doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2020.51.63-82

RESEARCH

PROPOSAL FOR SPEECH DRIVEN BY THE DELEGATION OF THE GOVERNMENT FOR GENDER VIOLENCE. ANALYSIS OF A REFERENCE DOCUMENT FOR PROFESSIONALS

Propuesta de INTERVENCIÓN IMPULSADA POR LA DELEGACIÓN DEL GOBIERNO PARA LA VIOLENCIA DE GÉNERO. ANÁLISIS DE UN DOCUMENTO DE REFERENCIA PARA PROFESIONALES

PROPOSTA DE INTERVENÇÃO IMPULSADA PELA DELEGAÇÃO DO GOVERNO PARA VIOLÊNCIA DE GÊNERO. ANALISES DE UM DOCUMENTO DE REFERÊNCIA PARA PROFISSIONAIS

Encarnación Aparicio-Martín1. Complutense University of Madrid. Social teacher and teacher, specialist in Detection and Intervention in Gender Violence and expert in Equal Opportunities, PhD student and collaborating professor at the Complutense University of Madrid

1Complutense University of Madrid. Spain

ABSTRACT

This work has carried out the analysis of a speech guideline proposal with women victims of violence gender, driven by the Delegation of the Government for Gender Violence and for professionals. From a critical discourse analysis, the work aims at making visible the re-victimizing framework from which the intervention against gender violence is approached. It also aims at highlighting a lack of rigor spread to key processes that make up what should be a professional care and that inevitably impacts people likely to need such attention. Consequently, the simplistic and reductionist conception that underlies Social Intervention and that devalues both it and its professionals (women for the most part) can be verified. Understanding the document as an institutional discourse production, it serves as an example of the state of affairs. This paper points out the need for improved speech before the violence of gender and also some of the invisible mechanisms that support the structural and systemic nature of inequality, such as the individualization of the social or the prospect of scientific professional- devaluation - of Social Intervention and, with it, of the disciplines involved.

KEY WORDS: social intervention, violence of gender,professional practice, discourse analysis, socio-critical paradigm, vulnerability, inequality

RESUMEN

Este trabajo ha llevado a cabo el análisis de una propuesta de pautas de intervención con mujeres víctimas de violencia de género, impulsada por la Delegación del Gobierno para la Violencia de Género y dirigida a profesionales. Desde un análisis crítico del discurso, el trabajo tiene como objetivo visibilizar el marco revictimizante desde el que se aborda la intervención ante la violencia de género. También pretende evidenciar una falta de rigor extendida hasta procesos clave que conforman la que debiera ser una atención profesional y que, inevitablemente, impacta en las personas susceptibles de necesitar dicha atención. Consecuentemente, se puede constatar la concepción simplista y reduccionista que subyace de la Intervención Social y que devalúa tanto a ésta como a sus profesionales (mujeres en su mayor parte). Entendiendo el documento como una producción discursiva institucional, sirve como ejemplo del estado de la cuestión. Este trabajo señala la necesidad de mejora de la intervención ante la violencia de género y también algunos de los mecanismos invisibles que sostienen el carácter estructural y sistémico de la desigualdad, tales como la individualización de lo social o la perspectiva de desvalorización científico-profesional de la Intervención Social y, con ella, de las disciplinas implicadas.

PALABRAS CLAVE: intervención social, violencia de género, práctica profesional, análisis del discurso, paradigma sociocrítico, vulnerabilidad, desigualdad

RESUME

Este trabalho tem a finalidade de analisar uma proposta de pautas de intervenção com mulheres vítimas de violência de gênero, impulsada pela Delegação de Governo para a Violência de Gênero e dirigida à profissionais. Desde uma análise crítica do discurso, o trabalho tem como objetivo visibilizar o âmbito de re-vitimização diante da violência de gênero. Também pretende evidenciar uma falta de rigor estendida até processos chave que conformam na que deveria ser uma atenção profissional e que, inevitavelmente, impacta nas pessoas suscetíveis de necessitar tal atenção. Consequentemente, se constata a concepção simplista e reduzida que subjaze na Intervenção Social e que desvaloriza tanto à esta como a seus profissionais (mulheres em maior parte). Entendendo o documento como uma produção discursiva institucional, serve como exemplo do estado da questão. Este trabalho assinala a necessidade de melhorar a intervenção diante da violência de gênero e também alguns dos mecanismos invisíveis que sustem o caráter estrutural e sistêmico da desigualdade, tais como a individualização do social ou a perspectiva de desvalorização científico-profissional da Intervenção Social e, com ela, das disciplinas implicadas.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: intervenção social, violência de gênero, prática profissional, análises do discurso, paradigma sócio-crítico, vulnerabilidade, desigualdade

Correspondencia:

Encarnación Aparicio Martín: Complutense University of Madrid. Spain.

e.aparicio@ucm.es

Received: 14/05/2019

Accepted: 02/07/2019

Published: 15/03/2020

How to cite the article:

Aparicio Martín, E. (2020). Proposal for speech driven by the delegation of the government for gender violence. Analysis of a reference document for professionals. [Propuesta de intervención impulsada por la delegación del gobierno para la violencia de género. Análisis de un documento de referencia para profesionales]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 51, 63-82.

doi: http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2020.51.63-82

Recovered from http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/594

1. INTRODUCTION

This proposal, as stated in the document itself, was “driven” by the Delegation of the former Government to Gender Violence (from the Ministry of Social Services and Equality of the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality) and continues in effect from the current Government Delegation for Gender Violence (from the Ministry of State and Equality of the Ministry of the Presidency, Relations with the Courts and Equality) (1). Despite not having updated the ownership of the document, it is accessible and defined as “action protocol” placed within the “comprehensive social assistance” in the section aimed at “professional” and which is described as “section to provide information and exhaustive materials to the different professional fields involved in gender violence” (2).

(1) The only data that has been known about the edition and publication date is the year mentioned in the hyperlink of the same name that gives access to the document: “Proposed guidelines for comprehensive and individualized intervention with women victims of violence of gender, their sons and daughters and other dependents (2014).pdf”. It was located on the official website of the Delegation for Gender Violence of the Government at the time, and is still accessible on the official website of the Delegation of the current government.

(2) Ver: http://www.violenciagenero.igualdad.mpr.gob.es/profesionalesInvestigacion/asistenciaSocial/protocolos/home.htm [Date of consultation: April 30, 2019].

The fact this document has been presented, and it is still presented, institutionally, as a professional performance protocol to provide a comprehensive care to the surviving victims of gender violence, gives it relevance and makes it susceptible to analysis. This one could also be understood as a methodological, multidisciplinary tool of ethical-political character, therefore, it could have, and in fact, it has a great impact on the lives of people.

2. OBJECTIVES

This work, in a broad sense, tries to contribute to the awareness of the political dimension of Social Intervention and, therefore, of the responsibility that various professions involved assume from their practice. The study also aims at showing how the scientific-professional nature of Social Intervention can be veiled; the reductionism to which it is subjected and, therefore, the damage that this may entail, not only for the people and groups involved in this area but for society in general.

3. METHODOLOGY

This article, as a critical dialogue with the document studied, and from an interpretive perspective, presents questions and points out elements for reflection. Following the fundamentals of the Critical Analysis of Discourse collected by Martin Rojo (2003) arguably, this paper presents some elements of textual practice, the discursive practice and social practice that emerge from the document. The focus is not only on the organization and on format of the informative content, but also on the forms of construction of certain representations (status, condition, function, relationship, etc. of/between different agents and processes) since the implicit incorporation of conceptions, attitudes and values.

As for the structure of work, the article consists of two sections: the first one presents the perspective of analysis, and is dedicated completely to rescue, from a socio-critical paradigm, centers of interest, especially on Social Intervention, picking up the thought of experts in different disciplines; the second, yet also including some reference to the thinking of experts, focuses on the analysis of the document, trying to keep as much as possible its structure o and the nomenclature of its sections, since these ones are also subject to comments .

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Analysis perspective

From the Social intervention as practical action aimed at solving social problems, it “is conceptualized as a form of activity that integrates political, philosophical aspects (...). This doing is linked with theoretical and technical knowledge, but especially with attitudes, values and beliefs that put ethics before the action” (Saavedra, 2015, p. 137). However, the intervention is not defined by demand; it does not escape the historical, symbolic, conceptual, social framework of the person who intervenes, and who is the one that ends up characterizing -if not determining- the type of intervention that is carried out. Intervention can never be aseptic; it is still the political commitment, and the design, that the funding agencies and auditors make of the social order (Cuenca, Sánchez and Burbano, 2014).

This contributes to a double confluence of opposing currents. On the one hand, taking the perspective of Epstein (Zamanillo, 2012) to the current Spanish context, there is, intrinsically, a kind of disharmony -if not incongruity- since openly and mostly it acts to get people to adapt, adjust to the social order established while, at the same time, supposedly, it is intended to activate decision-making, creative, critical thinking, even in certain areas (such as the one this work focuses on) radically challenging towards hegemonic models: a thought that allows transformation. On the other hand, it is considered that, extrinsically, a type of inconsistency arises that is visible as a principle request, requiring, for example, as a prerequisite for access to a service, or initiation or continuity of a process, what would just have to be achieved from said service or process, conformer of the intervention process itself.

In this context, it is also essential to remember that a process defined as protection, accompaniment, help, inclusion, care, empowerment, etc., and that is being carried out from the public administration or from the sphere of solidarity, does not exempt it, in any way, if rigorously evaluated, it cannot be exempt from scientific or ethical analysis. The threat of “adiaforization” must be fought again (using the concept of Bauman), the apparent permanent effort to:

place, on purpose, or by default, certain acts and/or omitted acts with respect to certain categories of human beings (…) outside the scope of the phenomena subject to moral evaluation; stratagems to declare those acts or that inaction, implicitly or explicitly, as “morally neutral” and prevent the options among them from being subject to an ethical judgment (...) (Bauman and Donskis, 2015, p. 57).

On the other hand, when individual answers are required to face and solve problems socially created (Beck Bauman, 2009), it is people who are blamed exclusively for those difficulties they are facing (Bauman 2009; Giroux, 2015), so this way they are subject to systematic judgment on its worth: its resources, skills, self-reliance and self-control. Professionals are holding this perspective, among other reasons, because they are being instructed from/for it. Zamanillo and Martin expose the lack of “critical global thinking” among professionals and intellectuals, and denounce how in which should be an ‘ethical-political project”, however drift towards partial interventions –individual and family have taken over training [in Social Work studies]. Silence on the structural factors that produce and reproduce inequality, poverty and social exclusion is alarming” (2011, pp. 102-103).

Regarding the approach to gender violence, just to highlight in this section that the Declaration of the Ombudsmen issued last October (2018, p. 2) considers in its fourth point that: “specialized centers (…) require of improvements in operation and design (…)” ; from the fifth point it is recommended that: “training and awareness should be reinforced in the field of gender violence of all personnel involved (….) through specialized, continuous, compulsory and assessable training (…)”, and in its eighth point suggests: “the improvement of the quality of public services for comprehensive care (…), as well as the incorporation of techniques for the evaluation of public policies, for which a specific annual inspection plan has been developed and executed”.

Regarding the relationship between discourse and society, remember -following the ideas of Van Dijk (2002)- that discourse builds, defines, changes social structures; its structures speak of or represent parts of society. Its role is crucial in social cognitions. “Discourse has ideological implications. (…) Discourse is a form of social action”. (Fairclough and Wodak in Van Dijk, 2016, p. 205). In Social intervention practice, this is translated into asymmetries and, and as explained by Martin Rojo, to the benefit or detriment of the interests of certain individuals, groups, communities, because discourse can create “a representation and no other events, and this in turn will reinforce or question, naturalize or object to visions of events and social order and not others, some ideologies and not others” (2003, p. 164).

On the other hand, Zamanillo makes clear that in the so called helping professions, the analysis of relationship spaces has been given up, and the main reason is, according to this author’s experience in:

The so evident denial of theory as intermediation with practice. (...) and the disdain for theory makes it impossible to recognize the powerful ability of analytical categories to name otherwise the facts, relationships, contingencies and phenomena that surround us and that we face. And name them otherwise is to look at them differently, a look that will help us intervene differently (2012, pp. 158-159).

Therefore, interlacing theory and practice is the only way to effectively achieve a certain amplitude in the eyes that allows to be aware of the complexity not only of violence of gender or other social problems, but the social intervention before them, or -at least- of the reckless, pernicious, simplification of it.

4.2. Analysis exercise

“Proposed guidelines for comprehensive and individualized intervention with women victims of gender violence, their sons and daughters and other dependents” (3)

(3) In an attempt to respect the structure of the document studied, the nomenclature and order of the parts analyzed are maintained - as far as possible. The format of capital letters in the different epigraphs is not conserved nor when reproducing parts of the text to facilitate the reading and not to mislead with respect to the structure of this article.

Framework

The premise from which it starts is that this is a document of reference aimed at professionals since, as stated in the fourth paragraph of this section, the Delegation of the Government or Gender Violence: “drives this proposal that contains guidelines and minimum elements that could be taken into account in the comprehensive intervention aimed at women victims of gender-based violence”, and which in the following paragraph is presented as: “guiding frame of reference for all professionals who with specific training and supervision, carry out their work in the different networks of specialized resources, residential or non-residential (…) for women victims of gender violence and their children”.

Proposed guidelines? Guidelines and elements? “Minimum” guidelines and elements that “could be taken into account”: That is, not necessarily. Which ones can be dispensed with? Are they minimal, but it is not necessary to take them into account? Framework of “guidance reference”: Reference. But indicative. “Professionals with training”: Professionals of what? With training? What training? Is it possible that there is a circumstance that the intervention is carried out by unskilled personnel? “Specific supervision”: Supervision? Specific? Who supervises? Who does this document question? Do you have another document exclusively for those who supervise?

This set of questions already shows that, from the format and the writing to the terminology and the sequencing of content, all this will inevitably lead to a context of informal, lax, ambiguous, inconsistent action. On the other hand, the document does not consider the inclusive language as necessary since the same text does not apply it. It uses the generic masculine several times when referring, for example, to “all professionals” and later to “a professional reference”, although being a work aimed at addressing the violence of gender (maximum exponent this one of equality) and that the vast majority of the professionals working with women victims - survivors of domestic violence are women. You can also read “of the child”, “children” or “sons or daughters” despite that N predates the R and it could be written sons or daughters.

It refers to the Reference Catalog of Social Services and the common criteria of quality and “good use -solidary and responsible- for services” in the second paragraph of the first page of the documen5 (4).The use and position of this message in the text denotes a prioritization that reveals the underlying prejudices. Beyond the re-victimization that could mean that the rights would be turned into privileges, it is expected to remember that it is intended, as the document itself recognizes -a “comprehensive” care that often requires a basic need cover to ensure protection or even the crisis intervention, among many other performances.

(4) The page number is established by the author of this article since the published document is not paginated nor has any index.

Beyond the frequent injuries that physical violence entails and even disabilities such as deafness or loss of vision, and many other serious damages that violence has at its base, such as fibromyalgia and irritable colon, those problems qualified as of lesser severity cannot be forgotten, such as (gastrointestinal, headaches, musculoskeletal pain, among others) bring, without a doubt, a significant deterioration in the quality of life of those women who suffer from them. There are also frequent damages to sexual and reproductive health (STDs, sexual dysfunctions, gynecological problems and in pregnancy) and, in a significant percentage, autolytic attempts and suicidal ideation are present. On the other hand, the consequences of violence are chronified and transcend abuse; traumatic experiences bring a deeper vulnerability, suffering (Matthew and Good, 2018, pp. 57-59). Among the psychosocial consequences, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem, post-traumatic stress disorder, attention deficit and concentration deficit, hyperactivity, inhibition and isolation, risk behaviors, learning and socialization difficulties and trans-generational violence can be highlighted with high tolerance to situations of violence, among others (Aretio, 2018, p. 75). That is to say, it is very far from presenting, for example, a tourism program (without trying to subtract all the respect it deserves).

The fourth paragraph states that “in order to promote instruments that guarantee the sufficiency and quality of personalized and multidisciplinary intervention (...) this proposal is promoted”. However, sufficiency (5) is not an element that adds to the concept of quality; at least in the context that concerns us this would be completely non-existent without it. To point out the pleonasm used to obviate the meaning of the concept of quality and turn a sine qua non condition into a merely desirable element. It seems to be that there is the possibility of offering insufficient service, so the underlying idea is that attention is dispensable. Again, a right turned into a privilege.

(5) According to the Dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy (DRAE), “sufficientia”, from Latin, means “capacity”, and as an adverbial phrase, “quite”.

The claim of the document is “that women victims of domestic violence (...) enjoy similar common conditions and criteria in their care”. We must highlight the connotations of using the verb “enjoy” (instead of “dispose”, for example) when referring to the conditions of attention. It is again revealing that a term that evokes delight is chosen, which constructs an imaginary of pleasant activities.

Purposes

In the section “ends” in the first paragraph, is used the expression “Giving them the opportunity to move away from the focus of gender violence”, rather than make it possible, which would probably be more successful, for instance. First “you enjoy the conditions”, and now “the opportunity is given”. Again, it is a privilege, not a right. As for getting away from the “focus of violence”: Focus? Is violence exercised by an institution? ¿Something abstract that cannot be named or defined?

At this same point, it is established as the purpose “To guarantee (...) qualitative accompaniment”: just to say that it has not been possible to understand what the document refers to with this expression; Perhaps it would have been easier if an example of only “quantitative” accompaniment had been found.

Beyond a space and time for “emotional” recovery (it seems that only this is necessary, and there would be no more damage that lasts), the need for “awareness” is specifically specified, without greater precision. What is awareness? This lack of precision invites to think that it might be assumed that the idea the mere fact of being victim- survivor of gender violence, one is systematically, in a state of unconsciousness widespread ; In fact, a few lines later the text states as one of the purposes: to promote “responsibility”. To which professionals is this text directed, specialists in what disciplines? What is the concept of gender violence? Are women “victims of violence gender” a collective? On the other hand, even from responsibility as the ability to respond, does this not have somehow a link with the capacity to respond of the environment?

It is necessary to note also the reductionism that involves identifying violence of gender victim survivor with a person in difficult socioeconomic situations; to emphasize “especially” in the “insertion and job training” (with these terms and not others) seems to give proof of this. Even if we do not forget that - as UNO Women (2015) explains - women who have been exposed to violence are at greater risk of experiencing difficulties in employment, homelessness and, in general, social isolation and poverty, it is certainly pernicious understanding the surviving-female victims of violence of gender as a collective, and ascribing specific characteristics, obviating what is also argued by the agency cited above: that at the risk of violence there are no fixed characteristics or inherent in certain people or groups; “Women across the social spectrum suffer violence and there are many factors that contribute to their perpetration” (UN Women, 2015, p. 19).

The last of the purposes “in relation to women” that the document states is: “To support women (…) so that they can abandon their position as victims”. This suggests, at least, that the emphasis is placed on the attitudinal and, therefore, it could denote certainty or judgment, since position is chosen as opposed to situation. In addition, there are serious doubts about the use of the verb “leave” since, taking into account the overall tone of the document, it invites us to think that, again, it all starts from the notion of co-responsibility for the “Initial position” (chosen and preserved), something to be renounced, to be left (6); It would not be far-fetched to think that this expression of “abandoning their position as victims” only blames them.

It should also be noted that, in the document (at least in the sixth point of this section) it is decided to refer to women as “the host woman” even though the document does not specify that it is a proposal of guidelines for intervention exclusively aimed at residential resources, or “foster homes” (which is the nomenclature to which the text here evokes). In any case, even in such a residential context, the women (are not) (7) are in a situation of protection.

(6) According to DRAE, the first three meanings of “abandon” imply “stop”. The first meaning of “position” is: “posture, attitude or way in which someone or something is placed”.

(7) Even focusing on a residential resource, and focusing on the situation of “social risk”, women are not “foster women”, in any case “they are in a situation of reception”. In any case, the criterion for accessing a residential resource is, in principle, the “vital risk”, regardless of whether social risk could also occur. Therefore, we must speak of protection, not so much of welcome.

“In relation to children and other persons dependent on women” (or as one could refer to the latter: dependent persons) the document insists on giving “the opportunity” to get away from “focus” of violence, and proposes in the third point “to provide through attention and comprehensive approach to all their needs (psychological, social, educational, legal) an environment to grow and develop, while performing social responsibilities that corresponds to them according to their age”. Beyond the fact that the thought seems to continue to be set on the residential, again the opportunity to refer to the “responsibilities” that befit them according to “their age” is not wasted. “Performing at the same time social responsibilities?” This expression serves as an example of the writing, use of concepts, etc., which occurs both in this section and in the rest of the document.

I. Admission to the resource (8)

Elements to consider and objectives

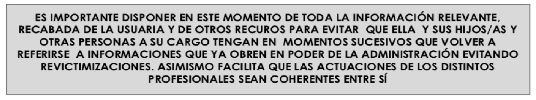

Beginning by pointing out that the term “admission” raises many doubts, but what is completely incomprehensible is a section called “elements to consider and objectives”. This is another example regarding the technical level reflected in the document and, therefore, the lack of professionalism with which this issue is being addressed. We should point out, within this section, the text with letters in bold and capital letters inside a box colored in gray, as an alert or reminder, is located at the bottom of the page.

(8) At this point in the document, (It corresponds to a third page) the title of the document framed at the top of the page appears again. It is decided to avoid reproducing it considering that it could lead to error.

Having “all” the “relevant” information “facilitates” that the different actions are “consistent”. Once again, the question arises: To whom is this text addressed? To professionals? Perhaps it is being taken for granted that it is important to remember this. If so, or it is being assumed that they are not qualified, or rather they may not be able to intervene in/from the conditions that the situation require. In any case, it appears that both situations can be assumed naturally since a gray box with text in capital will be enough help.

In the second paragraph it is explicit (it cannot be deduced whether as “element to take into account” or as “targe”) “women should be informed” about “performance standards” of the resource most suited to their needs; In the fourth paragraph, it was also explained that a document explaining rights, “duties and obligations” and “operating regulations” of the resource in which they are must be provided. Are there really no other “elements to consider and objectives” that deserve space in a document like this, of reference, and that can contribute more to the intervention? Is it really imperative to prioritize this and insist on reporting duties, obligations, and regulations?

The wording of the sixth point deserves to be reproduced in full: “To support the user and the family unit admission to the resource creating a climate of trust and empathy conducive to create links with the resource team without creating expectations and unrealistic needs”. To support admission? And explain “elements/objectives” such as empathy?, we insist: who is this document for? Lastly: “without creating unrealistic expectations and needs?”

In the eighth point it is literally indicated that raised expectations and needs “assessed and collected” To evaluate and collect? “To further define the objectives by areas that should counted on the individualized action plan (IAP)”. “Or objectives by areas that should be included in the plan (…)”. To finish this section, in the last point it is urged to establish “a date for the development and evaluation of the Individualized Action Plan (IAP)”. There is no distinction between “elements”, “objectives”, “to evaluate”, “to collect”, but it is important to establish a date.

II. Evaluation and intervention: Formulation of the individualized action plan (IAP)

To begin by pointing out that the established structure cannot be understood: The first section is devoted to “admission”; the second one to “Evaluation and intervention: formulation of the IAP”. In addition, the wording of the text leads to think that the man has his eye permanently on a single type of resource (Residential), which implies even greater reductionism and evidence that the devaluation and non-professionalization of intervention are especially significant in this type of resources and contexts.

The IAP is described as a “document”, “a document that should serve as a guide throughout the intervention”. It is explained that “it places women and professionals throughout the intervention process, allowing them to keep track of the clearly defined objectives agreed with women”. Again, an example of laxity (to use a euphemism) that presupposes it could get to be. Again, there are only two questions to be asked: who is this document for? What type of intervention is assumed that could be performed or being performed?

Neither in the preceding paragraphs, nor in this one, no space is devoted to the evaluation. There is just a sidelong mention, for example, to “assess and collect expectations and needs” and “set a date for the development and appropriate periodic evaluations of the EPI”. It could also rescue its link with terms such as “assessment”, “diagnosis” and expressions such as “accredited initial compliance with the objectives”, “review the EPI compliance” (9) or the references in the different areas to the “monitoring” of the PAI, specifying that its implementation “desirable” (not necessary either, therefore) (10) and it will be “based on the period of permanence of women in the resource”. There is no more mention of any evaluation process, nor in isolation to any of the criteria that could conform it. With respect to that desirable follow up, depending on the permanence, it is not even understood exactly what the approach is: ¿Intervention depending on “continuance” and not “continuance” depending on the result of the intervention?

(9) These two expressions are found in the third section “Outcome / Registration / Follow-up”, which has a single subsection called “Elements to Consider and Objectives”.

(10) That the “follow-up” of the IAP is “desirable” opens the door to an activity (not even defined as care) that is far from being considered serious, even less professional, even less quality. This is another example of how this document contributes to offer a simplistic and reductionist idea that only dishonor the professional sector of “Social Intervention” and with it the scientific disciplines involved in it and the competencies and performance of its professionals.

Elements to consider and objectives

In the first point it is suddenly mentioned Individualized “Attention” plan (we understand it as synonymous with the previous Action Plan). Meanwhile, women go from being “women” to “users” or “woman” or “user”. Another example of the lack of precision in the drafting of the text and, therefore, the lack of rigor that shows the entire document. As for the rest of the section, it is presented as a brainstorm. It can be defined as a botch job that mixes processes, levels, areas, etc., and (even if it saves logically certain “elements to consider and objectives”) it suggests a perspective about women “victims of gender violence” as a collective, it seems to be that they have common specific characteristics such as the tendency to irresponsibility and dependence.

If you want to make a diagnosis, “avoiding pathology”, why is the term treatment used later? Is it like this that pathology is avoided? On the other hand, it is not urged to ensure the conditions that facilitate emotional recovery, but just to “promote the recovery of the emotional damage” and the most surprising thing: this “promotion” remains at the same level as the coordination of “meetings: internal and external coordination (…) and the establishment of the referral mechanisms that are required (…)”. Coordination meetings “that facilitate professionals to orient the established objectives in a clear and congruent way with the intervention to be carried out and the mission of the resource”: To orient the objectives set?, To guide the objectives clearly and congruently with the intervention you want to perform? To orient the objectives with the mission of the resource?

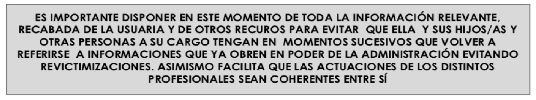

Note, too, that at no time the possibility of training in feminism, or education for equality, seem to be contemplated (11) (just something more subtle, “to facilitate knowledge and skills”). But what could be considered serious, without a doubt, is the absence of the term “empowerment”, especially whereas there is no hesitation while moving -as colored main message and with capital letters that should be motivated for “the treatment”. There are no more comments on the colored text that stands out as an alert or reminder at the end of the section:

(11) It should be noted that, paradoxically, the educational term is usually avoided, probably because it is being assumed the harmful and widespread idea that it implies an infantilization, however, it is not a problem to assume the risk of psychopathology or medicalization.

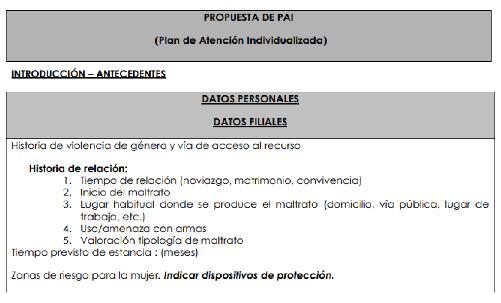

ICP Proposal (Individualized Care Plan) (12)

(12) At this time the IAP is once again defined as a Care Plan and not an Action Plan. The structure presented is so incomprehensible that it is decided to include the full image of the title and the first section.

More emphasis is not going to be put on the difficulties found in understanding the structure, nor expressions such as “Introduction-Background” or itself around the section “Relationship history” (elements that make it up and omissions). Influence that it is only requested to specify the planned time of stay “(months)”, that is a document entitled “Proposal of guidelines for intervention: Comprehensive and Individualized with women victims of gender violence, their sons and daughters and other people they are in charge with” that includes an “Action/Care Plan Individualized” that starts at a time scheduled, (and also of no intervention, care, support, advice, support or participation, etc.): of stay. What specific resource is being thought of? What resources, interventions, previous information are presupposed? What professionals previously involved? Where does one start from?, Where does one want to go? One could continue asking questions infinitum ad.

After the section called background- introduction, there are sections coincident with the areas : “socio-educative ” of social, legal, psychological work, (this is divided into two subsections: women , and minors, and/or persons in charge of them) and, finally, the area “educational for children”. In all of them, at the beginning it is explained that “the information that is considered important to collect in the area is shown”, “from the different resources that work with the woman and their children”. And at the end of each area the following text is repeated:

That is: on the one hand, now it is explained to the professionals the Information, “which is considered important to collect” from “other resources” and on the other hand, it proposes the development or establishment of what might be politely defined as a tidal wave: “Objectives: commitments, actions and monitoring”. The evaluation of the intervention still has no luck finding its space, not even randomly. Nor it is clarified the criteria to choose “information” and, regarding the various areas, it only should be noted that, in the best case, as indicated in the document, it picks up some collection of data. From here there is no possibility of further analysis since, again, it is about brainstorming groups, or lists. In this section, the content, in some areas such as the “socio-educational” and “educational for children”, are remarkable for its emptiness and lack of structure.

The document effectively equates an “Individualized Care Plan” with a data collection. Just remember Zamanillo when he claims to transcend lists of facts or problem situations in the analysis of reality, while insisting on the need to have knowledge that allows to conceptualize: “without concepts we are blind because it is the act of naming which creates realities and research objects, not the mere relation of data of the realities that make up the world in which we intervene” (2012, p. 166). We also have to point out the pernicious of identifying “objective” with “performance” and “evaluation” with “diagnosis”. And, finally, to insist on the impact of reading again and again in each section corresponding to the different areas: “The objectives are set in a short term since it would be desirable to monitor the IAP based on the period of continuance of the woman”.

Assessment and conclusions

You can only repeat but questions such as: Assessment and conclusions? Important to avoid “hasty conclusions?” To avoid “hasty conclusions in the definition of objectives?” “To adjust female user’s expectations with the objectives?”

Just to finish the section aiming at the individualized care plan, it is included what could be seen as one example of how it should be formalized the plan: the signature of the “directorate of resources”, of the “Technical team” and under these ones, the signature of the “Resident/female user”. Apparently, the document considers essential to dedicate a space to instruct in the signature of the IAP.

III. Output/Registration/Follow up

Elements to consider and objectives

It is not possible to understand how one can “conclude the intervention process once the initial fulfillment of the objectives is accredited” (as explained in the first point of the section). Complied initially? In turn, the second point is raised again as an example of technical quality: “To review the compliance of the IAP, by assessing objectives met and possible difficulties”. To review compliance by assessing objectives met? and something less surprising: “To train the surviving woman to serve as a support and example in the recovery of other women”. It emphasizes, on the one hand, the use of “survivor” (for the first and only time in the document) and, on the other, the explicit purpose of getting women to serve as support, and as an example.

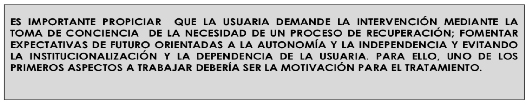

In general, the whole section is still another brainstorm, between simplicity and inaccuracy; in fact, it is called: “Output/registration/Follow up” and its shallowness is reflected in points such as the ones pointing out the need to agree guidelines to follow up with “the client” or establish a monitoring system to “see the evolution of the woman”. The message that is highlighted (using the usual text box format colored in gray and with capital letters) is as follows:

Again, the choice of language denotes a very concrete perspective that looms at the point of departure (again, from a specific resource and in front of very specific needs) and in what is proposed in this respect. What does “appropriate material conditions” means exactly for output/registration? Is it important to facilitate?, To make it easier that they can have employment and housing? It is not essential, there is no need of guarantee; it is only important to facilitate them... That is: permissive of exclusion, if not actively exclusive. And, in addition, not because it is a right but because “it helps to avoid institutionalization or referral to another resource”. In fact, already in the section dedicated to the formulation of the individualized action plan, it was pointed out, in the colored note, the importance of “fostering future expectations oriented towards autonomy and independence, avoiding institutionalization and dependence”. This notion is well expressed, it takes us back to the Victorian charity; referring to Octavia Hill and the movement of “friendly visitors” Walkowitz explains: “They had to offer spiritual help and discipline” tenants who, for lack of will, need permanent momentum under pain of being left irretrievably behind” (Miranda, 2009, p. 105).

Also note that this limit to “facilitate” does not correspond to the first point of this section: “To conclude the process (...) providing the user with the resources and support necessary for their autonomous life” (it can be seen that the document ends as it begins: at the beginning it reminds us that there should be a solidary and responsible use of the resources, and in the end it insists that the referral to another resource should be avoided).

Since the document once again focuses on employment, mentioning, in addition, the right to housing, “To facilitate”, not to guarantee, evidences, as already mentioned, not only the requirement of the ability to individual response, but also the permanent exercise to hide deprivation as a rate to define poverty (13), and also to make invisible the true scope of social exclusion. Getting support in the work of Gordon and others, Giddens and Sutton recall four dimensions of social exclusion: besides poverty or exclusion of income or adequate resources and exclusion from the labor market, also excluding services and exclusion of social relations (2013, p. 623).

(13) It seems to be that from that special mention that in the document refers to training and employment, the objective of “facilitating” access to housing is already covered (however, in Spain today neither training guarantees employment, nor a fulltime job guarantees the possibility of covering accommodation and maintenance , even less it ensures access to decent accommodation , even less suitable for a family with any special needs arising from such a complex and devastating process like violence of gender. in any case, there is no doubt that we have passed from welfare to workfare (see Rodriguez and Díez, 2018) where universal rights are contingent upon the achievement of certain productivity, not any successful within the working market.

In short, when it is not about strategy, but about program (to the point that even care time -and with it needs- they can come default), when the goal is to “facilitate” resources, at best cases, and not to guarantee rights, when the greatest effort is put -from a homogenizing perspective- to make the person “fit” in the “aid” system, he/she becomes the sole protagonist, and the agent of said process, and not people. A “discipline technology” that allows to control behaviors, attitudes, aptitudes, to improve performance, put the person where he/she is most useful (Foucault, 1993, pp. 58-59). Or where he/she least hinders.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Beyond the lack of methodological rigor, and even the approach underlying, where the intervention with women victims-survivor of gender violence and approaches much closer to control dynamics -if not imprisonment, and medicalization- than to their empowerment, and in which the rest of people for whom it is referring occupy a residual place, it is worth noting the damaging nature of one document that chooses to explain to then professionals issues that appear to be likely to be forgotten by them, such as the need to achieve “an environment of empathy”, “to review the individualized action plan based on new needs or circumstances” and “to obtain informed consent from the user for the processing of their data”, among others.

From the conversion into a mere functional knowledge of the corpus discipline involved, and intervention practically reduced to resource management, batiburrillo, frangollo are some of the terms that from here it is considered that could be used to define what is displayed as one of nebula report. Inappropriately are called “intervention guidelines” a whole mess of vague, ambiguous, and even incoherent slogans like a brainstorming session. This is materialized in a document that is estimated, at least, improvised: it is far from being an instrument that guarantees the quality of the intervention and an “individualized action plan”, and in which, on the contrary, to unite, equate, juxtaposing and/or combining system, program, phase, character, type, objective, purpose, etc., randomly, is a leitmotiv, and this is joined by alarming reductionisms, significant omissions and vexatious reiterations, among other endless objectively minimized issues.

The document could not be described as technical, professional. Even less it can be considered useful as a “reference” for professionals. In any case it depends, of course, on the image and concept that is available in the sector/sectors in which could settle intervention and disciplines and professionals to which and whom could be alluded directly or indirectly, or that could be referred to. This document is a great example of how an attempt of regulation can achieve the opposite effect to the one desired. This document not only should be defined as technical, but should be understood as a strategy of non-professionalism (curiously in a female sector); not only does it not contribute to a quality intervention, it also hinders it. Social intervention cannot be frivolous, nor a simplifying image of its complexity can be transferred, and this document does so.

The rights turned into privileges, the calls to the responsibility of, -surviving victims and the constant appeal to control mechanisms, leads us to a focus of suspicion, even punitive (if not openly for the situation that is being faced, indeed for the risk that appears to be presupposed of misuse of time and resources used to overcome this) that is: re-victimization . It is not considered impertinent, therefore, to conclude that the only thing that brings with it is serious damage to the parties involved. Although it is precisely a magnificent component of the state of the matter.

REFERENCES

AUTHOR

Encarnación Aparicio Martín: Social and teacher pedagogue, specializes in Detection and Intervention in Gender Violence and Equal Opportunities. PhD student and collaborating professor at the Complutense University of Madrid, has extensive experience in Social Intervention, especially in the care of the adult population. He focuses his research in the field of Critical Social Pedagogy.

e.aparicio@ucm.es

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6155-630X

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=QL182yIAAAAJ&hl=es&oi=ao

ANNEXED:

Documento de estudio:

http://www.violenciagenero.igualdad.mpr.gob.es/profesionalesInvestigacion/asistenciaSocial/protocolos/pdf/Punto5PropuestaPAI.pdf