.1% aged 16 and 13.6% aged 17; by gender, 54% were male, 46% female. In terms of socioeconomic level: 30.2% low level, 50.4% medium level, and 19.3% high level.

The nature of this project implies a series of ethical considerations, particularly due to the participation of minors in the fieldwork. For this reason, the researchers got the express parental authorization expressed in a consent document, previously validated by the Ethics Committee of the university which holds this project (Universidad Internacional de la Rioja). Likewise, the same ethics committee supervised the project to be in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (review of Fortaleza - Brazil, October 2013).

4. RESULTS

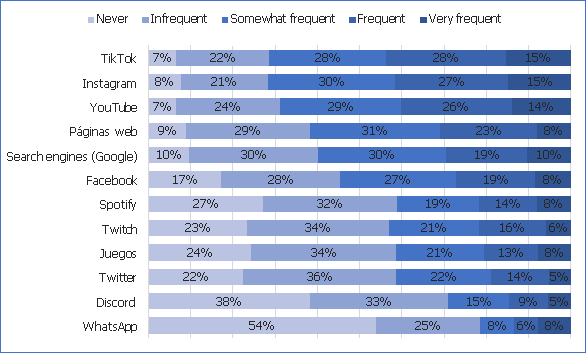

According to the people surveyed, TikTok and Instagram are the digital platforms that broadcast more advertising about products and services linked to the food or body care sector (Figure 1). Other more widespread applications, such as YouTube, search engines, or web pages, would have a slightly lower diffusion of these contents. Others, such as Spotify, Twitch, or Twitter, are placed one position behind, while on Discord or WhatsApp, it would be rare to see publications of this type.

Figure 1

Frequency of receiving food or body care advertising on different platforms.

Source: Own resource

The frequency with which adolescents report receiving advertising on these platforms has no significant differences in age or SES. Regarding gender, only in the case of the Instagram platform do females report receiving significantly more advertising than males [Never= M(9.9%) vs F(5.2%); Infrequent= M(22.7%) vs F(18.6%); Somewhat frequent= M(30.7%) vs F(29.6%); Frequent= M(24.0%) vs F(29.6%); Very frequent= M(12.8%) vs F(17.0%)].

However, the types of advertising that adolescents receive in these media from influencers are various and of very different typologies. In this study, the following has been determined:

- Children receive more advertising, almost twice as much, about unhealthy foods than foods they consider healthy (Table 2).

- Only 14.4% say they do not receive advertising about food products through influencers, and 11.9% do not receive about body care.

- Nearly half of young people (48.7%) receive commercial inputs about fashion from these content creators (Table 3).

- Promotions about body image are very present in adolescents' daily lives: one in three receives advertising about cosmetics and beauty from influencers, and 13.5% have even seen persuasive publications referring to aesthetic procedures.

Although the frequency with which adolescents are exposed to food and body care advertising through influencers is quite similar, especially in terms of gender and SES, are there differences in the type of commercial messages presented to them by these media figures?

Regarding food advertising, the answer is that there are no significant differences applying the chi square test, either by age, gender, or SES (Table 2). Despite this lack of statistical robustness to support the conclusions and allow extrapolation of these data to the population, it is true that in the sample collected, women have tended to report more impression of food advertising, although, as indicated, in marginal and non-significant percentage differences.

Table 2

Differences in exposure to different types of food advertising by gender and SES.

|

|

Man |

Woman |

High SES |

Medium SES |

Low Ses |

Total |

|

Healthy food |

23.1% |

24.6% |

23.5% |

23.9% |

23.8% |

44.5% |

|

Medium-healthy foods |

15.7% |

18.4% |

17.2% |

15.8% |

18.8% |

23.8% |

|

Unhealthy foods |

43.6% |

45.5% |

46.6% |

45.7% |

41.4% |

17.0% |

|

I do not receive or am not aware of receiving advertising of these products |

16.1% |

12.5% |

14.7% |

16.2% |

11.3% |

14.4% |

Source: Own resource.

On the other hand, although not significant, children from low SES households report a lower reception of advertising content about unhealthy foods. This could be because the ability to differentiate or define food quality differs between high and low-SES families.

However, the differences become noticeable when analyzing the advertising types about the body and its care (Table 3). In terms of gender, we see a massive variance in advertising about cosmetics, aesthetic procedures, and fitness. It can be affirmed that this structure reproduces (or reinforces) traditional gender stereotypes, focusing on strengthening and bodybuilding for men and beauty through makeup or surgery for women.

Table 3

Differences in exposure to body care advertising by gender and SES.

|

|

Man |

Woman |

High SES |

Middle SES |

Low SES |

TOTAL |

|

Fashion |

45.9% |

51.8% |

52.0% |

47.0% |

49.5% |

48.7% |

|

Cosmetics, beauty... |

18.0%* |

50.6%* |

35.8% |

33.8% |

30.1% |

33.1% |

|

Aesthetic procedures |

9.4%* |

18.2%* |

19.1%* |

13.7%* |

9.4%* |

13.5% |

|

Fitness and gyms |

29.0%* |

16.6%* |

25.5% |

23.3% |

21.6% |

23.1% |

|

Communication and events |

6.2% |

4.5% |

7.4% |

5.8% |

3.4% |

5.4% |

|

I do not receive or am not aware of receiving advertising of these products |

14.1% |

9.4% |

6.4% |

13.5% |

12.9% |

11.9% |

Source: Own resource.

The differences in terms of SES are less and only noticeable in the case of aesthetic procedures: they are more common among the population living in households with a higher SES, either because these are the same adolescents who seek more information about this or because the platforms have enough information to be able to send these publications to people with a better economic position or predisposition to be able to carry them out.

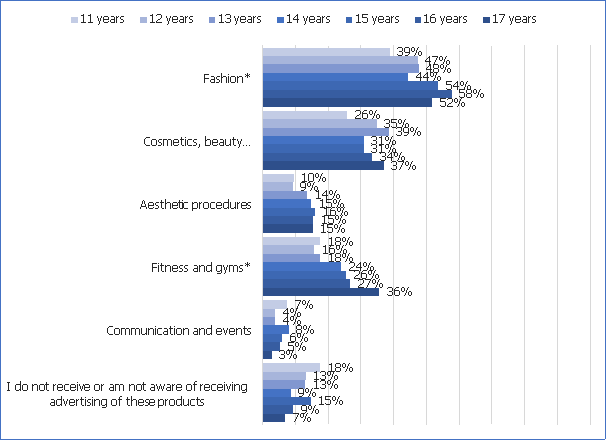

The age structure shows a significant increase in commercial messages referring to fashion and fitness/gym among the more mature age groups (Figure 2). However, the differences are as striking as the lack of them. For example, the proportion of 17-year-olds receiving advertising for aesthetic procedures is only 6% higher than 11-year-olds and only 2% higher than 13-year-olds.

Figure 2

Age differences in exposure to body care advertising.

Source: Own resource.

5. DISCUSSION

Social networks, especially TikTok and Instagram, are the digital platforms where adolescents perceive that they receive more commercial inputs about food and body care from influencers. These are the most used virtual environments by this age group (IAB Spain, 2023). The fact that there are hardly any significant differences in advertising exposure demonstrates the uniformity of exposure to influencer marketing among the sample used, except Instagram, which tends to be a platform more akin to the female audience.

Almost half of the adolescents surveyed confirmed that they preferentially receive promotional inputs of unhealthy products, a particularly worrying fact when it has been shown that exposure to this type of content increases the consumption of this type of food (Coates et al., 2019). Therefore, it becomes necessary to make children aware of the health consequences of this diet, significantly when their decision-making power in household purchases is increasing.

As for the exposure to commercial messages about products related to physical appearance, although it is not surprising that the fashion sector is the most mentioned by adolescents, it is disturbing that products directly related to the cult of the body, such as makeup, fitness, gyms, and esthetic procedures, are so present in the lives of adolescents and at such an early age. Indeed, statistics show that almost 10% of 11-year-old boys and girls receive advertising on aesthetic issues, with similar percentages among 17-year-olds (15.4%). Similarly, the penetration of the world of cosmetics, fitness, and gyms among young people is noteworthy, which shows how these brands are increasingly trying to attract consumers at younger ages, introducing adolescents to types of consumption previously reserved for adults.

These results are especially relevant because they provide specific data on what promotional inputs adolescents retain about food and body care in the digital context and by influencers. This information reveals that the measures described, such as the PAOS code or self-regulatory codes, are not sufficient to reduce the exposure of teens to the promotion of unhealthy and/or inappropriate products for their age, so there is a clear need for brands, advertisers and influencers to assume a more significant commitment to the broadcast of this type of persuasive content, in addition to signaling it as such (Zozaya and Sádaba, 2022). In this context, it is also essential to continue promoting advertising literacy among minors to enhance their critical capacity and enable them to deal with these commercial messages responsibly.

This research developed in Spain can be replicated in other Spanish-speaking countries to compare the results of advertising exposure of children from different countries who follow the same influencers. Steps are already being taken to carry out this study in countries such as Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico.

6. CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that children are the audience for products and services previously reserved for adults. In addition, these are sectors - food and body care - with direct implications on the physical and mental health of consumers, especially among the young target. Moreover, we must add to the equation the incidence of influencers, perceived not so much as content generators, but as close friends whose opinions or recommendations are sincere and disinterested.

For this reason, it is important that the public health field continues to stress the importance of paying particular attention to the use of influencer marketing strategies when the target audience is underage. Fundamentally because this may imply that minors have a lower critical capacity to understand the implications of the parasocial relationships they create with influencers.

This study has some limitations that should be considered, particularly those related to the methodology employed. The findings presented here are based on self-reported intentions from a sample of Spanish adolescents; further investigation is needed to determine if these intentions align with their actual perceptions and concerns regarding this issue. A more qualitative study design would be beneficial in addressing these limitations.

7. REFERENCES

Alruwaily, A., Mangold, C., Greene, T., Arshonsky, J., Cassidy, O., Pomeranz, J. L., & Bragg, M. (2020). Child social media influencers and unhealthy food product placement. Pediatrics, 146(5). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-4057

Castelló-Martínez, A., & Tur-Vines, V. (2021). Una combinación de alto riesgo: obesidad, marcas de alimentación, menores y retos en YouTube. Gaceta Sanitaria, 35(4), 352-354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2020.06.018

Coates, A. E., Hardman, C. A., Halford, J. C. G., Christiansen, P., & Boyland, E. J. (2020). It’s just addictive people that make addictive videos: Children’s understanding of and attitudes towards influencer marketing of food and beverages by YouTube video bloggers. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(2), 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020449

Coates, A. E., Hardman, C. A., Halford, J. C. G., Christiansen, P., & Boyland, E. J. (2019). The effect of influencer marketing of food and a “protective” advertising disclosure on children's food intake. Pediatric obesity, 14(10), e12540. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12540

De Jans, S., Spielvogel, I., Naderer, B., & Hudders, L. (2021). Digital food marketing to children: How an influencer's lifestyle can stimulate healthy food choices among children. Appetite, 162, 105182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105182

Del Moral, M. E., Villalustre, L., & Neira, M. R. (2016). Estrategias publicitarias para jóvenes: advergaming, redes sociales y realidad aumentada. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 7(1), 47-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2016.7.1.3

Feijoo, B., & Fernández-Gómez, E. (2021). Niños y niñas influyentes en YouTube e Instagram: contenidos y presencia de marcas durante el confinamiento. Cuadernos.Info, 49, 302-330. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.49.27309

Feijoo, B., López-Martínez, A., & Núñez-Gómez, P. (2022). Body and diet as sales pitches: Spanish teenagers’ perceptions about influencers’ impact on ideal physical appearance. El Profesional de la Información, 31(4). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.jul.12

Feijoo, B., & Sádaba, C. (2022). When mobile advertising is interesting: interaction of minors with ads and influencers’ sponsored content on social media. Communication & Society, 35(3), 15-31. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.35.3.15-31

Feijoo, B., Sádaba, C., & Bugueño, S. (2020). Anuncios entre vídeos, juegos y fotos. Impacto publicitario que recibe el menor a través del teléfono móvil. El Profesional de la Información, 29(6). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.nov.30

Feijoo, B., Zozaya, L., Cambronero-Saiz, B., Mayagoitia, A., González, J. M., Sádaba, C., Núñez, P., & Miguel, B. (2023). Digital fit: Influencia de las redes sociales en la alimentación y en el aspecto físico de los menores. [Social media influence on diet and physical appearance of minors]. Fundación Mapfre.

Fernández-Gómez, E., & Díaz-Campo, J. (2014). La publicidad de alimentos en la televisión infantil en España: promoción de hábitos de vida saludables. Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, 8(4), 133-150. https://www.doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS842014802

Gascoyne, C., Scully, M., Wakefield, M., & Morley, B. (2021). Food and drink marketing on social media and dietary intake in Australian adolescents: Findings from a cross-sectional survey. Appetite, 105431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105431

González-Oñate, C., & Martínez-Sánchez, A. (2020). Estrategia y comunicación en redes sociales: Un estudio sobre la influencia del movimiento RealFooding. Ámbitos. Revista Internacional de Comunicación, 48, 79-101. https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.2020.i48.05

IAB Spain (2023). Estudio de redes sociales 2023. https://acortar.link/k0kSrr

Infoadex (2023). Resumen Estudio Infoadex de la Inversión Publicitaria en España 2022. https://acortar.link/7Hs9Tb

Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: how message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501

Lowe-Calverley, E., & Grieve, R. (2021). Do the metrics matter? An experimental investigation of Instagram influencer effects on mood and body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 36, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.10.003

Milmo, D., & Skopeliti, C. (2021). Teenage girls, body image and Instagram’s ‘perfect storm’. The Guardian. https://acortar.link/kkiOau

Nairn, A., & Fine, C. (2008). Who’s messing with my mind? The implications of dual-process models for the ethics of advertising to children. International Journal of Advertising, 27(3), 447-470. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0265048708080062

Powers, D., & Greenwell, DM. (2016). Branded fitness: Exercise and promotional culture. Journal of Consumer Culture, 17(3), 523-541. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540515623606

Rozendaal, E., Opree, S. J., & Buijzen, M. (2016). Development and validation of a survey instrument to measure children's advertising literacy. Media Psychology, 19(1), 72-100. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2014.885843

Silva, M. D. B., Farias, S. A., Grigg, M. H., & Barbosa, M. L. (2021). The body as a brand in social media: analyzing digital fitness influencers as product endorsers. Athenea Digital, 21(1), 1-34. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/athenea.2614

Su, Y., Kunkel, T., & Ye, N. (2021). When abs do not sell: The impact of male influencers conspicuously displaying a muscular body on female followers. Psychology & Marketing, 38(2), 286-297. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21322

Tiggemann, M., & Anderberg, I. (2020). Muscles and bare chests on Instagram: The effect of Influencers’ fashion and fitspiration images on men’s body image. Body Image, 35, 237-244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.10.001

Trivedi, J., & Sama, R. (2020). The effect of influencer marketing on consumers’ brand admiration and online purchase intentions: An emerging market perspective. Journal of Internet Commerce, 19(1), 103-124. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2019.1700741

Tur-Viñes, V., & Castelló-Martínez, A. (2021). Food brands, YouTube and Children: Media practices in the context of the PAOS self-regulation code. Communication & Society, 34(2), 87-105. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.34.2.87-105

Unicef (2021). ¿Qué opinan los niños, niñas y adolescentes? Resultados de la segunda edición del Barómetro de Opinión de Infancia y Adolescencia 2020-2021. https://acortar.link/BYt3NL

Zozaya, L., & Sádaba, C. (2022). Disguising Commercial Intentions: Sponsorship Disclosure Practices of Mexican Instamoms. Media and Communication, 10(1), 124-135. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i1.4640

CONTRIBUCIONES DE AUTORES, FINANCIACIÓN Y AGRADECIMIENTOS

Contribuciones de los autores:

Conceptualización: López-Martínez, Adela, Sádaba, Charo. Metodología: Feijoo, Beatriz. Software: Feijoo, Beatriz. Validación: Feijoo, Beatriz. Análisis formal: Feijoo, Beatriz. Curación de datos: Feijoo, Beatriz. Redacción-Preparación del borrador original: López-Martínez, Adela, Sádaba, Charo. Redacción-Revisión y Edición: López-Martínez, Adela, Sádaba, Charo. Visualización: López-Martínez, Adela, Sádaba, Charo. Supervisión: López-Martínez, Adela. Administración de proyectos: Feijoo, Beatriz. Todos los autores han leído y aceptado la versión publicada del manuscrito: López-Martínez, Adela, Sádaba, Charo, Feijoo, Beatriz.

Financiación: Esta investigación recibió financiamiento externo de la Fundación Mapfre.

AUTOR/ES:

Adela López-Martínez

Universidad Internacional de la Rioja.

Vice Rector of Students at UNIR. With D. in Italy, she has developed her university activity at the University of Los Andes, in Santiago de Chile (2007-2019). She has a teaching and university management profile. She has taught many courses in Anthropology, Ethics and Philosophy of Education in the Faculties of Philosophy and Education and in the Center for General Studies at the University of Los Andes. She has directed final degree dissertations. In 2016 she was awarded the Best Academic Advisor Award of the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Los Andes.

Índice H: 2

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3428-4868

Charo Sádaba

Universidad de Navarra.

Full professor of advertising and marketing at the School of Communication, University of Navarra (Spain). Her research has been focused on the impact of digitalization on children and teenagers, their behavior, attitudes and opinions towards technology, particularly in Spain and Latin American countries. More recently she has started a project on the impact of technology in emerging adulthood.

Índice H: 30

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2596-2794

Beatriz Feijoo

Universidad Internacional de la Rioja.

Associate professor of advertising and marketing at the School of Business and Communication, International University of La Rioja (Spain). Her research focuses on communication and children, the use of screens in new generations, and more recently on the relationship between minors and advertising through the mobile devices. She is also the principal investigator of funded research projects (Fondecyt N°11170336—Chile; I+D+i Project—Spain ref. PID2020‐116841RAI00; PENSACRIGITAL‐UNIR) on communication, new media, childhood, and adolescence.

Índice H: 14

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5287-3813