doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.50.129-147

RESEARCH

THE WEBSITES OF SCHOOLS. ANALYSIS OF THE CURRENT SITUATION IN THE VALENCIAN COMMUNITY

LAS PÁGINAS WEB DE LOS CENTROS EDUCATIVOS. ANÁLISIS DE LA SITUACIÓN ACTUAL EN LA COMUNIDAD VALENCIANA

AS PÁGINAS WEB DOS CENTROS EDUCATIVOS. ANÁLISES DA SITUAÇÃO ATUAL NA COMUNIDADE VALENCIANA

Juan Francisco Álvarez Herrero1

Rosabel Roig-Vila2

1Profesor asociado del Departamento de Didáctica General y Didácticas Específicas de la Facultad de Educación en la Universidad de Alicante (España). Doctor en Tecnología Educativa y Máster Universitario en Dirección y Gestión de Centros Escolares. University of Alicante. Spain

juanfran.alvarez@ua.es

2University of Alicante. Spain

rosabel.roig@ua.es

ABSTRACT

The website has become an essential requirement of any educational center. Beyond being platforms for the information and communication of the entire educational community, today we find that these web pages are also shop windows of the centers. In them, the excellences of these centers are announced and shown and are a claim of educational marketing. Therefore it is essential to know if these “letters” of introduction of the centers have all the elements and characteristics that they must possess. This study analyzed 100 random web pages of non-university educational centers of the Valencian Community (Spain) and it was found that there are quite a few differences between the websites of public centers and those of concerted and private centers. In general, all of them presented occasional deficiencies, among which are: a lack of image and a suggestive aesthetic, lack of information, lack of updating, the non-use or dissemination of the center’s social networks and the non-dissemination or information of the teaching methodologies or the pedagogical style of the center. These problems are motivated by the lack of proper management and maintenance of the web pages, a function that often falls to the ICT coordinators of the center and rarely have time and training to perform this task. Likewise, it was detected that the websites of these educational centers rarely have a pedagogical purpose that encourages and promotes learning.

KEY WORDS: school websites, ICT, educational marketing, web content, Coordinator ICT, educational centers, innovation

RESUMEN

La página web se ha convertido en un requisito imprescindible de cualquier centro educativo. Más allá de ser plataformas para la información y la comunicación de toda la comunidad educativa, en la actualidad nos encontramos con que estas páginas web son también escaparates de los centros hacia la sociedad. En ellas, se anuncian y se muestran las excelencias de dichos centros y son un reclamo del márketing educativo. Por ello, se hace imprescindible conocer si estas “cartas” de presentación de los centros tienen todos los elementos y las características que deben poseer. Este estudio analizó 100 páginas web al azar de centros educativos no universitarios de la Comunidad Valenciana (España) y se constató que existen bastantes diferencias entre las webs de centros públicos y las de centros concertados y privados. En general, todas ellas presentaban alguna que otra deficiencia, entre las que destacan: una falta de imagen y una estética sugerente, falta de información, falta de actualización, el no uso ni difusión de las redes sociales del centro y la no difusión o información de las metodologías docentes o el estilo pedagógico del centro. Estos problemas vienen motivados por la falta de una correcta gestión y mantenimiento de las páginas web, función que muchas veces recae en los coordinadores TIC del centro y que pocas veces disponen de tiempo y formación para desempeñar dicha tarea. Así mismo, se detectó que las webs de estos centros educativos pocas veces tienen una finalidad pedagógica que incentive y promueva el aprendizaje.

PALABRAS CLAVE: páginas web de centro educativo, TIC ,márketing educativo, contenido web, Coordinador TIC, centros educativos, innovación

RESUMO

A página Web se converteu em um requisito imprescindível de qualquer centro educativo. Mais que ser uma plataforma para a informação e a comunicação de a comunidade educativa, na atualidade nos encontramos com que estas páginas web são também vitrines desses centros para a sociedade. Nelas, se anunciam e se mostram as excelências desses centros e são um reclamo de marketing educativo. Por isso, são imprescindíveis conhecer se estas “cartas” de apresentação dos centros têm todos os elementos e as características que devem possuir. Este estudo analisou 100 páginas web aleatoriamente de centros educativos nos universitários da Comunidade Valenciana (Espanha) e constatou que existem bastantes diferenças entre as webs de centros públicos e as de centros privados. Em geral, todas elas apresentavam alguma deficiência, entre as que se destacam são: falta de imagem e estética sugestiva, falta de informação, falta de atualização, o não uso e nem a difusão das redes sociais do centro e a falta de difusão ou informação das metodologias docentes ou o estilo pedagógico do centro. Esses problemas vêm motivados pela falta de uma correta gestão e manutenção das páginas webs, função que muitas vezes recaem nos coordenadores TIC do centro e que poucas vezes dispõem de tempo e formação para desempenhar estas tarefas. Mesmo assim, se detectou que as webs destes centros educativos poucas vezes têm uma finalidade pedagógica que incentive e promova a aprendizagem.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: páginas webs de centro educativo, TIC, marketing educativo, conteúdo web, coordenador TIC, centros educativos, inovação

How to cite the article: Álvarez Herrero, J. F. & Roig-Vila, R. (2019). The websites of schools. Analysis of the current situation in the Valencian Community. [Las páginas web de los centros educativos. Análisis de la situación actual en la Comunidad Valenciana]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, (50), 129-147.

doi: http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.50.129-147

Recovered from http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/623

Received: 06/10/2019

Accepted: 15/10/2019

Published: 15/11/2019

1. INTRODUCTION

The current society in which we are immersed lives on the Internet. This Network has become a resource without which many people could not live. In addition, with the incursion and the current massive use of mobile devices, and more specifically of smartphones, we live permanently connected. All this has meant a revolution in the world as we know it and a change in our habits, customs and activities. Today we buy almost everything on the Internet and turn less to the physical stores of a lifetime. We consume information and leisure through the Internet and this means that the media, such as the press, radio, television, cinema or even the theater, have had to reinvent themselves in the face of this change in the consumption of their services.

There are numerous examples and areas where the Internet has changed traditional habits. In education we have not been oblivious to this change. Internet has changed not only the way of teaching and learning but also the way of giving visibility to educational centers and to what is done in them, to advertise, to serve not only as an information and communication platform but also as the means that enables online training and even the internationalization of an educational center (Yemini and Cohen, 2016).

The website, therefore, is an element that has become essential in any educational center. For example, many families, when looking for an educational center for their children, first consult the website of the educational center (Egido and Manero, 2012) and, if this information is not published, the educational center will immediately be discarded.

Today we seek to be permanently informed and want to know at all times what our children are doing at school (Gilleece and Eivers, 2018). The center’s website becomes an element that allows us to visualize all the activities, projects and progress of our children. In turn, this visualization serves as an advertising element of the center towards society.

The center’s website is not only, therefore, an excellent information and communication tool or platform (Marqués, 1998), but it also serves to publicize and give visibility to the educational center (Dimopoulos and Tsami, 2018), as well as being a means of training, academic management or even as a repository of activities and resources.

As a summary, it can be said that the purposes or functions of a website, according to Bedriñana (2005), are:

All these functions or objectives to be fulfilled by the website of an educational center confer great importance on it, which would imply that it was the object of multiple research and studies on its use and functionality in the educational world, as well as running as a basic element and of utmost importance in every educational center. However, neither the former nor the latter really exists. On the one hand, there are only few studies that have been conducted on the websites of educational centers (Hartshorne, Friedman, Algozzine and Kaur, 2008; Poock, 2005; Tamatea, Hardy and Ninnes, 2008), although we must cite the study we made years ago, where we analyzed 1,115 school web pages of the seventeen Spanish autonomous communities (Roig-Vila, 2003). Besides, there are only few recent studies (Álvarez-Álvarez, 2017; Gilleece and Eivers, 2018; Taddeo and Barnes, 2014; Tardío and Álvarez, 2018).

For all these reasons, we consider the objective of this piece of research is to carry out an analysis of the situation to know in an approximate way the current state of the websites of the non-university educational centers in the Valencian Community.

To perform this analysis with rigor and quality, we consider that we must deepen, not only the functions that the website may have and that we have already mentioned but also the characteristics and particularities that make these websites so unique and important (López, 2007).

On the one hand, it is worth noting the fact of whether they have an organized structure and a careful aesthetic (Torres, 2005). Likewise, in terms of the content it offers, in addition to being truthful and of quality, it must contain all public information that the educational community may need. As an example we can mention the educational project of the center, the annual general programming, the different plans and projects of the center, etc. (Benito, Alegre and González, 2014). On the other hand, it must offer updated content and links that are operational, be accessible to any person, considering any possible disabilities that may occur, be advertising-not-including and have a multilingual character, especially when we are talking about the fact that, in our research, we will analyze the websites of educational centers in the Valencian Community, a community that has two official languages.

It is also important to keep in mind who the website of the educational center is aimed at, or at least to think about who will be its majority audience. The right thing is to talk about educational websites aimed at the entire educational community: students, teachers and families, especially the latter.

Finally, it should be said that there are important aspects such as that the web can allow easy and fast surfing, that any content is not further away than three clicks. It must also allow interaction with the user: not only must it provide contact information with a physical address, an email address and a telephone number but also other channels of communication and interaction with the user must be opened (McCabe and Weaver, 2018), as can be the social networks, present practically already in all the websites of the educational centers (González, 2008; Roig-Vila, 2009). On the other hand, no less important is to disseminate the way in which the school is working: what methodologies or educational style is used in the classrooms (Egido and Manero, 2012) and what services are offered, both extraordinary and basic services.

We are aware that carrying out a web page of an educational center with all the abovementioned functions and features is not without difficulties and problems. Good maintenance and monitoring of the web page means having a good infrastructure with which to create and maintain it. Currently, in the Valencian Community there is the “Mestre a casa” platform that offers public schools a website where to host their web page. Its change to the Wordpress platform has already been announced after years without updates and an obsolete and limited environment. Some public centers as well as many other private and concerted ones opt for free options such as Google Sites or a Blogger or Wordpress blog, but most private and concerted centers opt for private environments created, and sometimes also managed, by private companies.

To all this we must add the management of these web pages regarding who is responsible for their continuous updating and production of content. In this sense, there is quite a diversity in this aspect. As we have already mentioned, in some cases of private and concerted centers there are external companies that are in charge of it, while in most cases, both in concerted, private centers and in all of the public ones, there is work, either from the ICT coordinator, or from a team of teachers responsible for such management (Espuny, Gisbert, Coiduras and González, 2012; Rodríguez-Miranda, Pozuelos-Estrada and León-Jariego, 2014). One way or another, it is a job that, except when commissioned to a private company, is difficult to manage. In many cases this difficulty implies that the web page is not updated or that its aesthetics and content are neglected (Santos, García and Díaz, 2017).

Other problems derived from other more varied conditions cause the web page to have some deficiencies such as: presence of advertising, absence of relevant information, such as the educational project of the center or the general programming of the classroom, little use or total absence of the social networks, absence of aspects that facilitate its being accessible to everyone (Wells and Barron, 2006), and that it does not offer the possibility of being consulted in other languages.

Thus, from all of the above, we set out to carry out this research with the purpose of researching the center’s web pages and their importance within the effectiveness and responsibility of an educational center, as well as the teaching-learning processes derived from it in a specific context such as the Valencian Community.

2. OBJECTIVES

The main objective of this study is to know and analyze the web pages of non-university educational centers in the Valencian Community, but this general objective is associated, in turn, with other secondary objectives to which we also intend to respond, such as:

3. METHODOLOGY

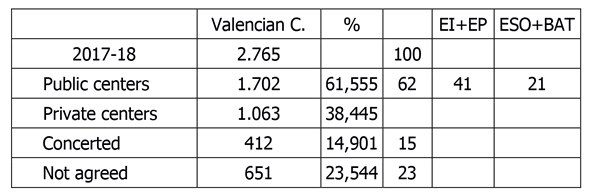

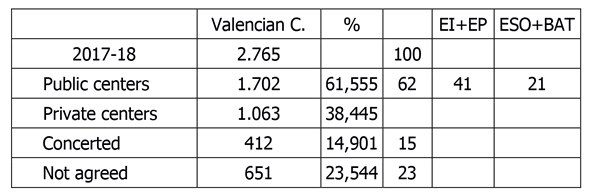

Since the scope of study is the Valencian Community and its non-university educational centers, so as to delimit a sample of study, statistical data were taken from the Statistics of non-university education of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports of the Valencian Community. The ownership of the centers was taken into account, as well as the proportionality of 3 to 1 in the public centers among the preschool and primary education centers with respect to the secondary and high school education centers. Another issue that was taken into account was the different proportionality that exists in the number of educational centers in the three provinces of the Valencian Community. Based on a study sample of 100 web pages, it was distributed in a homogeneous and proportional manner to the number of centers that we found in the Valencian Community, as can be seen in Table 1. Thus, the criteria of previously commented proportionality were taken into account, both in the ownership of the center and in the levels of education taught in publicly owned centers and their geographical distribution.

Table 1. Non-university educational centers of the Valencian Community and proportionality over 100.

Source: Adapted from non-university teaching Statistics.

The sample of web pages was taken at random, without any special criteria, except those already reviewed, in order to maintain proportionality in terms of ownership, educational stages and province of the centers.

As an instrument of analysis, we developed an ad hoc one resulting from taking into account the dimensions and variables taken by Álvarez-Álvarez (2017) in his study, as well as some of the fields considered in the proposal of Marqués (1999) and in our own (Roig-Vila, 2003).

6 dimensions were analyzed: 1.- Identification, 2.- Presentation and organization of information, 3.- Content, 4.- Audience, 5.- Surfing and 6.- Teaching methodologies and services. All of them, in turn, include a series of variables that only offer the possibility of compliance or non-compliance with them, although in some more particular cases there are closed options limited to 3 or 4 possible responses. These dimensions, including their variables and definition, are available on Table 2.

Given that the vast majority of the variables had this dichotomy of response and in the remaining ones also a closed and limited number of possible responses, a descriptive statistical analysis of frequency accounting was performed and the results will appear translated into percentages for a better analysis of them.

Table 2. Dimensions, variables and their definition.

Source: Own elaboration.

To contrast and triangulate the responses obtained from this analysis, the same instrument was passed to 33 ICT coordinators or those responsible for the maintenance and management of the respective web pages out of the total of 100 of the sample and the reliability and coincidence of the responses obtained were verified with those of the study. The analysis was carried out during February 2019.

4. RESULTS

Currently, all non-university education centers in the Valencian Community have a web space on the Internet through which they become visible. Now, as we will see below, there are notable differences between the various centers and their portals or websites, as well as quite widespread deficiencies and errors of use. Next, we analyze the results obtained from this descriptive study according to the 6 studied dimensions: 1.- Identification, 2.- Presentation and organization of information, 3.- Content, 4.- Audience, 5.- Surfing and 6.- Teaching methodologies and services.

4.1. Identification

As already mentioned, according to the different ownership of non-university educational centers in the Valencian Community, in our sample of 100 centers, 62 public centers were taken (41 of Preschool Education and Primary Education, and 21 Secondary Education and Vocational Training Cycles), 15 integrated concerted centers (with levels of education ranging from Preschool Ed to Secondary Ed) and 23 private centers.

The authorship of these web pages is rarely shown. Thus, in the case of public centers, by having a portal such as “Mestre a casa” offered by the Ministry of Education itself, already in its definition it establishes that the web environments provided by “Mestre a casa” are designed, created and maintained by the portal users themselves, without their authorship being defined more precisely.

In the case of private centers and in the vast majority of concerted centers, the web pages have been made by private companies and it is shown in them, although maintenance and management, as in the case of public ones, is carried out by teachers or the center’s ICT coordinator. Only in two cases was no reference found to the authorship of the center’s website or to the name of a company, or to the name of teachers in the center.

Regarding the licenses for the use of the different web pages, we found the same results as what we saw before regarding authorship. Both the web pages dependent on the “Mestre a casa” portal and those belonging to companies or private entities are subject to Copyright and only in those cases in which blogs or free resources available on the Internet are used, use of other types of licenses is made, which in most cases are due to Creative Commons licenses. Only in 4 cases they had this type of Creative Commons licenses, while the remaining 96 had Copyright.

4.2. Presentation and organization of information

As already mentioned, publicly owned centers have a web space assigned on the “Mestre a casa” platform, and it is here, therefore, where the web pages of public centers are hosted. However, among the 62 web pages of public centers tested in this research, two public centers have been found that have resorted to other options (a WordPress blog and a Google site respectively) to host their web pages in parallel to their spaces (abandoned or undeveloped) in “Mestre a casa”.

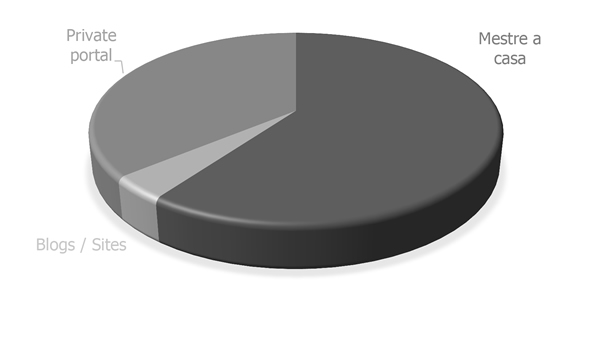

In total, without regard to the ownership of the centers, we found that 60% make use of the “Mestre a casa” platform, 36% use a private portal and only 4% make use of some free resource or tool such as WordPress and Blogger blogs, or the Google Sites (see Graph 1).

Source: Self made.

Graph 1: Portal where the respective web page is hosted.

Concerning the image, aesthetics and design of the web page, we have only taken into account a very general criterion in which it has been considered whether the care and aesthetics of the website invites or not to visit it, and whether the appearance is cared for or, on the contrary, offers a sense of abandonment and neglect. We found that only 54 of the websites offer a pleasant sensation, with a welcoming message, with suggestive images and adequate font size and style.

46% of the remaining pages give a sense of abandonment, of not taking care of the aesthetic aspects in terms of presentation, image and suitable text. There is an important difference based on the ownership of the centers, because, out of the 46 pages that have a poor aesthetic, 43 of them belong to publicly owned centers. In their defense, it must be argued that the “Mestre a casa” portal offers few possibilities for personalization and “customization” and, having a fairly rigid structure, it limits the ability to create a friendly and attractive environment.

Regarding organization, there is a high percentage of well organized and structured web pages. They have menus and buttons that facilitate the classification of the information available in them. Only in 3 of the cases we analyzed, either because of absence of a structure or because of its chaotic presence, we can say that the organization of the website does not correspond with a previous organizational design.

4.3. Content

The information that a web page must provide is one of its basic pillars for any user who accesses it. Thus, the information must be nurtured, varied and updated. Regarding the amount of information, we found that in 43 of the cases we analyzed, it is rather null or scarce. This percentage is worrisome, and more so in our days where the Internet is crucial in our society and is the main source of information for today’s citizens. Likewise, it is again worrisome that, of these 43 cases, the vast majority of them correspond to websites of public centers (38), in which, on their “Mestre a casa” websites, they only offer the basic information established at the beginning of each school year by the Conselleria itself and little else.

The same happens with the official documents. As established in the LOMCE in its article 121.3 and 121.6 and the order EDU/25/2010, the educational projects of the centers must be public. In this sense, we found that, in 56 of the analyzed cases, such information is not available, as well as other plans: coexistence, ICT, reader, attention to diversity, etc. In this case, the responsibility for making this information public is more distributed: out of the 56 detected cases, 37 correspond to public centers, 8 to concerted centers and 11 to private centers.

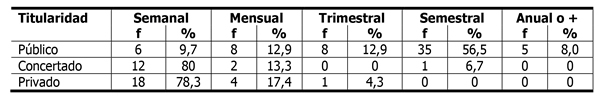

Worrisome is the great difference between public and concerted and private centers concerning the updating of the contents. In public centers, only 22 of the 62, that is, 35.5%, maintain an updated web page with at least a quarterly frequency and, on the contrary, in concerted and private centers the percentages of web pages updated with at least a monthly frequency exceeds 90% in both cases as can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3. Frequency of updating the website according to the ownership of the center.

Source: Own elaboration.

The predominant content support on the home page of the website also has quite considerable differences between public and private centers, but this is mainly due to the few possibilities that the “Mestre a casa” platform offers to the web pages of public centers. Although it allows the insertion of both images and videos, its difficulty of insertion, its low quality, the dependence of other open resources such as repositories of public videos, compliance with the law on protection of student data, etc., in many cases, make its use rejected. Thus, in the web pages of public centers, in 44 of them (71%) the text format predominates over the audiovisual format. On the other hand, in the concerted centers the image predominates in 14 pages of 15 (93.3%) and in the private ones the image is present in all of them (23, 100%).

The little attention to the accessibility of the web pages of schools is quite worrisome, because in none of the 100 analyzed cases we could find any type of surfing resource or facility without barriers in those people with some type of disability.

The update of the external links offered by the web pages is quite remarkable, at least in the centers of concerted and private ownership, since no case of expired links was found. However, it is not the case of public centers, where 8 of the 62 websites (12.9%) of analyzed public centers had non-operational links.

Regarding the possibility of finding advertising on the websites, the figures weigh against the centers of a concerted nature (in 4 of the 15 direct or indirect advertising, 26.7%) and private (in 7 of the 23 analyzed web pages advertising was found, 30.4%), as compared to no page in the case of public centers.

Regarding the multilingual nature of the web pages, some prior considerations have to be made, because although the public centers through “Mestre a casa” offer the possibility of a bilingual character (Valencian and Spanish), this is not entirely real, it is only limited to the structure of the web - the translation of the titles of the menus, of the sections and subsections that the web presents - but not the content, which is written only in one of the two languages. The same can be said for the web pages of most of the private and concerted centers that offer this possibility: when the contents are accessed, they are in one language or another. We only have to review a case of all those analyzed in which there is complete bilingualism and which corresponds to a private center of marked French linguistic character and presents all the contents of the website in Spanish and French.

4.4. Audience

As we have already mentioned in the introduction of this study, every educational website should be a support and a useful tool for the educational community and this includes, at least, the three main groups of this community: students, teachers and families. When we go to analyze the audience to whom the 100 analyzed web pages are directed, we find that in 100% they are focused on informing and helping in the dissemination and knowledge of the center to families.

Regarding the teaching staff, sometimes they can have their space in these websites and this is verified in 89 of them, although it must be pointed out that all the web pages supported by “Mestre a casa” have been considered. In them, the possibility is offered to the teaching staff of the center to link with their blogs or spaces within the same platform, although in many cases these spaces are not used or stopped being used for a long time.

With all this, only in 4 websites of concerted centers and in 7 of private centers there is no content, no possibility of use or usefulness for teachers. On the other hand, it is very worrisome that students are not given the option of making useful and productive use of the center’s website as a resource and / or another tool in their teaching-learning process. In no web of the public centers this option is given and it only occurs in the case of 3 of the concerted ones and in 8 of the private ones.

4.5. Surfing

Surfing a web page has to be agile, fast and direct. Therefore, in a web page we must be able to find or access that information or content that we look for in less than three mouse clicks. Fortunately, in all the cases we analyzed, this three-click rule is met. However, there has been some case in which the possibility of interaction and communication among the various agents of the educational community or between the surfer and the center does not occur.

Beyond the communication that can be established by offering contact information, such as the physical address of the center, the telephone number and the email address, there is the offering of some other type of resource or medium with which surfers and centers can be connected. Although in the totality of the analyzed cases these commented data are provided (address, telephone and email address), when we talk about another type of communication and interaction such as chats, opinion polls, participation forms, possibility of making comments, etc., it only occurs on 12 websites (5 of concerted centers and 7 of private centers).

A separate case deserves the analysis of the use of social networks and their dissemination on the center’s website, because, although it occurs in all the private and concerted centers, the same does not occur in public centers, where it only occurs in 19 of the 62 centers (30.6%). Thus, there is a wide use of Facebook as well as a growing use of Instagram as compared to other social networks that experience some regression in their use and dissemination, as is the example of Twitter.

4.6. Teaching methodologies and services

It is very important that the use of the website of the center goes beyond being a showcase in which to show families the excellence of the center so that it is considered the perfect candidate in the possible choice of a school for their children. However, we cannot forget that one of the first things that families looking for a teaching center do for their children is to search the website of the candidate centers.

When it is accessed, the services offered and the teaching methodologies or educational style they use are sought. In the analysis of these two aspects we have found an uneven result, because, although 100% of the websites mention the services they offer (school canteen, extracurricular services, school transport, AMPA, etc.), it does not happen with the dissemination or information of the educational style of the center or the educational methodologies that are used. Again we found a big difference between public and private and concerted centers. In the latter, virtually all of them (in 14 out of 15 of the concerted centers, and in 22 out of 23 of the private ones) mention or even boasts about the methodologies used in their model or learning style. On the other hand, in public centers, it only occurs in 18 of the 62 web pages we analyzed (29%).

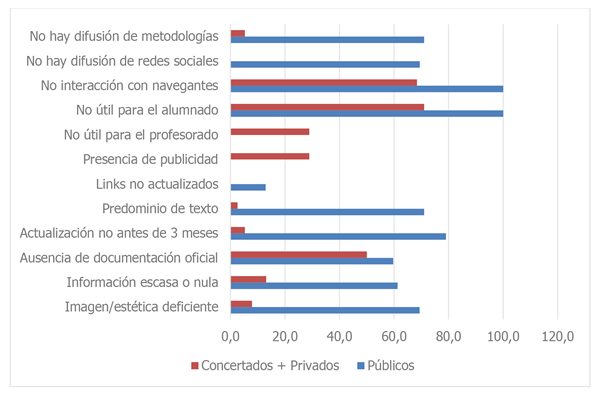

By way of conclusion, Graph 2 shows those variables in which the differences between public and concerted and private centers are most relevant.

Source: Self made.

Graph 2: Differences in the percentages of different variables between public and concerted and private centers.

5. DISCUSSION

Based on the results obtained in this piece of research, it was verified that the characteristics of the web pages of the non-university education centers of the Valencian Community are quite diverse. Even so, some conclusions can be drawn, new hypotheses and future lines of research in this field of research can be established.

In general, it should be said that, when verifying that all of the centers chosen at random from among all the non-university educational centers of the Valencian community have a web page, it is representative in the sense of the generalized existence of a page web in any educational center.

Now, such an optimal result cannot be applied to the three specific objectives we set at the beginning. Thus, according to the first objective, regarding the main problems that web pages have, we cannot ignore the second objective, because, as we have seen, there are marked differences between the web pages of public centers and those of concerted and private centers. Thus, the web pages of public centers have, as main problems, a lack of image and attractive aesthetic on their websites, lack of information, lack of updating, predominance of text over the audiovisual resource, non-use or non-dissemination of the social networks of the center and non-dissemination or lack of information on the teaching methodologies or the pedagogical style of the center.

On the contrary, the concerted centers have other problems such as presence of advertising on their websites, or not being useful for teachers. As problems common to the three types of ownership of centers, we found lack of official documents, not being useful for students or not offering more interaction with surfers than the strictly necessary (physical address of the center, telephone and contact email address).

As we can see, it is possible to verify, not only a large number of problems, but also a clear difference between the websites of public centers and those of concerted and private centers. In most cases, they are correctable problems and, perhaps, a new platform that replaces “Mestre a casa” can solve many of these deficiencies as well as reduce the differences between public and private and concerted centers.

It is also worth noting a problem present in the centers, which 33 out of the 100 ICT coordinators we interviewed have mentioned, management and maintenance of the web pages. These coordinators express the difficulty of managing and maintaining the websites of the educational centers. The main difficulties that are echoed are lack of hours for their management, as well as the difficulty and little training existing for it (we must not forget that we are talking about teachers who are not trained for these tasks). As long as this issue is not resolved, these problems that we mentioned will not disappear. In addition, this issue seems to be more complicated to solve among public centers than between private and concerted centers, because they cannot afford private companies to perform their tasks.

Finally, in relation to the third objective, with regard to knowing the usefulness or purpose that is conferred from the educational centers to their web pages, we have been able to verify two important aspects. On the one hand, it is possible to say that the web pages of the educational centers are conceived and maintained as shop windows or means for the dissemination of the excellence they present. This leads to the second aspect, which is that the web pages are not considered means or resources that can serve the main and ultimate purpose of education such as allowing, promoting and strengthening the teaching-learning processes of students, mainly, but also of the rest of the educational community. We consider this last aspect pressing, because there is a danger that the web pages of educational centers end up being only elements of educational marketing.

Finally, it should be noted that we are aware of the limitations of this study, derived from aspects about the possible bias of the evaluator, the sample, etc., but we consider that, due to the little research on this subject, it is interesting as a first approach and analysis of the current reality of the educational web pages of the Valencian Community. This is how we set a goal to continue researching this field and expand the study to a larger and more representative sample that gives us more reliable data of reality that, as we have already seen, seems complex and worrisome. In this same sense, we consider it interesting to establish, as possible future lines of research, the proposal of a training plan in the management and maintenance of educational websites and awareness and usability as means and resources to promote and encourage the teaching-learning process from the educational centers’ web pages to the entire educational community.

REFERENCES

AUTHORS

Juan Francisco Álvarez Herrero

Doctor in Educational Technology from the Rovira i Virgili University. Associate Professor of the Department of General Didactics and Specific Didactics of the University of Alicante and member of the research group: EDUTIC-ADEI (Education and Information and Communication Technologies - Attention to Diversity. Inclusive School) of the same university. His research is especially interested in the implementation of emerging pedagogies and active methodologies, digital competence, personal learning environments and social networks in the educational world.

juanfran.alvarez@ua.es

Orcid ID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9988-8286

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?hl=es&user=DbUP2SkAAAAJ

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Juan_Francisco_Alvarez

Academia.edu: https://alicante.academia.edu/JuanFcoAlvarez

ResearcherID: http://www.researcherid.com/rid/L-2850-2017

Rosabel Roig-Vila

Doctor in Pedagogy and full professor at the University of Alicante of the Didactics and School Organization Area. She has been dean of the Faculty of Education and is currently the director of the Institute of Education Sciences at this university. She is director of the Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research and coordinator of the research group EDUTIC-ADEI (Education and ICT-Attention to Diversity. Inclusive School). His research focuses on the articulation of ICT in Education.

rosabel.roig@ua.es

Orcid ID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9731-430X

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=VSec3AkA

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rosabel_Roig-Vila

Academia.edu: https://alicante.academia.edu/rosabelroigvila

ResearcherID: http://www.researcherid.com/rid/D-5586-2014