https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2020.53.103-134

INVESTIGACIÓN

COMMUNICATION FROM THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY ON READABILITY IN SPANISH LANGUAGE ON SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING

LA COMUNICACIÓN DESDE EL CONSEJO DE ADMINISTRACIÓN: ESTUDIO EMPÍRICO SOBRE LA LEGIBILIDAD DE LOS INFORMES DE SOSTENIBILIDAD EN ESPAÑOL

A COMUNICAÇÃO DO CONSELHO DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO: ESTUDO EMPÍRICO SOBRE A LEGIBILIDADE DOS INFORMES DE SUSTENTABILIDADE EM ESPANHOL

Mónica Cervantes Sintas1

1Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. Spain.

ABSTRACT

This article analyses the readability of the communication in Spanish language from the board of directors based on the study of narrative texts at Sustainability Reports of IBEX35 companies, which includes the 35 largest listed companies in Spain given their market capitalization. It undertakes an empirical study with two purposes: first, to describe the readability scale of these texts, and second, to ascertain whether or not compliance on sustainability influences the readability of disclosure. The study was carried out on the narrative texts of six GRI data standards related to compliance with laws and regulations, included in 116 Sustainability Reports of IBEX35 Spanish-listed companies in the period 2015-2018. Readability was measured using two indices for Spanish language readability: the Fernandez-Huerta and the Inflesz indices. These indices are based on the Flesch Reading Ease Formula for English narrative texts. Findings suggest that communication from the board concerning Sustainability Reports needs improvement since, in general, these reports are difficult to read. Finding also suggest that compliance with GRI standards could be related to low readability difficulty of reports and non-compliance to high readability difficulty.

KEY WORDS: board communication, readability, sustainability report, csr, stakeholders, corporate governance.

RESUMEN

Este artículo analiza la legibilidad de la comunicación en idioma español por parte del consejo de administración basada en el estudio de textos narrativos de los informes de sostenibilidad de las empresas del IBEX35, que incluye a las 35 empresas más grandes en España según su capitalización de mercado. Este estudio empírico tiene dos propósitos: primero, identificar la escala de legibilidad de estos textos, y segundo, determinar si el cumplimiento de los criterios de sostenibilidad influye o no en la legibilidad de su comunicación. El estudio se ha llevado a cabo sobre los textos narrativos de seis estándares de datos GRI relacionados con el cumplimiento de las leyes y reglamentos, incluidos en 116 Informes de sostenibilidad de las empresas con cotización española IBEX35 en el período 2015-2018. La legibilidad se midió utilizando dos índices en español: los índices Fernández-Huerta e Inflesz. Estos índices se basan en la “Flesch Reading Ease Formula” para textos narrativos en inglés. Los resultados sugieren que la comunicación del consejo de administración con respecto a los informes de sostenibilidad necesita una mejora ya que, en general, estos informes son difíciles de leer. Los resultados también sugieren que el cumplimiento de los estándares GRI podría estar relacionado con alta legibilidad y el incumplimiento con baja legibilidad.

PALABRAS CLAVE: comunicación, consejo, legibilidad, informe sostenibilidad, rsc, stakeholders, gobierno corporativo.

RESUMO

Este artigo analisa a legibilidade da comunicação no idioma espanhol pelo conselho de administração baseada no estudo de textos narrativos dos informes de sustentabilidade das empresas do IBEX35, que inclui as 35 maiores empresas na espanha segundo sua capitalização de mercado. Este estudo empírico tem dois propósitos: primeiro, identificar a escala de legibilidade desses textos, e segundo, determinar se o cumprimento dos critérios de sustentabilidade influi ou não na legibilidade da comunicação. O estudo foi realizado sobre os textos narrativos de seis padrões de dados GRI relacionados com o cumprimento das leis e regulamentos, inclusos em 116 Informes de sustentabilidade das empresas com cotação espanhola no IBEX35 no período 2015-2018. A legibilidade foi medida usando dois índices em espanhol: os índices Fernández-Huerta e Inflesz. Estes índices estão baseados na “Flesch Reading Ease Formula” para textos narrativos em inglês. Os resultados sugerem que a comunicação do conselho de administração em relação aos informes de sustentabilidade precisa de uma melhora já que, em geral, esses informes são difíceis de ler. Os resultados também sugerem que o cumprimento dos padrões GRI poderia estar relacionado com alta legibilidade e o incumprimento com baixa legibilidade.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Comunicação, Conselho, Legibilidade, Informe sustentabilidade, RSC, stakeholders, governo corporativo.

Correspndence:

Mónica Cervantes Sintas: Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. Spain. m.cervantes@alumnos.urjc.es

Received: 28/04/2020.

Accepted: 30/07/2020.

Published: 15/11/2020.

How to cite the article:

Cervantes Sintas, M. (2020). Communication from the board of directors: An empirical study on readability in Spanish language on Sustainability Reporting. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 53, 103-134. doi: https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2020.53.103-134

Recuperado de http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/641

1. INTRODUCTION

The external community and capital markets, where we can find individual shareholders, institutional investors, governments, local communities, clients, employees and suppliers, among others, have become greatly interested in sustainability issues in recent years (Arena, Saverio & Giovanna, 2015; Boiral, Heras-Saizarbitoria & Testa, 2017; Cormier and Magnan, 2013; Dhaliwal, Li, Tsang, 2011; Escrig-Olmedo, Muñoz-Torres, & Fernández Izquierdo, 2013; Hill, Ainscough, Shank, & Manullang, 2007; Reverte, 2012). In fact, there has been an increase in investments under ethical and socially responsible criteria (Clarkson, Richardson & Vasvari, 2008). Consequently, companies have increased sustainability reported information because of the business interests and moral responsibility they recognize in this practice (Adams and Zutshi 2004; Amran, Ping Lee and Devi, 2014; Crowther, 2000) and are becoming aware that Sustainability Reports should represent the interests of all their stakeholders (Sacconi, 2004; Smeuninx, Clerck & Aerts, 2016).

In the communication between companies and stakeholders, sustainability reporting is an important tool that contributes to engagement with stakeholders and attends to their demands for more information on sustainability policies, strategies, performance and impacts (ACCA & NetBalance, 2007; Gray, Kouhy & Lavers, 1995; Hahn & Kühnen, 2013; Marín, Rubio & Ruiz de Maya, 2012), as well as on transparency and effective governance (Amran et al., 2014; Lungu, Caraiani & Dasc?lu, 2011; Subramaniam, Hodge, & Ratnatunga, 2006). It also provides investors with information about the company on ecological, economic and social data (Clarkson et al., 2008), and, furthermore it increases accountability to stakeholders, instead of being a purely public relations tool (Boiral et al., 2017; Cho, Michelon & Pattern, 2012; Fonseca, McAllister & Fitzpatrick, 2014; Hahn and Kühnen, 2013; Junior, Best & Cotter, 2014; Perego and Kolk, 2012). Sustainability Reporting appeals to a wider audience than financial or corporate governance reporting (see, for example, GRI, 2013; Smeuninx et al, 2016), being of interest to stakeholders in the wider sense of the concept of stakeholders, which, as such theory stands, would include those who could be positively or negatively affected by corporate operations, even if they don’t participate directly in them (Sacconi, 2004; Smeuninx et al., 2016). Studies have confirmed an increase in environmental and social performance reporting (Morhardt, Baird & Freeman, 2002; O’Dwyer & Owen, 2005), which is becoming a mainstream global business practice (Kolk, 2010; Van Wensen, Broer, Klein & Knopf, 2011). In 2017, The Governance and Accountability Institute indicated that more than 82% of S&P 500 companies had published a Sustainability Report, whereas only 53% S&P 500 companies published one in 2012 (Pei-yi Yu, Qian Gou & Van Luu, 2018). In 2017, KPMG’s Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting signified that 78% of companies issuing reports worldwide had included corporate responsibility information in their annual financial reporting. In 2011, that figure was a 44%. There is, however, some confusion over how to name these reports. Amran et al. (2014) states that “[the term] ‘Sustainability report’ is used interchangeably with various reporting methods such as corporate responsibility reporting, social and environment reporting, etc. (Brundtland & Khalid, 1987).” (p. 218 footnote) The content of the report is based on the concept of sustainable development, which implies preserving resources for present and future generations (Amran et al., 2014).

If we look at the Townsend, Bartels & Renaut (2010) Readers and Reporters of Sustainability Reporting Survey, we find that the main motivation of readers of Sustainability Reports is “informing decisions on use of the organization’s products/services,” closely followed by “informing investment/ divestment decisions” (Smeuninx et al., 2016, p. 60). Findings in the survey emphasize that, although the average reader reads three reports, the top 5% reads between 10 and 20 reports per year; it’s important to underline that most readers in the sample are nonexpert (Smeuninx et al., 2016). Another fact to emphasize from Townsend et al. (2010) is that the audience for reports has become more diverse, being 48% company-internal, 16% investors, 14% company-external value chain, and 22% “`Civil Society,’ entailing media, labor unions, public institutions, academics and other experts, and concerned citizens and consumers” (Smeuninx et al., 2016, p. 60). Due to this diversity, it would be reasonable for companies to adapt their communication to these new receptors by improving the narrative texts’ readability, among others (Smeuninx et al., 2016).

Moreover, corporate governance is undergoing a change that is widening its scope and now covers issues of concern on environmental, social and public matters (McBarnet, 2007), as well as “issues related to ethics, accountability, and disclosure (Lerach, 2002)” (Kaymak & Bektas, 2017, p. 556). This was foreseen in some CG definitions that introduced the concept of stakeholders, such as OECD´s (2015, p. 9), which suggests that “Corporate governance involves a set of relationships between a company’s management, its board, its shareholders and other stakeholders.” Accordingly, traditional sustainability issues such as non-financial reporting practices, codes of conduct, stakeholder engagement, etc., are now being addressed by CG practices (Rahim & Alam, 2013; Kaymak & Bektas, 2017).

Harris & Hodges, (1995) declare that readability refers to the ease of reading and understanding a written text. This paper will adopt the statement from Smeuninx et al. (2016) that “when a text’s features make it easier for the reader to extract desired information it is more readable” (p. 55). Readability can be a powerful communication tool used by some companies to manipulate the understanding of the disclosed information on their interest, making the narrative more readable when the information given is positive, and doing otherwise when negative (Wang, Hsiech & Sarkis, 2018). So, determining the readability difficulty level of sustainability narrative texts in Spanish, as well as whether or not compliance on sustainability information is influenced by readability, will be explored in this paper. This study was done on 116 Sustainability Reports of IBEX35 Spanish-listed companies in the period 2015-2018. The IBEX35 index unites the 35 largest listed companies in Spain given their market capitalization. According to stakeholder theory, company size is linked to sustainability disclosures (Baumann-Pauly, Wickert, Spence & Scherer, 2013; Boesso and Kumar, 2007; Li, 2008; Neu, Warsame & Pedwell, 1998; Roberts, 1992; Tagesson, Blank & Broberg, 2009; Tamimi & Sebastianelli, 2017). For this research, we manually collected the GRI data related to compliance with laws and regulation on anti-corruption, anti-competitive behavior, environmental compliance, labeling, marketing and socioeconomic compliance, and classified it following KLD database criteria. Then the Fernandez Huertas and the Inflesz Spanish readability indices were applied. Results show the rating on the readability of sustainability narrative texts was “high” for both indices, which means the texts are difficult to read. Other results, obtained by applying multiple regressions, suggest an association between compliance and readability.

As far as we know, this is the first study to consider the readability of sustainability activities through the Sustainability Report and relates it to compliance with GRI standards. Moreover, it adds evidence to the scant literature concerning readability in the Spanish language.

This paper is organized as follows. There is a review of relevant literature, as well as a theoretical framework containing the questions and hypotheses of this study. Then the methodology is described, which includes reference to the readability indices used. Lastly, there is the discussion, conclusions to be drawn from the study, and recommendations.

2. OBJECTIVES

This paper’s objective is twofold. First, to ascertain the rating of Sustainability Reports’ narrative texts on the readability scale, and second, to consider whether compliance on sustainability standards influences the readability of disclosure.

3. LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

3.1. Literature review on the communication of Sustainability Reports and Readability

This study began with a review of the articles the academic community had provided on terms related to the purpose of this study.

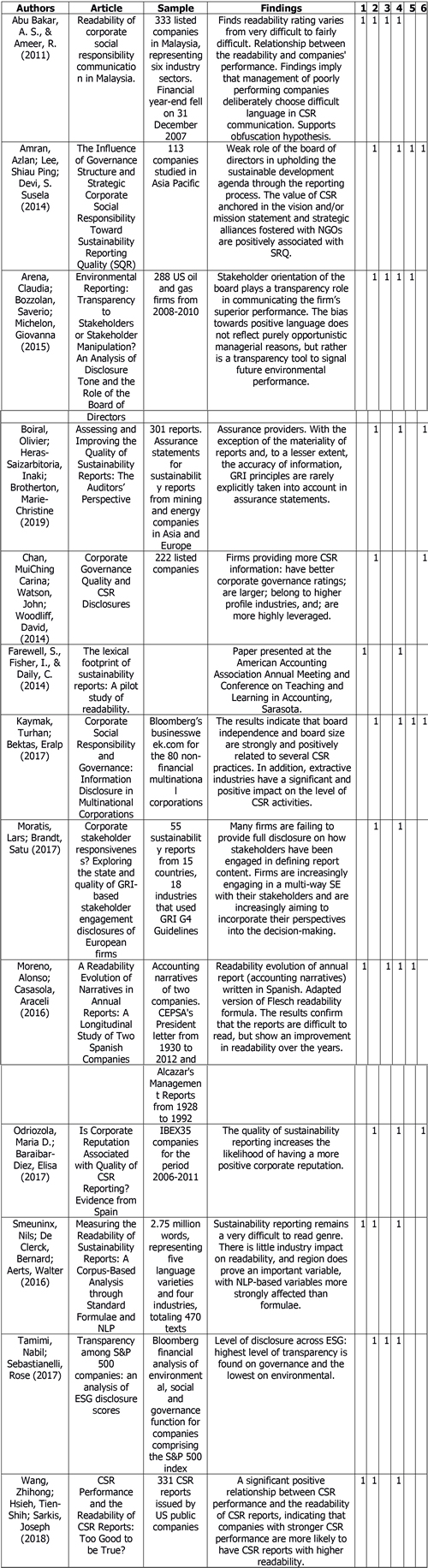

Table 1 presents the results of the literature review on articles related to communication readability on Sustainability Reports, with a special focus on the Spanish language. The results were obtained using WOS, Web of Science. The terms listed below were searched for using the “key words” and “title” article fields, from a date range of 1900 to December 2019, in social science and juridical magazines with content on management, business and communication. Following completion of the research, a manual review was done, looking for those articles that were closer to the research topic and giving priority to articles that studied communication, as well as reporting. The next step was to dismiss those articles that were repeated in the researches, and this left us with 64 unique articles. Among those 64 articles, the ones that were even closer to our study gap, because they specifically studied reporting on sustainability or readability or both, were identified, bringing the number of articles down to 36. The research terms and the number of articles found and selected were as follows (number of articles found/number of articles selected): readability & reports (38/4); readability & reports & Spanish (3/1); formal & communication & investors (9/0); formal & disclosure & investors (16/0); sustainability & reporting (721/22); sustainability & disclosure (359/11); accessibility & sustainability (16/0); accessibility & disclosure (14/0); access & GRI & information (3/0); transparency & sustainability (118/26).

Table 1 shows articles related to communication readability on Sustainability Reports, with a special interest on the Spanish language.

Table 1. A communication readability review on sustainability reports.

Source: by author.

Articles have been classified based on the main issues they cover, which include the following: (1) Readability, (2) CSR/Sustainability, (3) Communication; (4) Reporting; (5) Corporate Governance; (6) Reporting Quality. The studies carried out by the academic community between 1900 and December 2019 have focused much on CSR/ Sustainability (11 studies) and reporting (12 studies). Additionally, 4 of them focused on communication, 4 of them on Sustainability and Corporate Governance, and 5 on reporting quality. Only 5 articles have studied the readability of the information provided, and only one of those focused on reports written in the Spanish language. Based on this information, we came to the conclusion that there is a clear research gap that we aim to fill with this study.

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been done on the readability of sustainability reporting narrative texts in the Spanish language. Moreno and Casasola (2016) have studied the readability of Spanish accounting narrative reports, but over only two companies. In the English language, we find four studies. Smeuninx et al. (2016) suggests sustainable reporting is a very difficult-to-read genre, sometimes being even more difficult than financial reporting. Farewell, Fisher, and Daily (2014) concluded that reports had a low readability and would be difficult to read for stakeholders, and encouraged companies to simplify their language. Abu Bakar and Ameer (2011) found that CSR reporting of Malaysian companies was highly difficult to read and that it got even more difficult as company performance deteriorated (Smeuninx et al., 2016). Wang et all (2018) found a significant positive relationship between CSR performance and the readability of CSR reports.

There are different studies on the concept of readability (e.g., DuBay, 2004; Klare, 1963; McLaughlin, 1969), or readability vs understandability (Conversely, Smith and Taffler, 1992), since readability can be a powerful communication tool, used by some companies to manipulate the understanding of the disclosed information in their interest, making narrative more readable when the information given is positive and doing otherwise when negative (Kaymak & Bektas, 2017; Wang et al., 2018). This is what some scholars call “obfuscation hypothesis” (Courtis, 1998; Rutherford, 2003; Smeuninx et all, 2016). For example, studies by Adelberg (1979) and Li (2008) have suggested that readability of company reports and financial performance were negatively associated (Wang et al. 2018); “Cho, Michelon, and Patten (2012) found that sustainability reports, just like financial reports, show a preference for graphs that display positive trends” (Smeuninx et al., 2016, p. 53). Other authors have studied the consequences and costs associated with the readability of narrative-text financial disclosure, and how it can influence the reaction of investors (Lehavy, Li & Merkley 2011; Li, 2008; Rennekamp, 2012; Wang et al., 2018). Consequently “because of these variations, managers’ decisions about narrative disclosures are not neutral (Bowen et al., 2005; Sydserff and Weetman, 1999)” (Wang et al., 2018, p.68) and managers might purposely manipulate readability to the companies’ advantage (Amran et al., 2014; Boiral, 2013; Parsons and McKenna, 2005; Smeuninx et al., 2016). However, measuring readability has been a challenge. Rudolf Flesch (1948) is considered the father of readability numeric measuring techniques in the English language. Edgar Dale and Jeanne Chall (1948), Robert Gunning (1952) and Kincaid, Fishburne, Rogers and Chissom (1975) have also defined popular formulae still in use (Smeuninx et al., 2016). Spanish readability formulae are mostly inspired by English language ones (Moreno & Casasola, 2016).

3.2. Theoretical framework of sustainability disclosure and hypothesis

There are many complementary or overlapping theories that have been used in previous studies to define sustainability disclosure framework (Chan, Watson & Woodliff, 2014; Chen and Roberts, 2010; Cormier and Magnan, 1999; Elijido-Ten, Kloot & Clarkson, 2010; Freeman, 1983; Gray et al., 1995; Hackston and Milne, 1996; Holder-Webb, Cohen, Nath & Wood, 2009; Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Martínez-Ferrero, Ruiz-Cano & García-Sánchez, 2016; Odriozola & Baraibar-Diez, 2017; Reverte, 2009; Snider, Hill & Martin, 2003; Tamimi & Sebastianelli, 2017). Given that stakeholder theory and legitimate theory are frequently used to examine sustainability disclosure (Chan et al., 2014; Freeman, 1984), and that agency theory approach for corporate governance (Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Kaymak & Bektas, 2017) is connected with stakeholder theory, these three theories will be briefly reviewed in this paper.

Stakeholder theory has been frequently used by scholars as a key conceptual framework for evaluation studies on sustainability reporting, and to explain sustainability disclosure (Snider et al., 2003; Tamimi & Sebastianelli, 2017). This might be due to the fact that it unites the constructive aspects of agency theory with legitimacy’s theory normative features (Garriga & Melé, 2004; Odriozola & Baraibar-Diez, 2017). “Stakeholder theory is based on the idea that a firm’s success depends on the alignment of firm and stakeholder interests, implying the importance of firms to listen to, understand, and respond to stakeholder demands and expectations (Clarkson, 1995; Tullberg, 2013)” (Moratis & Brandt, 2017, p. 313). This alignment is more than just maximizing shareholder benefits (Mitchell, Agle & Wood., 1997; Odriozola & Baraibar-Diez, 2017; Phillips, Freeman & Wicks, 2003; Tamimi & Sebastianelli, 2017). It also involves managing the conflicting and complex relationships companies have with them (Ansoff, 1965; Chan et al., 2014; Tamimi & Sebastianelli, 2017) since this might contribute to a company achieving its objectives (Clarkson, 1995; Chan et al., 2014), to its long-term survival (Chan et al., 2014; van der Laan Smith, Adhikari & Tondkar, 2005), and to enhancing company reputation (Chan et al., 2014; Tamimi & Sebastianelli, 2017), among others. Furthermore, stakeholder theory emphasizes the relevance of considering the interests of all stakeholders in a wider sense, whether they affect the company or are affected by it, (Bucholz & Rosenthal, 2005; Jensen, 2001; Moratis & Brandt, 2017; Mitchell et al., 1997; Odriozola & Baraibar-Diez, 2017), and whether they are shareholders, employees, customers, public interest groups, creditors, environment, board of directors, competitors, governmental bodies, the community, NGOs or the media, besides others (Kaymak & Bektas, 2017; Tamimi & Sebastianelli, 2017). Managers play a relevant role in stakeholder theory since “managers develop CSR grams to simultaneously fulfill their moral, ethical, and social duties, while also addressing shareholder expectations regarding financial goals” (Kaymak & Bektas, 2017). Also, managers might withhold information to delay the market’s supervision of their performance (Amran et al., 2014; Karamanou & Vafeas, 2005).

As Martínez-Ferrero et al. (2015) state, one of the mechanisms used to cover the demands of stakeholders is sustainability information disclosure (Odriozola & Baraibar-Diez, 2017). For this disclosure to be effective, stakeholders must give credibility to the disclosed information and it must be quality information (Gray, 2000; Martínez-Ferrero et al., 2013; Odriozola & Baraibar-Diez, 2017). Practices such as being more willing to disclose information when performance is good and overlooking bad information (Clarkson et al., 2008; Mermod & Idowu, 2013; Wang et al., 2018), instead of being transparent and accountable to stakeholders (Amran et al., 2014), or reporting only when there is pressure (Bewley & Li, 2000; Wang et al., 2018), should be avoided, since these practices could reduce credibility and adequacy of Sustainability Reports (Corporate Register, 2013; Luo, Meier & Obeerholzer-Gee, 2012; O’Dwyer, Unerman & Hession, 2005; Wang et al., 2018). Reducing credibility accentuates the “credibility gap”, which is defined as “a situation in which the things that someone says are not believed or trusted because of the difference between what is said and what seems to be true (Merriam Webster Online, 2013)” (Odriozola & Baraibar-Diez, 2017, p. 123). Consequently, as Wang et al., (2018) states on the obfuscating hypothesis, “manipulating readability may serve as a tool for companies to obfuscate inferior CSR information in comprehensive CSR narrative disclosures.” Moreover, Lehavy, Li, and Merkley (2011) show how investors will “rely more heavily on expert analysis as a company’s reporting becomes less readable” (Smeuninx et al., 2016, p. 53).

Legitimacy theory has been frequently used by scholars as their conceptual framework for sustainability disclosure studies (Chan et al., 2014; Cormier and Gordon, 2001; Deegan, 2002; Haniffa and Cooke, 2005; O’Donovan, 2002). Aerts and Cormier (2009, p. 2) state that “environmental legitimacy is significantly and positively affected by the extent and quality of annual report environmental disclosures.” Legitimate theory is based on the concept of a social contract whereby the company compromises to be a good corporate citizen (Chan et al., 2014) and pursues moral legitimacy given by social agents (Branco and Rodrigues, 2006; Scherer & Palazzo, 2011; Wang et al., 2018) by “maintaining socially responsible business strategies and operations (Scherer & Palazzo, 2011)” (Wang et al., 2018, p. 66). If society considers that a company is legitimate by being socially and environmentally responsible (Gray et al., 1995; Reverte, 2009; Odriozola & Baraibar-Diez, 2017; Wang et al., 2018), it will be able to exist and use community resources (Chan et al., 2014; Holder-Webb et al. 2009). If it’s not socially and environmentally responsible, its reputation will be damaged (Amran et al., 2014; Branco & Rodrigues, 2008) and society will threaten that company’s existence by limiting its resources, such as consumer and labor-supply boycotting, reducing financial capital, lobbying on tax increases, fines or prohibiting laws on activities that are not considered legitimate by society (Chan et al., 2014; Tamimi & Sebastianelli, 2017). Considering these circumstances, and the benefits that sustainability disclosures provides, “legitimacy theory relies on the assumption that managers will adopt strategies to demonstrate to society that the organization is attempting to comply with society’s expectations” (Chan et al., 2014, p. 61). To maintain their legitimacy, managers will need to disclose their efforts and achievements to social agents and will be motivated to do it (Wang et al., 2018). For this purpose, they will use an effective communication channel such as sustainability reporting (Chan et al., 2014; Dyllick & Hockerts, 2002; Wheeler & Elkington, 2001). But information disclosure is not homogeneous. Some companies are very rigorous, while others might be pointed out for doing ‘greenwashing’ or ‘window-dressing’ activities (Kim, Park & Wjer, 2012; Schons & Steinmeier, 2016; Wang et al., 2018). These activities aim for the benefits of sustainability disclosure without honestly addressing sustainability issues (Wang et al., 2018).

Moreover, within legitimacy theory, firms that report on sustainability can use community resources (Chan et al., 2014; Holder-Webb et al., 2009) and “have better corporate governance ratings; are larger; belong to higher profile industries; and are more highly leveraged” (Chan et al, 2014, p. 59). Also, the most talented employees are attracted by morally responsible companies (Adams and Zutshi, 2004; Chan et al., 2014) and just the process of giving thought to social and environmental issues for reporting contributes to improved decision-making processes and control systems (Chan et al., 2014). Reports may also improve corporate reputation and image (Adams and Zutshi, 2004; Chan et al., 2014; Clarke & Gibson-Sweet, 1999; Kaymak et Bektas, 2017; Melo & Garrido-Morgado, 2012; Odriozola & Baraibar-Diez, 2017; Wang et al., 2018), corporate relations with stakeholders, (Adams and Zutshi, 2004; and Chan et al., 2014) and financial returns (Adams and Zutshi, 2004; Chan et al., 2014; Flammer, 2013; Torugsa & O’Donohue, 2012; Wang et al., 2018), as well as potentially reducing a capital market’s information uncertainty (Cormier and Magnan, 2015; Martínez- Ferrero et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018).

Agency theory has been frequently used by scholars as part of the conceptual framework for sustainability studies. Agency theory came to document the need of companies to govern the relations between the shareholders (principal) and directors (agent), as well as the relations between directors and management (both agents). “Principal” refers mainly to shareholders, but it can also include investors or outsiders, whereas “agent” refers to director, manager, entrepreneur or insider, (Gutierrez and Surroca, 2014). The principal delegates decision-making responsibilities and the management of their investments or assets to an agent in return for compensation (Gutierrez and Surroca, 2014; Kaymak & Bektas, 2017). However, the agent’s actions might not pursue principal interest, since agents have their own interest to pursue (Rodriguez-Fernandez, 2016; Mitchell et al., 1997; Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Tamimi & Sebastianelly, 2017). This agency conflict is what Villalonga and Amit (2016) call Agency Conflict Type One.

There are different views on reporting within agency theory. Some scholars suggest that managers are not economically incentivized towards opportunistic reporting since the market might identify it and punish the company with share-price reduction (Clarkson et al., 2008). Furthermore, managers might use sustainability narrative for reports as a communication tool to provide relevant information and reduce information asymmetries (which means managers have more information than stakeholders) between the company and the different stakeholders (Arena et al., 2015; Brown & Hillegeist, 2007; Clarkson et al., 2008; Martínez-Ferrero et al., 2015; Odriozola & Baraibar-Diez, 2017; Reverte 2012; Verrecchia, 1983;). Other studies suggest that managers might apply communication tactics (IM hypothesis) to influence share prices to their advantage, as the market is not able to assess short-term reporting (Clatworthy and Jones, 2001). So managers will try to conceal failures and enhance successes “to improve their reputation and compensation, or alter users’ perceptions of corporate achievements in an attempt to convince stakeholders to accept the management’s view of society (Merkl-Davies and Brennan, 2007)” (Arena et al. 2015, p. 348). IM perspective for sustainability disclosure has been frequently used (Joutsenvirta, 2009).

Legitimate theory is an appropriate theory by which to document the relevance of sustainability reporting that details companies’ compliance with laws and regulations, in the search for social legitimacy. Stakeholder theory and agency theory are appropriate theories by which to document the relevance of readability as a manipulation tool in sustainability disclosure narrative text.

Which takes us to the following hypothesis of this study:

Hypothesis 1: Meeting GRI standards on regulatory compliance is positively associated with readability, ceteris paribus

4. METHODOLOGY

4.1. Data selection

This study is based on the universe of Sustainability Reports from 2015 to 2018 of companies included on the Spanish IBEX35 in October 2019. This universe is of 140 reports. Due to the voluntary nature of sustainability reporting (non-financial statements) until 2018 (Directive 2014/95/EU Disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups), to the fact that some companies only partially reported the information, and to the fact that some of the information was too brief to run the readability test on, or it was in English, the number of sustainability reports used was 116, that being the total number of observations. These reports were issued between 2015 and 2018 by the 35 largest quoted companies in Spain as of October 2019.

Sustainability information is sometimes reported as an independent piece, and other times within the Annual Report or by Integrated Reporting. The detailed sustainability information has been manually extracted from the different reports and taken to an Access database.

4.2. Variables

4.2.1. Dependent variable: Readability measures

As far as we know, no previous readability studies on Sustainability Reports in Spanish have been found. Readability studies using the English language (Adelberg, 1979; Courtis, 1998; Laksmana, Tietz & Yang, 2012; Lehavy et al., 2011; Li, 2008; Sydserff & Weetman, 1999; Wang et al., 2018) have mostly applied the Fog, Kincaid, and Flesch indices to measure readability of narrative disclosure in annual and sustainability reports. The Flesch Reading Ease Formula takes into consideration word and sentence length. The score obtained varies from 0-100, and ranks the text on a scale of reading difficulty. Since the Flesch formula was designed for English narrative texts, it could not be directly applied to Spanish narrative texts. The English language uses shorter sentences and words, so a direct application to Spanish texts would result in distorted low scores. Consequently, the formula has been adjusted for Spanish texts (Moreno and Casasola, 2016). Two readability indices for Spanish have been used on this study, both of them based on the Flesch formula (Flesch, 1948); these are the Fernández Huerta Index (Fernández, 1959) and the Inflesz Index by Barrio (2008). This last one was inspired by Szigriszt Pazos (1993).

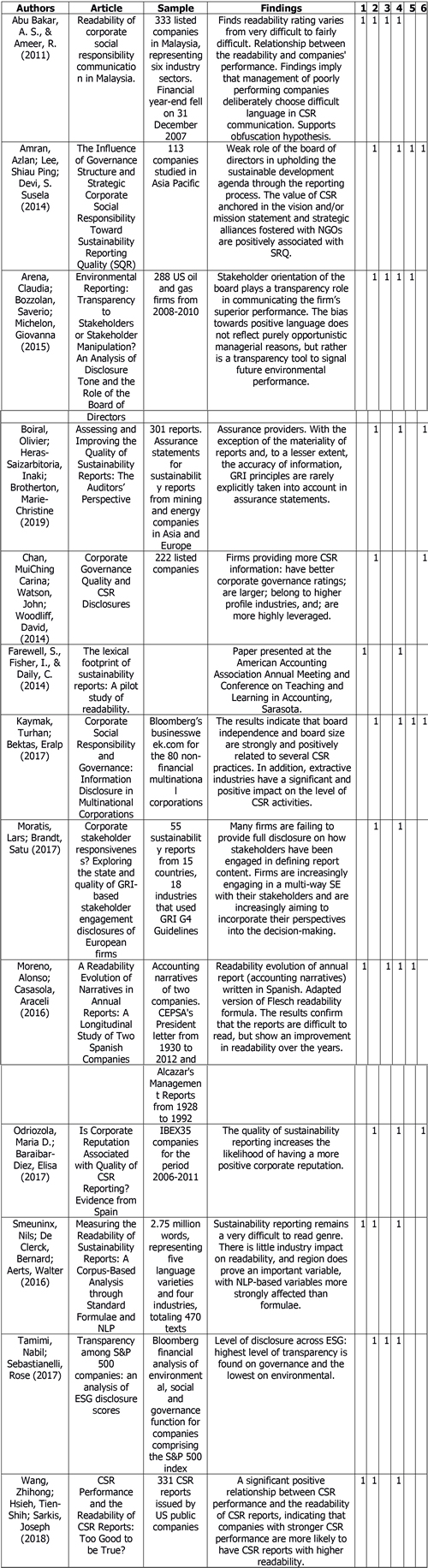

Table 2. Flesch formula scores and their correlation with levels of reading ease, typical magazine.

Source: the content is from public domain. Extracted from Moreno and Casasola (2016).

The Fernández Huerta Index is based on the following formula:

L = 206.84 – 0.60P – 1.02F

where L is the readability; P, the average of syllables per word; F, the average of words per sentence.

The Inflesz Index is based on the following formula:

I = 206.835-(62.3S/P)-(P/F)

where I is the Inflesz scale; S, the total syllables; P, the number of words; F, the number of sentences.

In both cases, results are measured on a scale to 100, where low results indicate more difficulty to understand the text, and high results indicate the opposite. To apply the formulas, the texts extracted from the Sustainability Reports were run through the legible.es program and the results given were registered. The legible.es program is a Python script licensed by the General Public License 3.

Since some companies did not report on all the sustainability studied variables, and some variables gave insufficient information to perform the readability test (the narrative text supplied was too short to study), the data recorded for the study is the average among those reported and suitable for being subjected to the test.

4.2.2. Independent variable: Measures of sustainability compliance

The compliance data on sustainability was gathered directly from the companies’ published Sustainability Reports, collected from the firms’ websites. The assessment has been based on the Sustainability Reporting standard used by Spanish IBEX35 companies, which is the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), using both the recent GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards, as well as the previous GRI4 Guidelines. The GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards were officially launch on 19 October 2016, and reports published on or after 1 July 2018 were required to use them to be considered as such. The GRI Standards are based on the GRI4 Guidelines and there is a Mapping (GRI, 2018) that links both, so the use of one or the other has not been a limitation to this study (Global Reporting Initiative 2020).

The GRI standards considered in this study are those with a high impact in the Bloomberg ESG database (Bloomberg, 2020). Bloomberg ESG is frequently used in academic ESG studies, for example by Pei-yi Yu, et al. (2018) or Tamimi & Sebastianelli (2017). The Bloomberg ESG high impact GRI standards studied are those related to compliance on laws and regulation, since compliance is a function of the board in the UK Corporate Governance Code, FRC (2018). Specifically, the GRI studied are: 205/G4-SO5 Confirmed incidents of corruption; 206/G4-SO7 Legal actions for anti-competitive behavior; 307/G4-EN29 Non-compliance with environmental laws and regulations; 417-2/G4-PR4 Incidents of non-compliance concerning product and service information and labeling; 417-3/G4-PR7 Incidents of non-compliance concerning marketing communications and 419/G4-SO8 and PR9 Non-compliance with laws and regulations in the social and economic area.

We have identified and classified them using a binary score (1-0) for each, with 1 being compliance and 0 being non-compliance. The binary score follows KLD database criterion. The KLD database is often used to research on sustainability performance (Arena et al., 2015; Chatterji, Levine and Toffel, 2007; Cho and Patten, 2007). It was developed by Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini Research and Analytics (Kaymak and Bektas, 2017). Since some companies did not report on all six of the studied GRI, the data recorded for SCOMPL is the total average among the reported ones, to allow for a regression to be run. Total average follows the formula A/(A+B). As mentioned, compliance was recorded with a 1 and non-compliance with 0. The highest value of SCOMPL is 0,50 and it is achieved when the 6 GRI studied are reported and complied with.

4.2.3. Control variables

The control variables used in this study are an overall company performance measure, EBITDA (variable CEBITDA), company assets (variable CASSETS), leverage as total assets divided by total debt (variable CLEVERAGE), as well as the size of the Board (GSIZE).

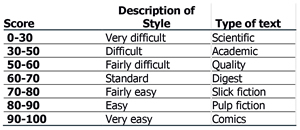

Table 3 shows variables included in the analysis.

Table 3. List of variables.

Source: by author.

4.3. Model specification

Independent variables in this Model is Compliance (SCOMPL - Quantitative continua, Percentage of the Total. Number of GRI Reported).

Fernandez Huerta (FH) and Inflesz indices serve as dependent variables for Readability - Qualitative Ordinary.

The Model represents the relation between two readability indices for Spanish language (FH and Inflesz indices) with laws and regulation compliance on Sustainability Reporting.

Model: READABILITYit = β0 + β1 SCOMP it+ β2 CEBITDAit+ β3 CASSETS it+ β4 CLEVERAGEit+ β5 GSIZEit+ β6 YEAR16 it+ β7 YEAR17 it+ β8 YEAR18 it+ εit

5. DISCUSSION

5.1. Descriptive statistics

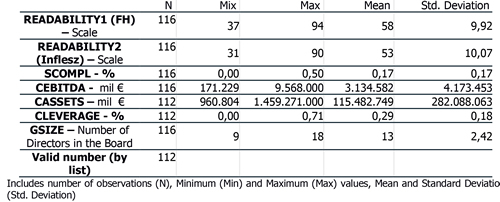

Of a universe of 140 Sustainability Reports of Spanish IBEX35 companies from 2015 to 2018, 116 are considered in this study. Total Number of observations is 116.

The Readability variable for the FH and Inflesz Indices. The number of observations is the same as for Board Composition and Sustainability. To interpret the results, we must know the readability scale for FH, which is: 90-100 very easy, 80-90 easy, 70-80 somewhat easy, 60-70 normal (adult), 50-60 somewhat hard (pre-university), 30-50 hard (basic university), 0-30 very hard (specialized university). As well as the readability scale for Inflesz, which is: 80-100 very easy, 65-80 somewhat easy, 55-65 normal, 40-55 somewhat hard, 0-40 very hard. As we can see in Table 4, the readability average is 58 for the FH Index, which falls into “somewhat hard” and 53 for the Inflesz Index, which also falls into “somewhat hard”. In the FH variable, there were narrative texts that reached the “hard” level, 37 min, and others “very easy”, 94 max. In the Inflesz variable, there were narrative texts that reached the “very hard level”, 31 min, and others the “very easy”, 90 max. Based on the stakeholder theory, since the scope of readers for sustainability reports has widened (Clarkson, 1995; Tullberg, 2013; Moratis et Brandt, 2017), these results suggest that companies should simplify the readability of their sustainability reports to make them easier to read by the different stakeholders who are interested in this information. Furthermore, they should avoid the practice mentioned by Wang et al. (2017), whereby readability is purposely used to obfuscate inferior sustainability information and for greenwashing, to reduce the possible negative reaction of investors towards this information.

The Compliance with laws and regulations -SCOMPL variable- is an average among the reported sustainability information, since some companies did not report on all of the GRI studied. 17% is the average of Compliance. The maximum value of compliance by one company is 50%.

Table 4. Summary of Statistics Includes number of observations (N), Minimum (Min) and Maximum (Max) values, Mean and Standard Deviation (Std. Deviation).

Source: by author.

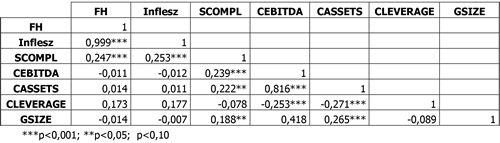

Correlation coefficients between readability and compliance and control variables can be found in table 5.

Table 5. Correlation coefficients between readability and compliance and control variables.

Source: by author.

5.2. Multivariate analysis

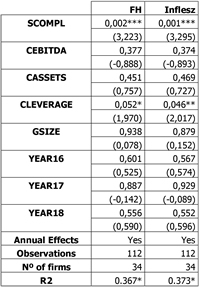

The OLS regression model has been applied to regress Sustainability Compliance on Laws and Regulation with the two readability indices.

The analysis of this regression on FH and Inflesz Indices can be found in Table 6. Table 6 shows how Sustainability Compliance on Laws and Regulation is positively related to the FH and Inflesz Indices. The analysis of other variables also suggests a positive relation between the FH and Inflesz readability Indices and leverage.

Table 6. Regression Model. Compliance and Readability on FH and Inflesz Indices.

Source: by author.

The result on both indices suggests an association between compliance and readability, that high rates of readability are associated with high compliance, and vice versa, as was stated in our hypothesis. This is supported by the findings of Wang et al. (2017). The analysis of other variables also suggests a positive relation between readability and leverage, which means high rates of readability are associated with high leverage.

6. CONCLUSION

This research applies the perspective of the Spanish language to readability studies on sustainability disclosures from boards of directors. Since stakeholders have taken the lead in demanding sustainability transparency, engagement with them has become more important than ever and companies and regulators should make an effort to communicate in a simple manner. They should keep in mind that their target audience might not now be a specialized one and they should simplify the readability of their reports so that they may be understood by their varied receptors, which could include everyone from clients and society to investors, media or others. It’s of interest to emphasize that a proactive stand and clear sustainability communication should be the rule even when there is non-compliance, since one of the outcomes of this empirical study is that a company’s readability becomes more difficult when there is non-compliance, and this practice could be taken as information overload and greenwashing and, consequently, affect a company’s reputation and its legitimacy. There is much to improve on sustainability disclosure readability for IBEX35 Spanish firms. A more precise and standard reporting methodology could contribute to this approach, as well as a systematic and detailed audit review. The roles of regulators, stakeholders, assurance providers and companies are key in this process.

This study contributes to communication, sustainability and board of directors literature with research on readability using the Spanish language. It provides companies and regulators with empirical results on how difficult sustainability disclosure narrative texts are and how there is room for improvement in this communication area. Finally, it suggests a need to be alert when it comes to sustainability reports that are difficult to understand, since it could indicate a lack of compliance.

7. RECOMMENDATIONS

Other fields of investigation could be to study the readability of other GRI reports, and to investigate all quoted companies in Spain, as well as in other countries that report using the Spanish language. Also, doing a further comparison between English and Spanish could be of interest, as could investigations on readability and quality of information, disclosure or auditing. Furthermore, studies could be extended to other corporate governance criteria and readability, such as number of board members, independent directors at the board, gender, or others.

This research has the following limitations: Since there are no other references of sustainability studies in Spanish, the results have been compared with English readability studies. Also, the readability indices used have restrictions when the narrative test is too short. In these cases, the results were not considered. Finally, there were companies that considered that some of the GRI used in this investigation didn’t apply to them because of the type of activity they performed. In these cases, the results were not considered.

AUTHOR

Mónica Cervantes Sintas

Degree in Business Administration and Management, ADE, from Rey Juan Carlos University, URJC, and Marketing Degree from ESIC. Official Master in Strategic Planning of the Company, Analysis and Decision Making at URJC, Professional Expert on Marketing for Exhibitions by UNED, and Community Manager by the UNED Foundation. Proficiency in English from University of Cambridge and Upper Level Cycle in English Language issued by EOI. More than 20 years of experience as a teacher in masters of different Spanish and foreign universities and member of the Project Evaluation Board. Head of Members and Marketing at Instituto de Consejeros-Administradores, IC-A, Spanish association of Directors. Previously she was Marketing Director at SITEL, Marketing and Communication Manager at Red Eléctrica Telecomunicaciones and worked as Head of Marketing and Communication for Spain and Latin America at SINTEL. m.cervantes@alumnos.urjc.es