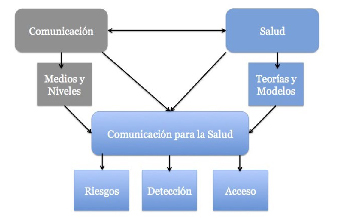

Image 1. relationships between communication and health.

doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2020.51.169-183

RESEARCH

COMMUNICATION FOR HEALTH: EPIDEMIOLOGICAL AND SOCIOCULTURAL APPROACHES TO THE SICK-BODY OF WOMEN WITH BREAST CANCER

COMUNICACIÓN PARA LA SALUD: APROXIMACIONES EPIDEMIOLÓGICAS Y SOCIOCULTURALES AL CUERPO-ENFERMO DE LAS MUJERES CON CÁNCER DE MAMA

COMUNICAÇÃO PARA SAÚDE: APROXIMAÇÕES EPIDEMIOLÓGICAS E SOCIOCULTURAIS AO CORPO-ENFERMO DAS MULHERES COM CÂNCER DE MAMA

Ester Cofré-Soto1. Matron of the Breast Pathology Unit of the Regional Hospital of Temuco Harnán Henríquez Aravena. PhD student in Communication Universidad Austral de Chile and Universidad de La Frontera.

1University Austral de Chile and University of La Frontera. Chile

ABSTRACT

This work is part of the studies of communication for health, specifically in the need for a systematization of epidemiological information on breast pathology in the region of La Araucanía to carry out a focused and relevant communicational design for the population of women and their social and cultural contexts, with the purpose of creating awareness in self-examination, risk factors, periodic controls, etc. In this sense, the intention is to revisit the interdisciplinary tradition of communication for health, in which the formal communication strategies are combined with the discourses and practices of the participating actors, in this case women from the Araucanía region. The main objective of this research is to analyze the notions of body and disease from a critical perspective, which allows a better understanding of the social and cultural context of women. The above, together with the epidemiological background of breast cancer in La Araucanía region, constitute the basis for thinking about a located, pertinent and efficient communicational design.

KEY WORDS: Communication, Health, cancer,body, representations, disease, epidemiology

RESUMEN

Este trabajo se enmarca en los estudios de la comunicación para la salud, específicamente en la necesidad de una sistematización de la información epidemiológica sobre patología de mamas en la región de La Araucanía para realizar un diseño comunicacional focalizado y pertinente a la población de mujeres y sus contextos sociales y culturales, con el propósito de crear conciencia en el autoexamen, los factores de riesgo, los controles periódicos, etc. En este sentido, se pretende retomar la tradición interdisciplinaria de la comunicación para la salud, en la cual se conjugan las estrategias formales de la comunicación con los discursos y prácticas de los actores participantes, en este caso las mujeres de la región de La Araucanía. El objetivo principal de esta investigación es analizar las nociones de cuerpo y enfermedad desde una perspectiva crítica, que permita comprender mejor el contexto social y cultural de las mujeres. Lo anterior, junto a los antecedentes epidemiológicos del cáncer de mamas en la región de La Araucanía, constituyen las bases para pensar un diseño comunicacional situado, pertinente y eficiente.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Comunicación, Salud, cáncer, cuerpo, representaciones, enfermedad, epidemiología

RESUME

Este trabalho se enquadra nos estudos da comunicação para a saúde, especificamente na necessidade de uma sistematização da informação epidemiológica sobre patologia de mamas na região da Araucanía para realizar um desenho comunicacional focalizado e pertinente à população de mulheres e seus contextos sociais e culturais, com o propósito de criar consciência em um alto exame, os fatores de risco, os controles periódicos, etc. Neste sentido, pretende-se retomar a tradição interdisciplinaria da comunicação para a saúde, na qual se conjugam as estratégias formais de comunicação com os discursos e práticas dos atores participantes, neste caso as mulheres da região da Araucania. O objetivo principal desta investigação é analisar as noções de corpo e enfermidade desde uma perspectiva crítica, que permita compreender melhor o contexto social e cultural das mulheres. O anterior, junto aos antecedentes epidemiológicos do câncer de mama na região da Araucania, constitui as bases para pensar em um desenho comunicacional situado, pertinente e eficiente.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Comunicação, Saúde, câncer, representações, enfermidade, epidemiologia

Correspondencia:

Ester Cofré Soto: University Austral de Chile and University of La Frontera.

ecofre278@gmail.com

Received: 30/09/2019

Accepted: 06/11/2019

Published: 15/03/2020

How to cite the article: Cofré Soto, E. (2020). Communication for health: epidemiological and sociocultural approaches to the sick-body of women with breast cancer. [Comunicación para la salud: aproximaciones epidemiológicas y socioculturales al cuerpo-enfermo de las mujeres con cáncer de mama]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 51, 169-183. doi: http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2020.51.169-183

Recovered from http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/620

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. General epidemiological background

Cancer is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cancer accounts for approximately 15% of the world’s deaths; being the pulmonary (19%), the hepatic (9%), the colorectal (9%), the gastric (8%) and the mammary(1) (7%), those that cause the highest number of deaths (WHO, 2017).

(1) In 2015 “8.8 million deaths were attributed to this disease”, of which 571,000 correspond to breast cancer; according to WHO statistics (2017).

For its part in Chile, according to the study of the Association of Isapres de Chile (2017), “cancer is the second cause of death in our country, after cardiovascular diseases. 1 out of every 4 deaths in Chile is caused by tumors, with just over 26,000 people dying per year for this cause”. This information is supported by the Health Statistics and Information Directorate (DEIS), which adds that “in some regions of the country it is already the leading cause of death, since cardiovascular risk factors are being better controlled”; so according to estimates from the Ministry of Health (MINSAL) by 2020 this disease will be the leading cause of death in the country”. Finally, this study shows that among “The cancer most treated by GES is breast cancer (37%)”.

Despite all the above, unfortunately, according to this same study “Chile does not have good statistical records regarding people affected by cancer, which makes it difficult to build public health programs and distribute resources”; the most serious problem being the fact that we do not have information “regarding the people affected by cancer, the type of cancer and sex and age of the patients, as well as the location of these patients”.

In this sense, the objective of the National Cancer Program is to “Reduce the mortality rate, by means of early, appropriate and adequate diagnosis and treatment of quality” (Báez, 2017).

If we are in the most specific field of the research “In women, breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide, with an estimate of 522 thousand deaths in 2012, with a standardized mortality rate of 12, 9 per 100,000 women and an incidence rate of 43.3 per 100,000 women, which corresponds to 25.2% of the incidence of cancer in this group” (Icaza, Núñez and Bugueño, 2017). One of the relevant aspects of this study is that “The relative risk of breast cancer mortality in women in Chile at the community level was positively associated with education and negatively with the percentage of rurality” (Icaza, Núñez and Bugueño, 2017, p. 111). These associations have also been registered internationally (Singh, Williams, Siahpush and Mulhollen, 2011). According to the study “This could be explained by the higher prevalence of hormonal risk factors in women living in urban communes and by differences in the stages of the epidemiological transition throughout the country [although] in developed countries this increased risk in urban areas has moved to the rural sector, due to factors related to the detection and access to timely treatment” (Icaza, Núñez and Bugueño, 2017, p. 112).

Studies agree that the challenges are of a different nature and range from:

Extend the age of mammograms.

Accredit the breast imaging centers.

Improve coverage.

Reach indicators similar to those of the OECD or of developed countries.

1.2. Communication for health: an interdisciplinary approach

The field of communication in/for health is not new. In fact, one of the founding milestones corresponds to the “therapeutic communications group” created in 1972 within the International Communication Association (ICA) and which in 1975 was renamed “communication for health (Health Communications)” ; However, “it is weak in the communication and public health schools of Latin America, where both disciplines almost do not talk to each other, except in very specific subjects” (Busse and Godoy, 2016). On the other hand, the experience in American universities shows the important advances in collaboration between both disciplines, especially in research (Alcalay, 1999). However, this work “has not been systematic, but it has rather reactively responded to the imperative need to include the aspect of communications in health promotion” (Alcalay, 1999, p. 195).

This research is framed in this line, therefore it seeks to articulate the knowledge of communication and health and from here: (a) open an interdisciplinary dialogue, (b) place communication as a field that not only provides strategies and instruments, but also allows an understanding of health processes, and (3) place health as a communicative and cultural fact. As a synthesis, it is a question of studying “how the science of communications acquires social relevance by contributing to other areas of human activity - in this case to health - theories, concepts and techniques to improve the well-being of the population” (Alcalay, 1999, p. 195).

In this same sense, it is about understanding health as a discourse and practice that is carried out in the particular contexts of communication and culture; Therefore, it is relevant, on the one hand, to identify the theories, models and concepts present since the long institutionalized tradition of health communication (Mosquera, 2003), such as:

The Theory of Social Learning.

The Health Belief Model.

The Innovation Dissemination Model.

The Communication Model for Social Change.

As it is also important, on the other hand, to identify the discourses and practices of the different actors and agents involved, especially through the different means available as the levels of

communication present (Coe, 1998), such as:

Communication at interpersonal level.

Communication at the collective level.

Communication at the organizational level.

Use of public media.

The foregoing, specifically regarding the communication of possible risks, the early detection of problems and timely access to information and treatment.

Source: own elaboration.

Image 1. relationships between communication and health.

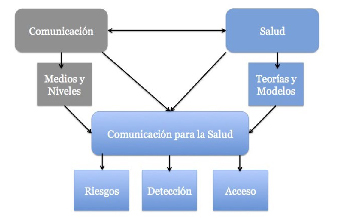

1.3. Breast cancer

Breast cancer consists of abnormal growth and accelerated, disorderly and uncontrolled proliferative of glandular epithelial cells, breast ducts or lobules -that is, in breast tissues- with a high dissemination capacity. It is, ultimately, about cells that have greatly increased their reproductive capacity. Even if it occurs in both men and women, it is rare in the former. Histologic types most often are ductal carcinoma and the lobular carcinoma (MINSAL, 2015).

Source: Santaballa, Ana (2017).

Image 2. anatomy of the female breast.

Causal agents recognize genetic, family and behavioral factors; being from 5% to 10% of hereditary character and about 85% sporadic.

Among the factors risk of a woman for the development of breast cancer, we find:

Ethnic-racial aspects. Evidence in the United States shows a higher incidence in white women than in color (Harris, et al., 2011).

Age. In most cases, it develops in women over 50 years.

The personal history of the disease. If the woman has previously had the disease, the risk of having it is higher.

The family background of the disease. It is hereditary when: (i) there are cases of first-degree relatives (mother, sisters and children), with breast or ovarian cancer, especially before the age of 50. If they are two relatives of first degree, the risk increases 5 times average; (ii) many close relatives (grandparents, uncles and aunts, nephews and nieces, grandchildren and cousins) with breast or ovarian cancer, especially before 50 years.

The genetic predisposition. There are several hereditary genes linked to the risk increase of the disease. The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are the most frequent known mutations.

The personal history of ovarian cancer.

Early menstruation and late menopause.

The age and duration of pregnancy. Women who have had their first pregnancy after age 35 or who have never had a term pregnancy have a higher risk of the disease.

The use of hormone replacement therapy after menopause increases the risk.

The use of oral contraceptives or birth control pills slightly increases the risk. This is still under investigation.

The typical hyperplasia of the breast. This diagnosis increases the risk.

The density of the breast. A dense breast tissue may make it difficult to detect a tumor on a mammogram.

On the other hand, among the factors associated with lifestyle, we find:

Weight. Obesity favors cancer.

Physical activity. Its decrease is associated with a greater risk of cancer occurrence and recurrence after treatment.

Alcohol. Consuming one or two alcoholic beverages (beer, wine and liquor) each day is associated with a greater risk of cancer of occurrence and recurrence after treatment.

Foods. While there are no reliable studies on the relationship of certain foods and risk reduction, eating more fruits and vegetables and fewer animal fats is associated with health benefits.

Other relevant risk factor for this research are the ones of socio-economic nature, according to which, women of higher socioeconomic status of the different ethnic groups have a higher risk of developing breast cancer than women of lower socioeconomic levels of the same groups. So far, the reasons for these differences are unknown; however, they may be related to variations in diet and environmental exposures. On the other hand, it should be noted that in the case of women with higher socioeconomic status, the diagnosis is earlier and, therefore, survival is higher (Asco, 2018).

Finally, another risk factor corresponds to exposure to ionizing radiation at an early age, which may increase the risk of the disease.

Although the recommendations do not match, the most important international institutions about this disease, agree that starting mammography for early detection -annually- at the age of 40 years can save lives. In fact, according to the US Health and Human Services Department (HHS, its acronym in English), women aged between 40 and 74 who go through early detection mammogram have a lower risk of dying of breast cancer than women who do not have them performed on them.

For its part, the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) recommend that, beginning at age 40, women who present a risk average of breast cancer undergo an early screening mammogram every year. The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends that women between 40 and 44 consider taking early detection tests.

For ACS, early screening mammography should start at 45 and be done every year until 55; after which they can have them every other year. The United States Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that early detection exams for women at risk average should begin at age 50 and have it done every other year. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) advises women who have had breast cancer -and those who are at high risk due to a family history of breast cancer- to seek professional medical advice regarding the frequency of exams and on whether they should start before age 40. The age at which mammography should be stopped has not been firmly established, but in general, it is thought that early detection should continue while the woman is in good health, regardless of age.

Women with a high risk of breast cancer should follow different guidelines. According to the recommendations of the American Cancer Society, most women at high risk should begin early detection with a Nuclear Magnetic Resonance of the Breast and a mammogram at age 30 and continue to do so. Some women at high risk may begin early detection with Breast Nuclear Magnetic Resonance at age 25. It is important to remember that most breast cancers occur in women without risk factors.

To carry out the early detection of breast cancer, it is mainly considered:

Clinical breast exam. The doctor carefully feels the breast and armpit to detect lumps or any other unusual thing. Women can perform a self-exam.

Mammography. Exam with X-rays. Generally, two images of each breast are taken, one image generating a view from the top to the bottom and another one producing an angle view from side to side.

1.4. The body in sociocultural context

In this paper we are interested in critically understanding the notions of body and illness, that is, not only in its biomedical dimensions, it is very relevant to consider the psychological, social and cultural context of women with breast cancer, specifically the forms of self-representation that they have about their sick body . In this sense, we need an appropriate approach to observe these conditions, for which a particular bibliography has been used, which is obviously in the process of being searched.

In the first place, it is an object of little recurrent study in the social sciences, despite its presence: “Contemporary sociology has little to say about the most obvious fact of human existence, namely that human beings have, and to some extent they are bodies” (Turner, 1989, p. 57).

Secondly, it is important for a critical study of the body in the society and culture like this, to know that is not about writing a treatise on the society and physiology, but to account for a number of dimensions and aspects involved (Turner, 1989, pp. 66 and 67):

For the individual and the group, the body is simultaneously an environment (part of nature) and a medium of the self (part of the culture).

A differentiation between the body of the populations and individuals’ body [where] the body of the individual is regulated and organized in the interest of the population.

The body lies at the center of political struggles.

Most of the forms of sociological theorization establish a drastic separation between the self and the body.

Following with the foregoing , Le Breton “The physical presentation seems to have value socially as moral presentation” ( 2002, p. 82 ), in the sense of a moral code that allows to put on stage appearances for appraising look and the social prejudice of others, especially based on details of the garment, the body or the face. It is about stereotypes that are established from physical appearances and “are quickly transformed into stigmas, fatal signs of moral defects or belonging to a race” (idem).

Because of what has been said above, it is important to consider the magnitude of the physical aspects of the diseased body, since it is not only a physiological condition, but also a moral one. It is not only a sick-stereotyped body, but evaluation of the social judgment of the group (family, friends, co-workers, neighbors). It is a sick-body observed and at the same time valued and judged.

On the other hand, since this research is on a sick body, that is the woman ‘s body with breast cancer, it is especially interesting considering the way in which women “accept or deny their illness, how they interpret it and pay attention to its most absurd aspects [because] all this constitutes one of the most essential significances of the disease” (Foucault , 1984, p. 66).

In this sense, the self-observation of the diseased body is another key condition, because in addition to acceptance and rejection, there is a process of constant interpretation of everything that happens daily in that body. Self-observation is continuous.

For its part, as in the research, the objective is to account for the sick body and take this condition, the concepts of care and self-care play an important role, not only in a preventive sense, but also in a healing one; where caring is understood as “an act of life that allows life to continue and develop and thus fight against death; it is also to maintain life by ensuring the satisfaction of a set of essential necessities for life” (Colliere, 1993, p. 5). While the self-care is presented as “the contribution of the individual to his own existence, it is a learned activity and oriented to the goal to regulate the factors affecting the development and operation itself for the benefit of their life, health or welfare” (Orem, 1999, p. 177).

This way, self-observation on the diseased body obeys a greater purpose that is care, that is, a condition that imposes an individual and collective purpose on observation, because it is accompanied by medical observation.

2. OBJECTIVES

2.1. General

Understand the notions of body and disease from a critical perspective, together with the epidemiological background, as part of the social and cultural context of women with breast cancer in the Araucanía region in order to think up a located convenient and efficient communicational design.

2.2. Specific

Identify the epidemiological characteristics of breast cancer in the Araucanía region.

Analyze the notions of body and disease from a critical perspective.

Think up a located convenient and efficient communicational design to influence early detection and access to a timely, adequate and quality treatment of breast cancer.

3. METHODOLOGY

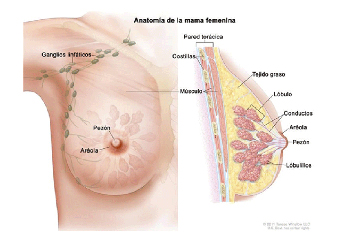

Since there is no specific up to date information published, the databases of the breast pathology unit of Hernán Henrique Aravena Regional Hospital were accessed, which allowed to have a specific epidemiological background of the region (2).

(2) Information obtained from the database of the Breast Pathology Unit of Hernán Henríquez Aravena Hospital in Temuco, for academic use only.

Table 1. An epidemiological background in the region of Araucania, Chile.

Source: Own elaboration.

From the foregoing, it is clear, for example, that for the last 3 years 728 new cases of breast cancer have been presented in the region. This means that 22% of new consultations in the last 3 years result in a diagnosis of breast cancer. One of the reasons that explain this progressive increase corresponds to early detection policies.

Statistics coincide with the data at the national level, according to which there is a “25.2% of cancer incidence in this group” (Icaza, Núñez and Bugueño, 2017). Likewise, the lack of more detailed and accurate information is ratified, according to the type of information that was obtained for these data.

Now, if we consider only the 716 new consultations from the first half of the year 2019, 128 correspond to new cases of breast cancer. Of the new consultations, 106 cases correspond to women up to 35 years, seven of which resulted in a diagnosis of breast cancer. Of the remaining 610, 121 correspond to cancer cases. Between 36 and 70 years, cancer cases are 97 out of a total of 548 new consultations in this age group. Above 70 years of age, there are 62 new consultations, of which 24 were diagnosed with cancer.

Thus, we can see that up to the age of 35 years, the number of consultations is low, since it represents only 15%, whereas in this age period the consultation could turn out to be early, obviously depending on the characteristics of the cancer. This could also be associated with less concern.

Moreover, between 36 and 70 is concentrated 77% of consultations, with 18% of cases diagnosed that result in cancer , but this group, at the same time, represents 76% of total cancer cases during the first half of 2019. The above implies the need to focus on clinical and communicational work (health promotion) in this age group, considering their social and cultural particularities.

In this sense, not only are the statistical correlations that have been made interesting, but also the narratives of the women themselves. The interviews conducted so far, account for some narratives of special interest for the work. We will understand an interview as “a systematized conversation that aims at obtaining, retrieving and recording the life experiences stored in people’s memory [with] an informative richness in words and interpretations” (Sautu et al., 2005, pp. 48 and 49).

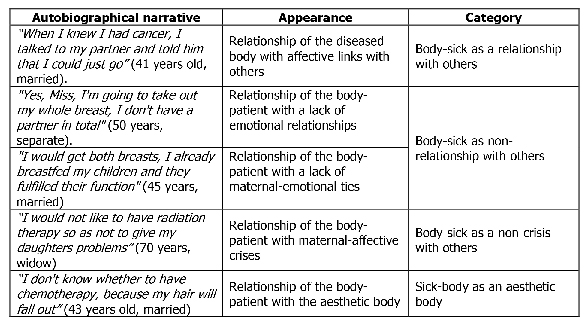

Below we will cite some examples, as part of the type of analysis corpus that will be used, corresponding to certain autobiographical narratives of women expressed in the interviews (3):

(3) Quotations extracted from clinical interviews with patients at Hernán Henríquez Aravena Regional Hospital, identity reserved for bioethical reasons; being only for academic use.

“When I knew I had cancer, I talked to my partner and told him that he could just go” (41 years old, married).

“Yes, Miss, I’m going to have my whole breast removed, I don’t have a partner anyway” (50 years, separate).

“I would get both breasts removed, I have already breastfed my children and they have fulfilled their function” (45 years, married).

“I would not like to have radiation therapy so as not to give my daughters problems” (70 years, widow).

“I don’t know whether to have chemotherapy, because my hair will fall out” (43 years old, married).

These examples refer to several aspects that will be used as categories for the research work of the thesis, namely

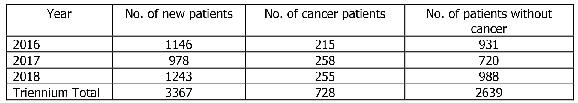

Table 2. Autobiographical narratives of women with cancer.

Source: own elaboration.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Considering the statistical data, which allow epidemiologically locate the problem, it is intended to further deepen the social and cultural characteristics of women of both age brackets worked here, namely up to 35 and between 36 to 70 years, through focused and in-depth interviews; This will make it possible to understand the incidence of women’s relationships with their body in the motivation for consultation and treatment.

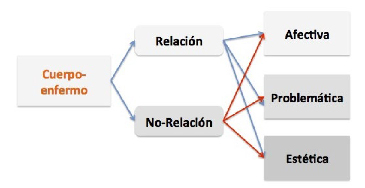

Meanwhile, the results of the analysis of autobiographical narratives of women account for those critical knots that from their auto-representations allow establishing how the way of understanding the sick body can relate empirically with how the disease is treated.

While the examples used here are only paradigmatic and casuistic, they allow for a basis for further progress in theoretical discussion and methodological design.

For now, we see relationships of the sick body:

Source: own elaboration.

Image 3. sick-body relationships, according to narratives.

REFERENCES