Source: Personal elaboration based on the Zenith Media data report in 2017.

doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2020.51.43-62

RESEARCH

MEANS OF COMMUNICATION AND INTERNATIONAL CULTURAL FLOWS: THE CURRENT VALIDITY OF THE McBRIDE REPORT

MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN Y FLUJOS CULTURALES INTERNACIONALES: LA VIGENCIA ACTUAL DEL INFORME MCBRIDE

MEDIOS DE COMUNICAÇÃO E FLUXOS CULTURAIS INTERNACIONAIS: A VIGÊNCIA ATUAL DO INFORME MCBRIDE

Enrique Vaquerizo-Domíngue1. Doctor in Audiovisual Communication from the Complutense University of Madrid and Bachelor of Journalism and History from the University of Seville.

1Complutense University of Madrid. Spain

ABSTRACT

This article analyzes the relationship between international cultural and communicative flows, taking as a reference the recommendations of the McBride report published in 1980 as a warning to the concentration of media power in the hands of a small number of countries, a situation that favored uniformity cultural on the planet. These pages aim to update that photograph made by said report from the dissection of the origin and control of the media landscape, as well as its main channels and audiences. Through a qualitative research of the main media conglomerates and the most widely spread international television channels in the world, it is established how the mechanisms of cultural influence on the planet work today. The results of the research do not differ substantially from those of the Mc Bride report and show how the control of the media of the main communication conglomerates continues in the hands of a small group of Western countries and that their messages continue to contribute to the dissemination of economic, political models and hegemonic cultural Despite the prevalence of this dynamic, this article also echoes several responses at the local level, from the creation of communication media based on cultural ties and directed in many cases, to migrant communities in the diaspora, to the appearance of innovative opportunities linked to the development of the digital communication ecosystem.

KEY WORDS: networked society, mass media, information flows, cultural flows, cultural identity, intercultural communication, McBride report

RESUMEN

Este artículo realiza un análisis de la relación entre los flujos internacionales culturales y comunicativos tomando como referencia las recomendaciones del informe McBride publicado en 1980 como voz de alerta ante la concentración del poder mediático en manos de un reducido número de países, situación que favorecía la uniformización cultural en el planeta. Su objetivo es la actualización de esa fotografía realizada por dicho informe a partir de la disección del origen y control del panorama mediático, así como de sus canales y audiencias principales. A través de un análisis cualitativo de los principales conglomerados mediáticos y canales televisivos internacionales de más difusión, se establece cómo funcionan en la actualidad los mecanismos de influencia cultural en el planeta. Los resultados de la investigación no difieren sustancialmente de los del informe McBride y evidencian cómo el control de los medios de los principales conglomerados de comunicación continúa en manos de un reducido grupo de países occidentales y que sus mensajes continúan contribuyendo a difundir modelos económicos, políticos y culturales hegemónicos. Pese a la prevalencia de esta dinámica el presente artículo también se hace eco de varias respuestas ensayadas a nivel local, desde la creación de medios de comunicación articulados en función de vínculos culturales y dirigidos en muchos casos, a comunidades migrantes en la diáspora, a la aparición de oportunidades innovadoras ligadas al desarrollo del ecosistema digital de comunicación.

PALABRAS CLAVE: sociedad en red, medios de comunicación, flujos informativos, flujos culturales, identidad cultural, comunicación intercultural, informe McBride

RESUME

Este artigo realiza uma analises da relação entre os fluxos internacionais culturais e comunicativos tomando como referência as recomendações do informe McBride publicado em 1980 como alerta diante da concentração do poder mediático em mãos de um reduzido número de países, situação que favorecia a uniformização cultural no planeta. Seu objetivo é a atualização dessa fotografia realizada por tal informe a partir da dissecção da origem e controle do panorama mediático, assim como de seus canais e audiências principais. Através de uma análise quantitativa dos principais conglomerados mediáticos e canais televisivos internacionais de maior difusão, se estabelece como funcionam na atualidade os mecanismos de influência cultural no planeta. Os resultados da investigação não diferem substancialmente dos informes de McBride e evidenciam como o controle dos meios dos principais conglomerados de comunicação contínua em mãos de um reduzido grupo de países ocidentais e que suas mensagens continuam contribuindo a difundir modelos econômicos, políticos e culturais hegemônicos. Apesar da prevalência desta dinâmica o presente artigo também dá voz a várias respostas ensaiadas a nível local, desde a criação de meios de comunicação articulados em função de vínculos culturais e dirigidos em muitos casos, a comunidades migrantes na diáspora, a aparição de oportunidades inovadoras ligadas ao desenvolvimento do ecossistema digital de comunicação.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: sociedade em rede, meios de comunicação, fluxos informativos, fluxos culturais, identidade cultural, comunicação intercultural, informe McBride

Correspondencia:

Enrique Vaquerizo Domínguez: Complutense University of Madrid. Spain

enrvaque@ucm.com

Received: 26/04/2019

Accepted: 24/06/2019

Published: 15/03/2020

How to cite the article:

Vaquerizo Domínguez, E. (2020). Means of communication and international cultural forms: the current validity of the McBride report. [Medios de comunicación y flujos culturales internacionales: la vigencia actual del informe McBride]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 51, 43-62.

doi: http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2020.51.43-62

Recovered from http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/589

1. INTRODUCTION

The existence of the concept of culture not only implies that of communication, but as Giménez (2009, p. 2) points out, its own expression already implies a process of communication by itself. If we take the symbolic definition of culture as “norms of meanings”, it is observed that the term “meaning” refers automatically to communication. Meanings constitute a product of the relationship between sender and receiver and are generated for the interpretation and decoding of a consignee or group of consignees. Thus cultural products, just like the communicative ones, are always destined and invariably, to an audience that is responsible for reinterpreting them.

Communicative interactions always take place within a cultural framework shared, to a greater or lesser extent, by the actors participating in that process. This cultural framework provides common symbols and codes, reference tables, as well as budgets and respect protocols that facilitate communication.

This way it seems reasonable to affirm that communication is always carried out based on the socio-cultural belongings shared between sender and receiver. When cultural dissonances appear between both actors, the process fails. Communication involves a transaction or negotiation of identities. It is necessary that there is information on the identity of the interlocutor to carry out a process of adaptation to their communication codes at the same time that they modulate themselves. Communication operates on identity and culture not only in its particular dimension, but also in the collective one. In order for a collective identity to come to terms, it has had in the first place to exist a communicative development among its members. These ones have been recreating, selecting and decanting rituals, demonstrations and cultural products; as well as the construction of a collective memory to be transmitted from generation to generation.

Although it is simply accepted the proposition that communication and culture are parts constituting a close relationship, for a long time, the media and its contents were treated in their origin as alien to the concept of culture as well as distorting and “pollutants” elements and of cultural identities. The emergence of mass media was linked initially to the rejection that it inspired between cultural elites and advocates particularistic traditions linked to folklore. These assumptions were mainly related to the studies of the school of Frankfurt, Adorno and Horkheimer (1969), who established a differential line between traditional and industrialized culture, inserted the latter, in the capitalist mode of production generated by the media mass communication

Subsequently, thanks to new perspectives such as Cultural Studies, the fit of the mass media and its mechanisms of production within the cultural tradition were naturalized. With the end of the 20th century, that debate would be shifted to another focus: cultural globalization. A process generated in a context of economic globalization and encouraged by the promotion of communication and information technologies (hereinafter ICT) experienced in the 21st century.

Today the cultural flow that occurs with the transmission of beliefs, habits and values, has accelerated significantly thanks to the technological advancement of the media and the subsequent explosion in a varied of formats and channels. On the other hand they have multiplied the possibilities of access to these ones by more and more countries, which previously were relegated to a marginal role within the international informative circuit. However there are different views about what messages and intentions lie behind these channels and their content, and how they affect complex phenomena such as the cultural international relations, global identities or migratory phenomena.

These visions vary from that aligned with the recommendations of McBride report that considers the media after the arrival of globalization as mediators of culture, responsible for its mass broadcasting and means, after all, at the service of political power and cultural homogenization. Castells (1998) Eiste inou (2004), Montáñez (2005), Segovia (2005), Martín Barbero (2008), Thompson (2008), Travesedo (2014), García Canclini (2017). On the contrary, the trend represented by Honpenhayn (2004), Lévy (2007), Jenkins (2008), among others, who relies on the role of the media, mainly after the extension of their digital formats, as a tool to preserve and disseminate minority cultures thanks to its reticular structures and interactive possibilities.

This technophile vision promulgates overcoming rigid traditional schemes of cultural and communication flows thanks to the emergence of the Network Society. Finally, it is necessary to point out the existence of a more skeptical line about the possibilities of new digital media and cultural flows. In it are the investigations of Dijk (2006) Thussu (2007) Sandoval (2007), its skepticism associated with the digital access gap that still remains among its users.

The present article aims at questioning itself about the relationship of these flows of communication with these cultures and identities that coexist on the planet, mainly through the analysis of the main actors who control the major media conglomerates, paying special attention to their origin. In the globalizing context, the globalization of cultural processes clashes today, in many cases, with the reaction of certain localisms or regionalisms in a symbolic struggle for the conservation of identities. These tensions sometimes escape to the North-South rigid schemes to be represented in the scene of the Western countries themselves, mainly in their most cosmopolitan capitals.

On the one hand, the increase of migratory flows has increased significantly the mobility of citizens and their integration in multicultural societies, this fact has joined the ICT development in a process that favors the non-territorial nature of cultures that find new Digital media to express themselves. Despite these change processes and an increasingly fragmented and changing ecosystem, the Mass Media, whether in analog or digital versions, still play a fundamental role as mediators in the processes of identity negotiation made by their audiences

2. OBJECTIVES

Through the contributions of the literature referred to the subject of media and culture and of the careful analysis of two relevant indicators such as nature, origin and size of the major international media conglomerates, and the most broadcasted TV channels on the planet, this article pursues a main objective: to define the origin and destination of the media messages in the international scene, stopping at the loading of symbolic and cultural contents that they transport.

From this principal objective, I will develop two secondary objectives :

– To elucidate if, based on these flows, the recommendations of McBride report are still relevant.

– To explore various possibilities that have those countries that still have a secondary role in the news circuits to make an impact on their audiences.

3. METHODOLOGY

The bibliographic review has been complemented with the analytical method when establishing a classification on the main international media conglomerates. This classification has been based on the latest data available from the Zenith Media study, data updated and complemented by a thorough study of the Internet sites of each corporation. Its analysis provides an accurate photography of the ownership and origin of the main communicative broadcasting agency. Photography that reveals the direction of cultural flows on the planet. In the same way there has been a qualitative and analytical research on some of the main global cable TV channels. These means have been selected due to the fact they are considered representative regarding the issuance of cultural flows due to both the massive volume of their audiences and their long tradition of transmitters of communicative and cultural flows with North-South direction. A situation on which McBride has already alerted and that still remains present, although updated to the digital context. This research has focused on presenting various aspects of these media such as origin, structure, themes, dissemination and scope of their audiences. For the collection of this data, both online articles and information provided by the television channels themselves have been incorporated.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Communication, culture and power

The perspective of intercultural communication studies, at the end of the 20th century, becomes inter-ethnic, coinciding with the debate on the New Order of Communication. During the past decades, numerous voices of researchers from the countries of the South have risen against the Western “ethnocentric view”, which did not take into account the cultural, social and economic differences of the developing countries that always from this perspective, suffered an “informative colonization” (Zorogastua, 2015, p. 7).

According to Hall and du Gay (2003), the concept of identity is not unique, but would be built in community through a multiplicity of social practices. This author defines two fundamental elements in the process of identity formation: on the one hand the influence of discourse as an agglutinating element and on the other hand the concept of otherness. Identities are constructed from difference in relation, but also in opposition, to others. In this opposition and recognition of otherness, the relations of inequality and power intervene with a very important role.

Group identity values are articulated around belonging to a community and the discourse that supports it. A story about the foundation or the origins, uses and rituals and a whole plot of cultural symbols that the media reinforce order and provide with sense to. The media, far from being devoid of a cultural dimension, contribute to the maintenance of a particular social and political order through the broadcasting of a series of kind of intentional messages.

On the other hand, these communication channels usually reflect the dominant cultural and ideological model of the society to which they belong despite their apparent informative “plurality” (Hall, 1994). Since the appearance of the mass media, and throughout almost all of their history, their ownership, and consequently the issuance of messages with their inherent load of symbols, habits and models, have been in the hands of the cultural and geographical space that is called “western civilization”.

Since the emergence of the cultural industry and the mass media, both communicative and cultural flows, circulated for decades, horizontally between the first western and capitalist world towards the second communist world, an axis that would move with the Time to a new direction: North-South. This last space, corresponding to the so-called “third world”, formed by developing countries located mostly in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The news about the peripheral territories were controlled by the metropolis for years and selected through the filter of correspondents’ offices and news agencies, mostly held by North America and some European countries.

This situation has been perpetuated until the end of the twentieth century, reinforced by the growing development of the mass media, which, like all cultural dissemination institutions, are subject to a whole series of determinations, the most defining of them, their linkage with the ideology of the dominant elite. Hall (1972, p. 1) refers to this phenomenon when he points out that “in England, broadcasting institutions have great formal autonomy from the State and the government; but the ultimate authority to program the means derives from the State and, ultimately, it is the State whose responsibility they are”.

This trend would intensify from the 1990s with the boom in the distribution of global satellite channels, mainly belonging to European countries, which managed to reach instantaneously homes around the world. BBC World, RAI, International, TVE International... all emerged as channels aligned with the geostrategic objectives of the countries to which they belonged with the objective of spreading their culture and influencing the public opinion of third countries in which they broadcasted Tulloch (2009). At the same time, this scenario allowed impact processes and identification of audiences based on affinity variables such as language and culture over geographic boundaries.

These patterns, in terms of the direction of cultural flows, seem to have changed now substantially. Although it is undeniable that the globalized world is increasingly interdependent and that advances in communication technologies play a fundamental role in that scheme. As Travesedo (2014, p. 545) points out, “the global media structure has resulted in the emergence of large corporations influenced by national policies, focused on expanding their ideas, messages, lifestyles and ideologies”.

The economic and political weight continues to be resolved in the ability of different nations and geopolitical blocs to transmit their ideas, and the new media are an effective tool to achieve this. The structure of the information system at the international level is inextricably related to the areas of power and influence in the political sphere.

4.2. McBride report, the first alarm voices

The first voices of alarm regarding the inequality of information flows are unequivocally associated with the McBride Report (1980). This document represented an ambitious project to study the effects at international level that caused the concentration of the media and control of information flows. According to its thesis, the right to the free circulation of information would make the media, instruments at the service of the cultural domination of the group of states that controlled the emission of information flows and propagated them to the rest of the planet.

The McBride report warned about how information from developed countries flows to the less developed ones, with no possibility of return. Its warnings were summed up in the idea that the concentration of media power, in the hands of a small number of countries, ended up exercising in turn an ideological power with influence on the flows of ideas and opinions that ended up modifying the cultures of the developing countries favoring a cultural uniformity in the entire world. Faced with such an imbalance, recommendations were proposed in favor of a democratization of communication, at the global and national level, based mainly on a decentralization of the media and on the protection of minority cultures encouraging their own media development.

During these almost forty years, since the McBride report, the mass media have taken the opposite path to their recommendations; an increasingly evident concentration, integrated into the capitalist market logic where size favors competitiveness. Segovia (2005), argues that the search for constant growth would have led the media to a series of strategies such as market monopolization, search for new niches, brand image enhancement, product diversification and control each time of a greater number of steps in the production chain.

Given the increasing integration of media in the capitalist logic ¿To what extent communication channels transmitted today languages, values and ways of life of minority cultures? Or, on the contrary, do they continue to act as instruments in the service of cultural homogenization from Western countries as McBride pointed out more than 40 years ago? The answer, especially after the generalization of the use of the Internet and the processes of media convergence in the network presents more and more nuances.

Today in the relationship between culture and communication we live in a time marked by the hybridization between the local and the global, but also a technological and media hybridization, in which the cultural information contents are developed and consumed wrapped in transmedia dynamics and from devices increasingly sophisticated . There is an optimistic trend, advocated by authors such as Honpenhayn (2004), Lévy (2007), Jenkins (2008) that highlights the effects that globalization and the arrival of ICT have generated on the ability of recipients to influence in the communicative process, the digital environment would have favored the blurring of the boundaries between senders and receivers causing a decentralization with respect to hierarchies, spaces and supports that established the mass communication and that determined the relationship between sender and receiver.

4.3. Cultural and media flows today

Although the international community is increasingly interconnected, thanks in part to the proliferation and diversity of access to new media, in full Information Society, issuance of communication flows and thus cultural remains tied to the technological capacity and to the geopolitical interests of the countries. Following the theory of the flows of Castells (1999, p. 114), “the generation of wealth, the exercise of power and the creation of cultural codes have become dependent on the technological capacity of societies and people, being technology of information the core of this capacity”. This way, are we still in a scenario, in which the main media conglomerates and communicative flows belong to the countries of the North? Are the recommendations of the McBride report valid to achieve a more egalitarian model from an informational and cultural point of view?

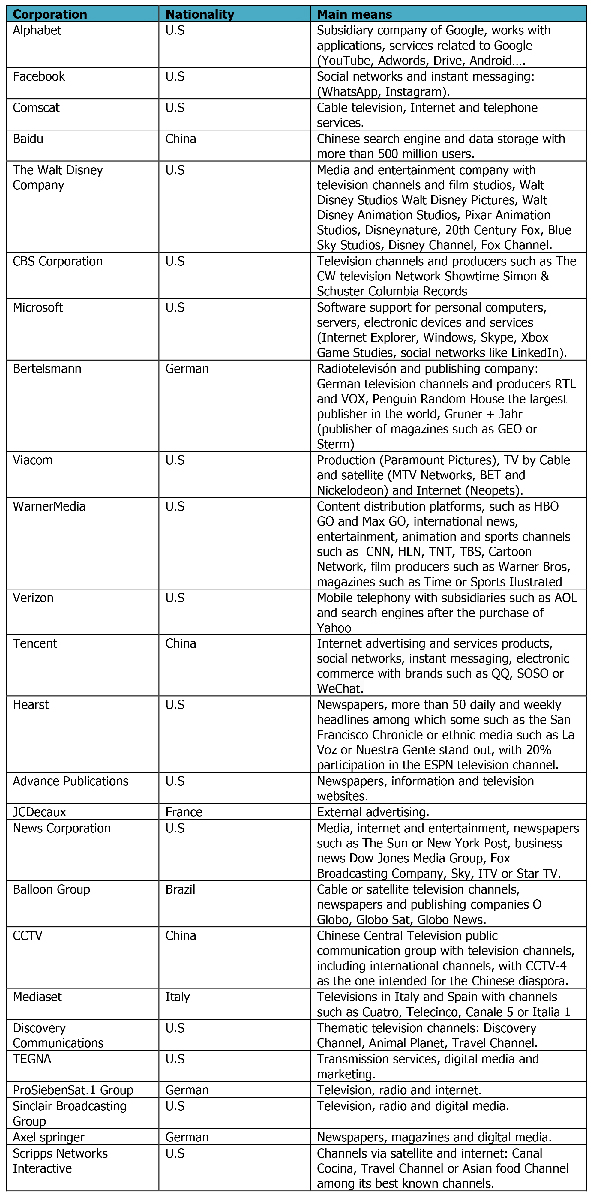

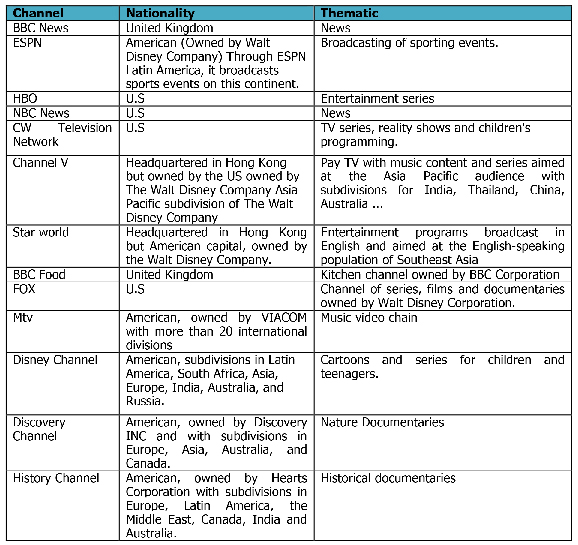

Table 1. 25 main media conglomerates in the world.

Source: Personal elaboration based on the Zenith Media data report in 2017.

Despite these timid changes in the audiovisual landscape, experienced in recent years, if we look at the latest available data, a study by Zenith Optimedia (2017), 18 of the 25 major communication conglomerates worldwide are based in the United States and the highest percentage of its capital is American. Google, Facebook, Walt Disney Company, CBS Corporation, Comcast, Alphabet would belong to what we could call Anglo-Saxon culture. Next to them, among the 25 main corporations, there would be three from China, three from Germany, one from France and one from Italy. From Latin America, the only one that appears in the main positions would be Brazil’s Globo, SA, located in position number 17.

Most of these conglomerates have naturally accepted the arrival and generalization of the use of the network, the insertion into the digital ecosystem and the distribution of transmedia content. The technological “convergence” advocated by Honpenh (2004) has caused business mega-mergers that have integrated the new opportunities. Thus if the arrival of mass Communication blurred the boundaries between high and low culture, today conventional audiovisual media and the new interactive media are found immersed in a new process of concentration.

Thus, in this classification, corporations specialized in audiovisual media, with production companies, written press and editorials coexist with those that work with web browsers, applications, social networks or instant messaging services. However, the passage of Mass Communication to society to network does not seem to have changed the origin and ownership of channels, issuers and messages; these seem to be concentrated except for exceptions in the same countries as forty years ago when the McBride report stated the first alarm signals.

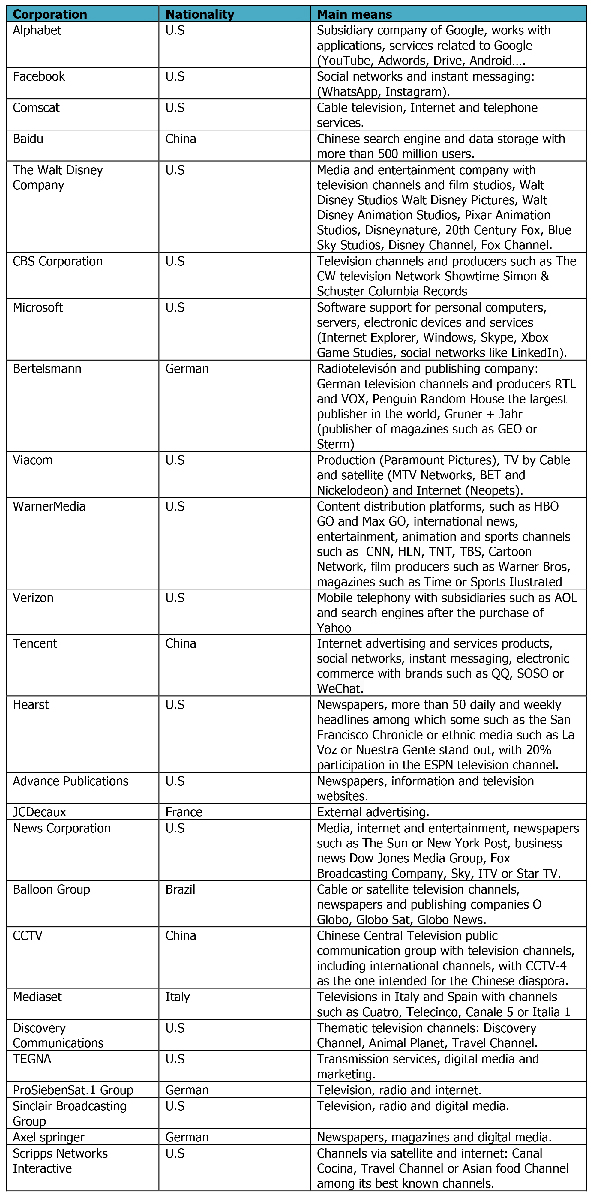

Table 2. TV Channels with most diffusion on the planet.

Source: own elaboration based on information from Marketing91 and Trendrr.net.

In analyzing a diffuser par excellence of cultural flows such as satellite TV and making reference to some of the most watched channels in homes around the world: BBC, HBO, MTV, Disney Channel or ESPN, it is observed how in practice all also belong to British or American conglomerates . Most of them have subdivisions for Latin America, Asia and even Africa in which the contents are adapted to the language and, sometimes, supposed interests of their audiences. Outside the Western ground only stand out Star TV and Channel V, Channels based in Hong Kong and directed exclusively to the public of Southeast Asia but they also belong to Western conglomerates.

This way, some reference television channels related to some of the most relevant aspects for the formation of a culture such as information, language and history and even gastronomy, children’s education, music and sports, they are controlled by Anglo-Saxon Capital today, which would decide the guidelines and content programming that is consumed in the homes around the world.

In the US case, following Segovia (2004), its media conglomerates, in most cases they are participated by other sectors such as banking or oil and they are supported by public policies that support their development. These policies have traditionally privileged information as an actor of enormous influence in international geopolitics, in which cultural domination joins others such as military or economic.

4.4. The network society: a new paradigm of media and cultural flows?

Although some of the conclusions of the McBride report have become obsolete and are not enough to fully explain the informative reality of the 21st century, it is true that information flows continue to come mainly from developed countries. However, the access to sources of information with the network development and generation of new own channels has also been expanded, implemented by countries that previously belonged to secondary informative circuits. Through the technological revolution of the past decades and the proliferation of media, a large majority of communities that previously lived isolated, are now interconnected. In this process, along with the Internet, television has not lost relevance, as a modifier of social aspirations and economic as well as cultural models of behavior of societies where they had remained unchanged for centuries.

From this point of view, the domination of cultural identity remains linked to economic and political interests and is reproduced, as Castells (1996, p. 211) points out, through the global and abstract flows of wealth, power and information, which build real virtuality through media networks. The opening of the poles of political and economic influence towards emerging nations entails the emergence of global media with headquarters in countries that had traditionally had the role of mere receivers, changes that have been translated mainly in the audiovisual landscape. During the last two decades, there have been the first South-South information flows and a significant blurring of the concepts of center and periphery.

Some countries traditionally considered peripheral in the information circuits years ago began to consolidate as exporters of cultural products, mainly audiovisual, aimed at population niches with which they share identity affinity. Highlights include the cases of Al Jazeera, Telesur, CCTV or Univisión, channels that target broad audiences with which they share language, origin or cultural identity.

Among these niches are minorities of migrants residing in increasingly multicultural societies. These television channels operate in many cases as support to connect the diaspora of a community dispersed throughout the world or just displaced from their hometowns to other sites more or less close by. In some cases, this use is motivated by the interest of different governments in keeping alive the relationship between emigrants and their country, among others, for reasons of economic type such as the CCTV Chinese public channel and the Chinese diaspora in the world (Amezaga, 2004, p. 8).

At present, groups of diaspora have, for the first time, the possibility of accessing media from their home communities that allow them to consume content in their own language, attend a religious ceremony or follow the same series that they saw in their country of origin without leaving home. For them, new television channels have also been created, broadcasting from the host society itself. So they have spread cases like Hispan TV or International Cordoba, Muslim television channels broadcasting to the Muslim community in Spanish - speaking countries, that also try to spread propaganda among their audience on the Iranian regime and the Saudi monarchy respectively.

With the opening of the television panorama, through the occasional inclusion of audiovisual channels dedicated to minorities within large international conglomerates, there are also certain audiovisual and cultural counter-flows from the South to the North, although these flows are still minorities. Soap operas, as Thussu (2007, p. 48) points out, are an example in that regard; produced in Mexico, Colombia, Brazil and Venezuela, they are broadcasted through their respective corporations by channels dedicated to ethnic and cultural minorities, but which are openly broadcasted throughout the US territory, as it is the case of Latino TV.

Despite this change in trend in audiovisual flows, critical authors such as Gómez (2016) point out that these contents help to reflect cultural stereotypes and are not broadcasted in the main national channels in the United States, but in secondary cultural markets based on a diaspora and ethnic component, and destined in many cases to commercial penetration in the niche they represent. In the same way, this diversification of the large media conglomerates towards regional divisions, or the adaptation of their contents to reach ethnic minorities, is due more to an exploration of new standardized audiences than to a real direction towards the democratization of cultural flows.

The arrival of ICT does seem like a possibility to alter the unidirectional cultural flow of mass communication about which the McBride report warned. These tools and as García Canclini (2017, p. 19) states, have become mediators of communication and culture and an opportunity for all communities seeking to find their socio - cultural recognition. However, despite the changes that are beginning to be outlined, there are still doubts about whether cyberspace would continue to contribute to consolidate the cultural hegemony of the nations that control traditional media conglomerates, or if it also allows the presence of other non-Western cultures .

The arrival of the digital ecosystem brought with it the term Lévy cyberculture (2007, p. 12), conceived under technological, media and cultural hybridization. A digital Space and open for production and consumption through collaborative and horizontal networks formed by users who managed to break rigid borders between transmitter and receiver marked by traditional mass media. Currently, individuals may be associated in virtual communities and social networks based on their interests and cultural affinity and contribute democratically content breaking apparently the monopoly of the media on their production. However, the media continue to have a great weight in the generation of these contents that represent a necessary fuel for the interaction of these spaces.

Altogether, despite the new communicative trends sketched in this chapter and the possibilities offered by ICT, emphasized by technophiles such as Honpenhayn (2004) or Lévy (2007), the directionality and concentration of the media level worldwide, with the consequent cultural standardization in the issuance of messages are still valid and linked to the centers that produce wealth (Travesedo, 2014, p.9). Despite the considerable effects of the digital revolution, there are still large segments of the population that have the role of mere recipients of cultural flows or that sometimes cannot even access them.

In access to information through ICT, despite the tendency to raise virtual interactions to an exclusively “metaphysical” level and minimize the importance of devices, physical and virtual elements coexist permanently; As Sandoval (2007, p. 14) points out, not everything that happens in cyberspace is separated from everyday reality.

In order to produce interactions in a virtual community, a technological substrate such as a screen, a telephone, a connection is necessary... Access to them is determined by the economic conditions of individuals, social position, employment, status, group or membership groups, language, Culture and religions. These variables end up conditioning, fundamentally, the virtual sociability of individuals. The democratic and horizontal nature of ICT does not automatically reproduce a condition of equality of individuals in the Information Society.

If inequality in the direction of communication flows has persisted to this day, there are also inequalities in access to ICT that, despite a clear decline in recent decades, still have nuances that influence the position that a community occupies in the Society of Information. The concept of the digital gap, which we could define from its classical perspective as “the distance between those people who have and do not have access to the Internet” (Dijk, 2006, p. 221), serves to illustrate this phenomenon. The digital gap represents the dissimilar social impact caused by ICT, as well as the distances established in terms of the development opportunities of the populations that use them.

The use of technology can mark a border between “rich” and “poor”, with access to information as a differentiating capital. In this context, only the privileged are able to reap the social and economic benefits of access to the global information and communication infrastructure. This new form of exclusion is reproduced through two aspects: the international digital gap (the gulf that separates regions and countries) and the domestic digital gap (it divides the groups of citizens of a society) (ECLAC, 2003). The digital gap separates those that are connected to the digital society through ICT from those without access to the benefits of the new technologies and produces, as noted Tello (2007, p. 3), through the international borders, but also within the local Communities divided by economic barriers and access to knowledge.

Over the past few years, internet penetration rates have reached very high rates, causing a significant decline in the digital gap, although some differences persist. According to data from Nielsen consulting firm (2017), internet penetration rates for North America and Europe would be 88% and 77%, respectively, if compared to 59% in Latin America and 28% in Africa. The latter has grown at a rate of more than 1,000% in recent years, so it is presumable that this difference despite being still significant is remedied in a short time.

Now, the most recent studies on the digital gap are not limited to assessing access to the services offered by the internet, but also taking into account the quality of such access and the availability of broadband connections that allow access to multimedia content in times and costs appropriate to the context of the users. Dijk (2013), after studying the behavior regarding the use of digital technologies in the network of hundreds of Dutch people, concludes that variables such as age, ethnicity or education, influence variables such as age, ethnicity or education, and that extracting the maximum performance of these ones, has a favorable impact on the establishment of extensive and rich networks in the offline environment.

From this point of view, the architecture of the digital gap would be established through two directions: a horizontal one in which poverty would generate digital exclusion and a vertical one based on policies that, through infrastructure development, would guarantee, or not, equal access to all its citizens.

5. CONCLUSIONS

After analyzing the origin of the main communicative conglomerates of the international scene, it is evident that most of them belong to corporations with capital from Western countries, mainly Anglo-Saxons. Research on the main satellite channels on the planet offers similar results; the majority belong to British and American conglomerates. Although some of them have continental subdivisions and adapt content to their audiences and languages, their program scheduling is usually decided at headquarters, spreading hegemonic, cultural, and informative flows regarding the capital from which they come. Many of these spaces are thematic channels focused on key aspects for the creation of a culture, which would be the language, history, gastronomy, education children’s, music and sports . Their programs spread a corresponding load of Western symbolic contents that are consumed by audiences around the world, in many cases belonging to countries that continue to occupy a marginal place within the game of the distribution of informational and cultural flows.

In relation to the second objective proposed in this research, to verify the validity of some of the recommendations of the MCBride report, it is necessary to point out that it warned about the fact that the communication industry was dominated by a relatively small number of companies that concentrated almost the whole process of production and distribution, of transnational vocation and located in the main developed countries. Its main recommendations influenced the need to liquidate internal and external barriers, which prevented the free movement of information, as well as to guarantee freedom of the press, the plurality of sources and channels of information, rather than the emergence of the Digital information system and the development of ICT, multiplying the information offer seem to have limited at least in appearance.

The arrival of the internet and the economic development of some of the countries traditionally located in the informative periphery, also seems to have helped to advance in other of the main lines of recommendations of the report: To respect the cultural identity and the right of each country to inform the citizens of the world about their aspirations, social and cultural values, or to respect the right of all the peoples of the world to participate in international information flows and of the citizens to access information sources and to actively participate in the communication process. At present, in the international audiovisual field, when talking about information flows and their cultural influence, different situations coexist: from the predominance of Northern countries as transmitters of persuasive messages that continue to spread, as the Mc Bride report warned for decades, the hegemonic Western culture, to the development of new audiovisual trends focused on very specific cultural communities, which for the first time have the opportunity to consume content, especially directed towards them. In both situations, there is an intentionality in the issuance of messages with a clear geostrategic will.

Despite the timid advances, the results of this research show that there has been no substantial progress in one of the main recommendations, reducing the scope of information monopolies and their effects. In the 21st century, the control and issuance of the majority of informative messages with their corresponding symbolic load and cultural flows continue in the hands of a few countries, favoring a worldwide cultural standardization as the report warned. In these forty years, the mass media have embarked on an increasingly evident process of concentration. In spite of the diversification of formats and contents and the apparent empowerment of the recipients thanks to the passage of a Mass Communication to a networked Society, the channels and information flows continue in the hands of the majority of the western countries and therefore the complaints and recommendations made by the report remain valid. The emergence of ICT has not caused the disappearance of traditional media. On the contrary, in many cases they have been integrated, diversifying their uses and modes of consumption, in the same way some of the most important spaces of the digital environment such as Facebook or Google are also owned by Western capital that has integrated them into a phenomenon of media concentration increasingly horizontal and diverse.

Among the objectives of this research was to explore the various possibilities available to those countries that still occupy a secondary role in the information circuits to reach their audiences. While the research method chosen has not deepened in aspects such as new digital spaces and trends of exclusive consumption of these countries, leaving room for future research, the observation of new phenomena and forms of digital communication allows to conclude some countries traditionally relegated to marginal roles within the information circuits, launch audiovisual channels and digital communities with a vocation of geostrategic influence and diaspora articulation regarding cultural affinity audiences.

In the same way, despite the conditions indicated above, it can be emphasized that ICT have also provided tools for those communities that had traditionally remained relegated in the classic cultural and informative circuits, favoring a certain diversification. However, in practice, a large part of the population of these countries continues to go through difficulties to take advantage of these opportunities, difficulties associated with the digital gap in both access and use. This way, the panorama on the control, and issuance of communicative, and cultural flows, seems open today: if ICT have brought about the convergence of formats and informational contents as well as of the cultural industry, the communication companies mostly belonging to the western countries, have reacted with mega-conglomerates, in which they integrate business lines, both the ones related to the traditional mass media, and those related to the access and use of the network.

REFERENCES

AUTHOR:

Enrique Vaquerizo Domínguez: He has a PhD in Audiovisual Communication from the Complutense University of Madrid and a Degree in Journalism and History from the University of Seville, he is a journalist and consultant in Corporate and Social Communication as well as a professor of the Master’s in Political and Institutional Communication at the University Camilo José Cela. He has published articles in national and international magazines and has participated in various collective books, congresses and conferences related to the themes of migration, communication and ICT.

enrvaque@ucm.com

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4146-9900

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=yy9GQ6wAAAJ

Academia.edu: https://independent.academia.edu/EnriqueVaquerizoDom%C3%ADnguez