doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.49.123-140

RESEARCH

PHOTOGRAPHY, MEMORY AND IDENTITY

FOTOGRAFÍA, MEMORIA E IDENTIDAD

FOTOGRAFIA, MEMÓRIA E IDENTIDADE

José Muñoz Jiménez1

Professor of the Department of Audiovisual Communication and Advertising of the University of Málaga, he is a specialist in documentary photography and audiovisual media. His research in audiovisual communication is related to the field of anthropology and fine arts

1Malaga University. Spain

ABSTRACT

The interest of this work lies in the revision of some of the elements of language inherent to audiovisual creation, through the analysis of a specific case belonging to the photographic medium, and located in the geographical space of the Moroccan city of Fez. The photographic perspective that interests us here is that of the ratification and certification of the referent that reproduces the photograph, based on the description that “every photograph is a certificate of presence” (Barthes, 1990), which together with its essence, places it in what we could metaphorically call, a mirror of reality, apprehending all that it reflects. Its physical essence captures the “trace of light” beyond the mirror that inverts it, in that magical distillation of light in the darkness of the camera, which as a metaphor for the cave, will place us in the perspective of the knowledge of the social sciences. In this way, every photograph tends to transfer physical space to move it into mental space, in clear association with memory. This relevance and photographic effectiveness will seldom have anything to do with the intentionality of the author, since this visual production is within the reach of the community that assumes it, configuring itself as strong elements of the identity, together with the imaginaries that it invokes and the construction of cultural archetypes.

KEY WORDS: documentary photography, identity, social memory frames, imaginary, Fez, orientalism, photographic theory

RESUMEN

El interés de este trabajo radica en la revisión de algunos de los elementos del lenguaje inherentes a la creación audiovisual, mediante el análisis de un caso concreto perteneciente al medio fotográfico y situado en el espacio geográfico de la ciudad marroquí de Fez. La perspectiva fotográfica que aquí nos interesa es la de la propia ratificación y certificación del referente que reproduce la fotografía, atendiendo a la descripción de que “toda fotografía es un certificado de presencia” (Barthes, 1990), que unida a su esencia desde el momento inicial, la emplaza en lo que podríamos denominar metafóricamente, espejo de la realidad, aprehendiendo todo aquello que refleja. Su esencia física capta la “huella de luz” más allá del espejo que la invierte, en esa mágica destilación de la luz en la oscuridad de la cámara fotográfica, que a modo de metáfora de la caverna, nos va a situar en la perspectiva del conocimiento de las ciencias sociales. De esta manera, toda fotografía tiende a traspasar el espacio físico para trasladarlo al espacio mental, en clara asociación a la memoria. Esta pertinencia y efectividad fotográfica pocas veces va a tener que ver con la intencionalidad del autor, toda vez que esta producción visual queda al alcance de la comunidad que la asume, configurándose como elementos fuertes de la identidad, junto a los imaginarios que invoca y la construcción de los arquetipos culturales.

PALABRAS CLAVE: fotografía documental, identidad, marcos sociales de la memoria, imaginario, Fez, orientalismo, teoría fotográfica

RESUME

O interesse deste trabalho radica na revisão de alguns dos elementos da linguagem inerentes à criação audiovisual, mediante a analises de um caso concreto pertencente ao meio fotográfico, e situado no espaço geográfico da cidade marroquina de Fez. A perspectiva fotográfica que aqui nos interessa é a da própria ratificação e certificação do referente que reproduz a fotografia, atendendo a descrição de que “toda fotografia é um certificado de presença” (Barthes, 1990), que unida a sua essência, se situa no que poderíamos denominar metaforicamente, espelho da realidade, aprendendo tudo aquilo que reflexa. Sua essência física capta as “marcas de luz” mas além do espelho que verte, nessa magica destilação da luz na escuridão da câmera fotográfica, que ao modo de metáfora da caverna, nos situa na perspectiva do conhecimentos das ciências sociais. Desta maneira, toda fotografia tende a transpassar o espaço físico para translada-la ao espaço mental, em clara associação à memória. Esta pertinência e efetividade fotográfica poucas vezes terá que ver com a intencionalidade do autor, toda vez que esta produção visual fica ao alcance da comunidade que à assume, configurando-se como elementos fortes da identidade, junto aos imaginários que invoca e a construção dos arquétipos culturais.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: fotografia documental, identidade, marcos sociais da memória, imaginário, Fez, orientalismo, teoria fotográfica

Correspondence: José Muñoz Jiménez. Malaga University. Spain.

josemunoz@uma.es

Received: 6/03/2019

Accepted: 10/04/2019

Published: 15/07/2019

How to cite the article: Muñoz Jiménez, J. (2019). Photography, memory and identity. [Fotografía, memoria e identidad]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 49, 123-140. doi: http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.49.123-140

Recuperado de http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/581

1. INTRODUCTION

We must clarify that the photographic image that interests us here is that which is reproduced from the natural image, and in any case the images that, while maintaining a high degree of iconicity, could have been manipulated. Therefore we will not refer in this article to the photographic image synthesis, which can be created without direct physical reference, nor Include in this research images on photographic support that exclude the direct molding of the light on the registered referent.

We understand that photography is an image registered with a “high degree of iconicity” (1) (Villafañe and Mínguez, 1996; p. 41), which testifies to the physical referent that it reflects. According to the defining convention, photography is the “procedure or technique that allows us to obtain fixed images of reality through the action of light on a sensitive surface or on a sensor” (DRAE, 2018) (2).

Our interest focuses in turn on images that maintain the photographic “testimony principle” above any other possible interest of the author, in terms of their communicative intention. Dubois affirms on this principle, that “at the same moment that one is before a photograph, it can only refer to the existence of “the object from which it comes (...) [therefore the photography] certifies, ratifies, authenticates. But this does not imply, however, that it means” (Dubois, 1986), or we might add, the author intends to mean. On the contrary, Barthes guides this meaning through the action of history itself, the photographic insignificance according to which its meaning will always be associated with its code of connotation, “the reading of photography is always historical; it depends on the “knowledge” of the reader, just as if it were a true language, which is only intelligible to the one who learns its signs” (Barthes, 1986).

(1) Villafañe and Mínguez place it in seven and eight, according to the black and white or color photography, with number one reserved for no-figurative representation and eleven, maximum, for the natural image.

(2) http://lema.rae.es/drae/?val=fotograf%C3%ADa (update 2018). It is necessary to point out the change and update of this definition from the previous one that the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language collected in the edition of the year 2009 in its dictionary: “art of fixing and reproducing by means of chemical reactions, on suitably prepared surfaces, the images collected in the background of a darkroom”.

2. OBJECTIVES

The main objective of this work is to demonstrate how the cultural context of an era models the cultural forms of that historical time, creating those elements that contextualize the language of photographic creation. Specifically, we think that photographs taken by photographers whose motivations, whether economic or personal, were influenced by the Orientalist representation of their images by other photographers who previously worked on different themes in the city of Fez.

For this we have to answer two questions: what mechanisms relate photography and memory? and What relates photographic memory and identity?. The answers are going to serve us to verify the imagination of Fez.

At the same time, we wanted to show how, together with the fact of evolution in the photographic representation of Fez, there has been an Orientalization of architecture in terms of its forms.

3. METHODOLOGY

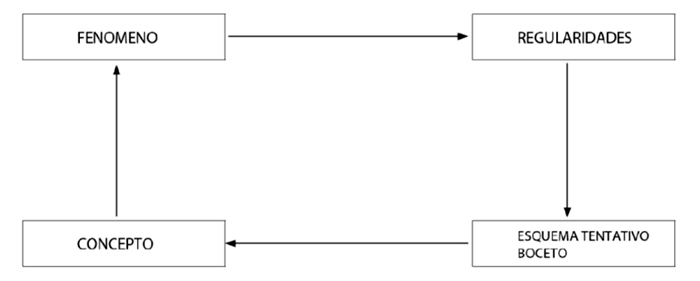

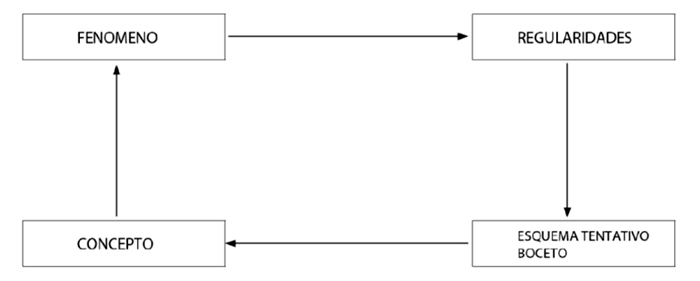

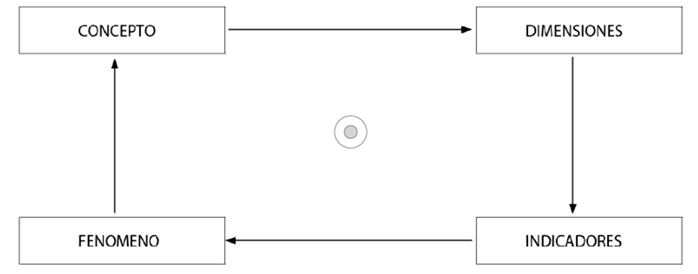

We have taken as a reference at the beginning of this research work the theoretical framework referred by Pedro González Blasco (Figure 1) in his article on “the way to measure in an empirical investigation” in which develops the first level of research of social facts. González Blasco describes the sequence that guides the research, framed in the context of the social sciences and using a qualitative methodology. We also agree with González Blasco that this type of methodology justifies better study topics as broad as ours, of which we will only develop part of the research here. In the following table (Figure 2), we show the sequence proposed by González Blasco and initially followed in the evolution of the research process.

Source: González Blasco (1993, p. 232).

Figure 1. First level research of social facts.

Both the historical context of the theme developed, as the context of realization of the photographs are important to understand the mechanism of the elaboration of these photographic images, oriented in their time of realization to different publications and photographic archives, or made simply by hobby of the photographers who were there.

Source: González Blasco (1993, p. 232).

Figure 2. Cycle and decomposition of the elements of the concept.

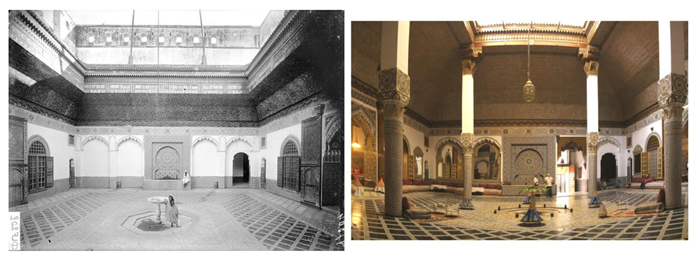

Regarding the goal of the Orientalization of architecture in the Medina of Fez, we intend to use the methodology of rephotography, which, based on the anthropological methodology of comparative analysis, starts from an image made in the past and that serves to establish, starting from the contrast with the present, the changes that have occurred in the object studied. His interest is produced at different levels and serves to specify any type of analysis on the passage of time in the object of study.

4. DISCUSSION

We intend to relate photography with the concepts of memory and identity, as these are systems that articulate and enrich each other. For this it is necessary to begin by understanding the imaginary in front of the world of images.

In the words of Gilbert Durand, the imaginary is like “the museum of all the past, possible, produced or to be produced images” (Durand, 2000). But what are the images? For Vilém Flusser the image is “a surface with meaning, whose elements interact magically” (Flusser, 2001) that have to be read, while Sartre establishes a classification of the image based on his phenomenology:

The image is an act that seeks to achieve in its corporeality an absent or non-existent object, through a physical or psychic content that is not given properly, but as an «analogical representative» of the object considered. [For this] we will distinguish, then, the images whose matter is taken from the world of things (photography) and those that take their matter from the mental world (Sartre, 1964).

One of the aspects of the images that presents a greater interest for us is that they are associated with symbolic issues and visual language. “The nature and understanding of figurative images, of what is sometimes called ‘iconic languages’, is rooted in the intersection of biological phenomena (such as perception and memory) and cultural factors (such as the symbolizing capacity of man in different times and places” (Gubern, 2006).

An aspect related to the image is the imagination, the “specific capacity to abstract surfaces of space-time and to reproject them to space-time” (Flusser, 2001; 11), and as this in turn is also related to magic, what connects images and imaginaries. “The act of imagination is a magical act. It is an enchantment destined to make appear the object in which one thinks, the thing that is desired, in such a way that one can enter into its possession” (Sartre, 1967).

Sartre is interested in the imaginary not from the field of theories but from the reflection, following as a method what he calls the formulation of images: to produce images in us, to reflect on them, to describe them, that is, to try to determine and situate its distinctive characteristics. “Every new study dedicated to images has, then, to begin with a radical distinction: one thing is the description of the image and another the inductions that interest its nature” (Sartre, 1964).

We could affirm then, that if the thought does not have another content that the order of the images, the study of these should be incorporated to the study of the mental images:

There is no world of images and a world of objects. But every object, whether presented by external perception, already appears in the intimate sense, is capable of functioning as present reality or as an image, depending on the center of reference chosen. Both worlds, the imaginary and the real, are constituted by the same objects: only the grouping and interpretation of these objects vary. What defines the imaginary world as a real universe is an attitude of the consciousness (Sartre, 1964).

4.1. Photography and memory

Photography freezes in its appearance that time frame that returns us to the moment of «act» and that of nostalgia, necessary for the psychological device of memory to materialize. “The photographic images symbolize as much as the mental ones our perception of the world and our memory of the world” (Belting, 2007). Photography is also this strange game of inversions that acquires other senses beyond mere reproduction, thus extending its duration, which normally exceeds that of a generation. The fact therefore acquires a great importance as a physical support of the collective and individual memory. However, in this function of memory support, photography presents great fragility in terms of the possible manipulation associated with its use, coinciding with memory in that it can be problematic, deceptive and sometimes treacherous (Yerushalmi, 2002). Thus:

The knowledge referring to the printed factual state must be provided in addition (next to the image), if it does not already have it in. Regarding intentionality, unless it is encoded by visual stereotypes or verbally communicated, it can only lead to a hypothetical reconstruction from the context of perception” (Schaeffer, 1990).

Or as a photographer warns: “My suspicion before the mirror is sharpened by even more complex devices such as the camera, of which the mirror has often acted as a metaphor” (Fontcuberta, 2000).

So we can ensure that its reading, obey the interpretive structures of the moment and the culture that structures it, contributing what is visible to the mechanisms of understanding reality, and thus being able to specify its relationship with general knowledge, and our memories: “The image is thought, without establishing any kind of relationship with any intellectual meaning, and the concept is defined by stripping it of any image. If we admit that the image-memories are conserved and reappear, it is because we can reconstruct them with concepts that are so defined” (Halbwachs, 2004).

Barthes spoke about this recurring theme of memory, the use of photography and its status in the inner worlds, of the memory of important aspects such as the memory of his mother in an old photography (Barthes, 1990), a photograph of which he speaks and that nevertheless does not include next to the text, as he does with the other images with which the text deals with, conserving the photograph of his mother for his privacy and of which only the reader participates by means of a small description, thus maintaining in a powerful way our attention on a photograph that we do not see. “Remembering means selecting certain chapters of our experience and forgetting the rest. There is nothing so painful as the exhaustive and indiscriminate memory of each one of the details of our life” (Fontcuberta, 2000).

The images of the postcards are important in this investigation, since they are the supports of the image that best show the colonial look, the social and cultural psyche of the colonizer that we can glimpse, evoking certain «ghosts» of the imaginary associated with the colonized. As it happens, “between the thought of the dream and that of the vigil there is, in effect, that fundamental difference that one and the other do not develop in the same frames” (Halbwachs, 2004), in the same contexts of understanding.

Bergson does not admit incompatibility between memory and dream, “under the name of images-memories, they designate our past itself, preserved in the depths of our memory, and did where the mind, in circumstances that it would not be already oriented towards the present, and that the activity of the vigil had relaxed, should naturally re-descend” (Halbwachs, 2004). However, “it is not in the memory, it is in the dream, that the mind is the furthest from society” (Halbwachs, 2004). For Bergson (1900), the imagination is memory, the image as a memory, but memory reconstructed, as for Halbwash: “Out of the dream, the past, in reality, did not manifest itself as it is and everything seems to indicate that it was not preserved , but it was reconstructed from the present” (Halbwash, 2004).

All the existing production of images, independently of the chosen and/or preserved support, interests us to build our work. Any destruction, cancellation or concealment that keeps these photographic materials in the dark, will condemn our claims to review the past. Without memory we cannot remember what it was, we can only make children’s stories or those pastiche architectures that are currently generated in the style of Disney cities, Las Vegas, and so on. Therefore “there is no possibility of memory outside the frames used by men living in society to fix and recover their memories” (Halbwachs, 2004). “Both our notion of the real and the essence of our individual identity depend on memory. We are not but memory. Photography, then, is a fundamental activity to define us that opens a double access road to self-affirmation and knowledge” (Fontcuberta, 2000).

4.2. Social frames of memory and identity

The concepts of identity and memory are strongly related, to the point that they cannot be easily studied separately. Another concept, such as imagination, shapes the private spheres of our existence and affirms our referents, which will coincide with a given community and/or culture with greater or lesser force. Social frameworks of memory organize the structure of our memories, our social institutions, our forms of communication, our spatial movements, they give sense, in any case, to the own existence, integrated into a particular community.

These collective frames of memory are not simple empty forms where the memories that come from other parts would fit like an adjustment of pieces; On the contrary, these frameworks are-precisely-the instruments that the collective memory uses to reconstruct an image of the past according to each era and in tune with the dominant thoughts of society (Halbwash, 2004).

Based on the analysis of the collective memories of family traditions, religious groups and social classes, Halbwachs states, in reference to the structures of memory, that “the individual remembers when he assumes the point of view of the group and that the memory of the group is manifested and performed in individual memories” (Halbwachs, 2004). Above all, this effort to objectify the collective processes of memory, a series of questions arise that are important to ask:

How to understand that our memories, images or a set of perceptible images can be the result of a combination of schemes or frames? If the collective representations are empty forms, how could we achieve, by bringing them together, the nuanced and sensitive matter of our individual memories? How could the continent produce the content? (Halbwachs, 2004)

In reference to our research it is necessary to understand that otherness also acts as a social framework or, at least, there are clues to take a position on the «other». In the radical exoticism of V. Segalen (1986), the possibility of becoming «another» in that probable change of identity, which is something exceptional, does not allow aesthetic contemplation. On photography and exotic experience raises Baudrillard, “it is just photographic what is violated, surprised, unveiled, revealed in spite of itself, which never should have been represented because it lacks image and self –awareness” (Baudrillard, 1991, p. 163). However, we consider that this affirmation of Baudrillard is that of radical exotica, which falls into its own vicious circle. We believe that “the vision of the «primitive» as a creature that lives by rigid norms, in total harmony with its surroundings and essentially exempt from glimpses of self-recognition, is but a set of complex cultural projections. There are no «primitives» but we meet other men who lead other lives” (Rabinow, 1992, p. 142).

Within primitive societies time is not «real» historical time, but only mythical time, the time of the primal beginnings and the paradigmatic first acts, the dreamed time when the world was new, the unknown suffering and the men lived with the gods. In fact, in such cultures, the present historical moment has very little independent value. Acquire meaning and reality only when it is altered, when, through the repetition of a ritual or the recitation or representation of a myth, historical time is periodically torn apart, and one can experience again, although only briefly, the true time of origins and archetypes. And these vital functions of myth and ritual are not confined to the so-called primitives. Along with the mentality they reflect, the great pagan religions of seniority and others share it also (Yerushalmi, 2002).

However, if we agree with Baudrillard in his statement about the interest of exotic photographic motifs that create the fascination of the «disclosed, revealed, violated», a fact that still continues to reflect some of the photographs and postcards of the colonial era, to which an element with a high degree of significance has been attached as is the passage of time. Imagine the context and the meaning that these photographs and postcards that circulated throughout the metropolis had in their historical moment, which finally formed a great number of meanings and models of reality:

The magical nature of the images must be taken into account when deciphering them. (...) The images are intermediaries between the world and men. Man exists, that is, he does not access the world immediately, but through the images, which allow him to imagine it. But as soon as they are represented, they stand between the world and man. They serve as maps and become screens: instead of representing the world, they disfigure it, until man finally begins to live according to the images he creates. Stop deciphering the images to project them undeciphered to the outside world, with the consequence that the world transforms for him into a kind of image, in a context of scenes or situations. This reversal of the function of the image can be called «idolatry», and now we can observe how it is produced: the omnipresent technical images that surround us are restructuring our «reality» magically, turning it into a global scene of images to orient oneself in the world. When he loses the ability to decipher them, he begins to live according to his own images: the imagination has become hallucinated (Flusser, 2001, p. 12-13).

During the dream it happens that the images follow each other out of reality, of our memories, and yet this is not usually the case:

If the dream were, in reality, the result of an encounter and an assembly between the memory preserved as it is in the memory and a beginning of sensation, it would be necessary that, during the dream, some images appear that we would recognize as memories, and not simply those of which we would understand the meaning. The conditions are most favorable, since these blurred impressions, changing colored spots, confused noises, allow the access of the conscience to all those memories that are ordered in a fairly extensive framework (Halbwachs, 2004, p. 66).

History in its sequential evolution could be justified as one of the possible frames of memory, in the creation of identities, since it has a sufficiently rich structure in all its elements, nuances, and even contradictions, to mark the axis of archetypal knowledge, but by itself does not seem to be enough, because as Durand says, it is closer to the myth.

We can affirm first that history does not explain the archetypal mental content, since history itself is of the domain of the imaginary. And above all in each historical phase, the imagination is completely present, in a double and antagonistic motivation: pedagogy of the imitation, of the imperialism of images and the archetypes tolerated by the social environment, but also adverse fantasies of rebellion due to the rebellion of this or that regime of the image by the historical medium and moment (Durand, 2005. p. 398).

4.3. Photography in Fez

The photographs taken in Fez during the early twentieth century have gone through different historical vicissitudes depending on the motivating fact that originated them or the medium in which they materialized, following developments parallel to historical events in terms of political, social, anthropological, psychological, artistic, etc.

We believe that there would be three major periods in the appearance and development of photography in the interior of Morocco. These periods were marked by the following historical events: The first, we could call it the flirtation of the European powers with Morocco, ranging from the last decades of the second half of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century, specifically the Madrid Convention of 3 July 1880 between France, Germany, Austria, Belgium, Spain, the United States, Portugal, Sweden, Norway and Morocco, regulated the Right of Protection, recognizing among others the property rights of Europeans in Morocco under certain conditions, introducing also some restrictions on the naturalization of Moroccans (Cousin, 1905 ). It is not the first agreement but it is the beginning of the appropriations of the territory that increasingly favored the powers. In the Franco-English agreement of April 8, 1904 explicitly set the distribution agreement between England and France, respectively Egypt for England and Morocco for France (Cousin, 1905 ), this being the end of which we consider this first period, leaving France in clear advantage over Germany thanks to the developed agreement; the second period to consider would be the military occupation and subsequent protectorate of France in Morocco; and the third period would start in the mid-fifties of the twentieth century, coinciding with the new paradigm that was to model Morocco, thanks to the declaration of independence of 1956, and the differentiation in terms of political/social forms of the country, without an occupying army that conditioned social customs with their different customs, as was the French army of the protectorate era.

Despite the timid input of photoprocessing in late nineteenth century inside Morocco (Muñoz, 2019), is in the early twentieth century when photoprocessing entered completely in the same court of the Sultan, the hand of English and French photographers who were hired to advise and teach the young Abd el-Aziz. Mong the many photographers who came to the court of Sultan des Tacó photographer and videographer who had worked for the Lumière Brothers, Gabriel Veyre. This photographer pointed out that the problem of the change of habits of Sultan Abd el-Aziz, which passed from a distant relationship towards his subjects to a closer treatment. In the aesthetics of power this distance should be greater the higher the position held by the person that was referenced, and in this case, was the Sultan of Morocco. The deal with the European technicians who worked for him and his continuous departures to test motorized vehicles, floats and, even, a small steam train that he brought from Europe and for which he had to install four kilometers of tracks (communicating his two Palaces of Fez), produced “worrying” changes due to its high social position . Among all the technologies that the sultan had brought from Europe and that in those brief years came to the Palace, perhaps the most important in terms of the effects it produced, was photography, exposing it to the criticism of a society as conservative as the Moroccan in As for customs and habits. The Sultan was questioned not only by his people, but also by the power structures of the Mahzen, provoking in 1908 his overthrow in the face of the mutiny of his own brother Abd el-Hafid.

The truth is that each of the Sultan’s exits, each of the visits that he made, for example, from the summer palace to the winter palace, especially when he went alone, caused a great disturbance in the neighborhoods that he disliked to all those who inhabited them. It was a dogma that His Jerifian Majesty, to preserve the full veneration of his subjects, should be shown to them as least as possible (never, so to speak, outside the main holidays of the year, in which the Sultan ceremonies) (Veyre, 1905).

Of these “Christian” imports the most abominable was photography and Hadj had correctly defined the problem since the [photographic] process was an apparent violation of the edict of the Qur’an against the creation of images of human beings, especially believers. Foreign commentators realized the great crime that this caused in Morocco, noting that he ‘raised a simple sin in a heinous crime’ and the traditionalists were “shocked and scandalized” because the Sultan himself should be offended, because his foreign employees were taking these photographs, for him or her own. Avery observed how the local Moors resented seeing their sultan “¡posing here and there as an enthusiastic traveler!” What made the Sultan’s actions even worse was that he, or his experts, photographed the members of his inner circle and even himself and let these images begin to spread in the foreign media. For example, at the end of 1905 an illustrated article about the sultan appeared, including the images of the women of his harem, including a photograph with the caption: “Posing for his master and Lord: Snapshot of the beauties of the harem by the sultan of Morocco: a good example of harem photography by his Imperial Majesty Abdul Aziz of Morocco”. Even the editors of the magazine recognized the crime, pointed out the “revolution” that the Sultan had caused by photographing some of his “innumerable” concubines (there were some 350 women in the harem) and allowing the images to be seen by the unbelievers (Moroccan) (Bottomore, 2008).

Apart from being a reflection of the invisibility of the woman cited by D’Elia (2013), really all this access to technology was a way to distract Abd el-Aziz from his obligations in a period when the powers were dividing Africa. Meanwhile, from the powers the sultan was entertained with all kinds of toys like the same photograph, as Harris warned, “even this has been a means to exploit him” (Harris, 1983), and with this type of practices he catalyzed the discontent from his town.

The consequences of this invasion of foreign experts and devices were serious, especially because these foreigners were of a different religion. At the beginning of the century, a journalist met with a respected and traditional Moroccan, a “Hadj”, who expressed what seems to have been a growing opinion. His description of the concern that this abundance of devices and modern inventions of the Sultan was producing in a still very traditional country (Bottomore, 2008).

Almost parallel to this action there was considerable interest among some French soldiers who were part of the first occupation army and later protectorate. A small part of the photographers who came there belonged to different media, others worked for Les Archives de la Planete (3), which began in those years to photogra-phically inventory the entire planet, introducing the processes of color photography in Morocco, a process recently invented by the Lumière Brothers. Other photographers were military who saw in photography a means of expanding income, or simply developed a creative interest in this medium. The joint work of all these photographers will serve to create an important documentation of the place, not matched later, not even at present, except for the tourist activity, which in many cases has no greater interest than being a reflection of photographs of what we might consider family photographs or snapshots for use in different social networks.

While this was happening in Morocco, the idea that presided over the completion of the inventory, and many others, was presided over by the birth of cinema, sequential photographic image, sending technicians all over the world. In Germany, at the end of the 19th century, a photographer like August Sander began to create the inventory of his society. In Morocco, this inventory was the product of many photographers, although some of them stood out above others, but only a small group personally made an inventory, although they did not perform such an exhaustive work as August Sander’s. Among these notable exceptions of photographers in the Moroccan city of Fez we can name Commander Larribe (reflected in three books published in 1917), or the vast work developed by Marcelin Flandrin (1889-1957) for much of his life, photographers who deserve a deeper investigation of their work.

In this interest to photograph there was a double slope in the work done in this era: on the one hand the military campaign was photographed in all its contexts (parades, marches, camps, meetings with local political elites, interiors of buildings where the military live , some military skirmish, more serious military confrontations of which there is only later evidence); and on the other hand «the indigenous» was photographed as a subject of the protectorate itself (in its buildings through architecture, urban or urbanized landscapes, mosques, festivals, meeting places, cemeteries, street scenes, always through general plans of the natives, a few portraits, some parties, and naked women, probably prostitutes frequented by the occupation troops).

From the twenties of the twentieth century the domination of France over the colony is total, the life is pacified and this is followed by a period of settlement in which thematically it delves deeper into the landscape, as geography outside of politics. The orientation of the photographs is inverted, as had been previously worked, when in the early years of the 20th Century the great military expeditions sought to inventory the territory, whose knowledge was exhaustive in what appeared to be an outpost of everything that came after.

Another photographic change coincides with the political-social change brought about by the Independence of Morocco in 1956, and which necessarily evolved both in subjects to be photographed and in the point of view adopted by the photographers themselves.

The military themes and the female nudes disappear completely, the urban landscape continues to be photographed, which continues to be of interest for the incipient tourism industry, including the human issue, often photographed posing for the photographer or «showing» handmade products valued by tourism. This is when leather tanneries begin to take importance as an almost exclusive theme of Fez, among other issues because of the brightness of their colors, in a first stage of democratization of color among the population. This development in terms of photographic interest coincides with industrial advances in techniques of color photography and photomechanical reproduction, improving on color, although these generally vulgarized the postal medium, obtaining worse results, and that run parallel to a complete banalization of the image. The photographic contexts disappeared in many cases from the images being the backgrounds usually flat, or abusing of objectives of very pronounced focal distances that closed the field of vision (4).

(3) http://collections.albert-kahn.hauts-de-seine.fr/?page=accueil

(4) We cannot leave full record of this fact to not have specific data, however it is easy to infer the success.

This decontextualization we allude to is a deterritorialization, and also a mechanism that contributes to invoke the imaginaries that archetypally form our cultural unconscious. This fragmentation that many travel guides present, illustrative books whose final reader will be a potential traveler, or dreamer, seems to define one of the current photographic practices:

We also speak of multiculturalism that is the reflection of another postmodern concept par excellence, that of fragment. The inhabitants of contemporary cities represent fragments of existing but deterritorialized cultures. Cultures of which we perceive signs and fragments of difference, inscribed in the urban landscape (Garnelo, 2005, p. 47).

Faced with the themes of the early twentieth century referred to above, include topics full of typisms such as the one and scenified in all cases tea time, with themes that directly or indirectly allude to cruelty, idleness, sex, to luxury, bathrooms, odalisques, harem, etc. (Burke, 2001, 162) and that contrast with the current exotic look, in which we can present other photographers who work on the ancient city and that in many cases we should reflect not so much on its themes but on other aspects that we consider of interest and that surely present a certain evolution of the orientalist concept, possibly accommodated to the new historical circumstances.

We thus find a special photographic look towards the traditional themes above any other; we continue to photograph the street and public spaces, crowded, in the approach of travelers or tourists, without delving into the psychological aspects so difficult to deal with in photography. It is the look of the outsider, the one that occurs in all situations, even when the photographer is Moroccan, the approach does not vary in terms of the nuances of the look, probably colonized.

On the other hand there is a way of approaching Morocco, through photographic brushstrokes, in which special lights are used, where the color temperature brings us closer to those orientalist paintings, and in which the saturation of color also leads us to appreciate quasi-biblical sequences, literaturized by scenes where there are no glimpses of any kind of contradiction that can make us participate in a temporary present, in which horizontal time seems stagnant, in the past.

It has been possible to verify that in the editorial photographic realization currently developed by different professionals of photography, and on architectural themes, there are differences with the photographers of the early twentieth century. In general, we appreciate in the few photographs found and always in editorial contexts, how the current photographic context of the photographed places is eliminated in many images. In the current images there is a selection in which the buildings are reduced to certain parts, it is about evoking instead of teaching, this being perhaps one of the signs of construction of the orientalist stereotype, taking into account the functioning of the imaginaries.

The ancient city populated by thousands of tourists invades historical spaces, and indigenous people dressed as in any current street of Spanish or French cities, does not evoke so powerful that imaginary, which needs the coating of timelessness. Something similar happens in exotic literature:

The revealing expressions «Moors of legend» or «warriors of romance» refer inexcusably to an evident process of oriental literaturization. Orientalism thus restructures the entire East under the style and needs of the West. And one of these needs demanded the configuration of the East as «eternal timeless», for which all kinds of cultural and literary references were inescapable (Correa, 2006, p. 182).

Source: 1) Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine and 2) Muñoz, (2012).

Images 1 y 2. Dar Mnebli Palace, Fez, Morocco. 1. Izd.: Pierre Dieulefils (1914); 2. Right: José Muñoz (2009).

5. CONCLUSIONS

Like the film, photography contributes to the fixation and recreation stereotypes, and at times to recover a certain nostalgia. Photography also reinforces that aspect associated with the timelessness of the referent, remaining fixed through time, being nevertheless this one of its structural differences with the cinema, static time in front of the time that flows. The recorded scenarios became timeless about the photographic support, the contexts and the lives of the people as well, as happened in Fez by means of a simple way of «doing» by the operators-photographers, almost always voluntary transmitters but unconscious, of social myths.

The photographed places became places of memory, both for the colonizer and the colonized, who assume their identity as their own, transmitted through photographs that captured the colonizer’s gaze.

In this sense, urban photography prevailed over other less numerous scenarios in front of the representation that was made of the city, urban and architecturally.

REFERENCES

1. Aiger M, Palacín M, Cornejo JM (2013) La señal electrodérmica mediante Sociograph: metodología para medir la actividad grupal. Revista Internacional de Psicología Social: International Journal of Social Psichology, 28(3), 333-347.

2. David P, Johnson M (1998). The Role of Self in Third-Person Effects about Body Image. Journal of Communication, 48(4), 37-58.

3. David P, Morrison G, Johnson M, Ross F (2002). Body Image, Race, and Fashion Models. Social Distance and Social Identification in Third-Person Effects. Communication Research. 29(3), 270-294.

4. Dittmar H, Howard S (2004). Professional hazards? The impact of models’ bodysize on advertising effectiveness and women’s body-focused anxiety in professions that do and do not emphasize the cultural ideal of thinness. British Journal of Psychology, 43, 477-497.

5. Garrido-Lora F (2007). Estereotipos de género en Publicidad. La creatividad en la encrucijada sociológica. Creatividad y Sociedad, 11, 53-71.

6. Karmarkar U, Yoon C, Plassmann H (2015). Marketers should pay attention to fMRI. Harvard Business Review. Recuperado de https://hbr.org/2015/11/marketers-should-pay-attention-to-fmri

7. Kang M (1997). The portrayal of women’s images in magazine advertisements: Goffman’s gender analysis revisited. Sex Roles. A Journal of Research. Gale Group.

8. Lindner K (2004). Images of women in general interest and fashion magazine advertisements from 1955 to 2002. Sex Roles. A Journal of Research, 51, pp. 409-421.

9. Martínez-Herrador JL, Garrido-Martín E, Valdunquillo-Carlón MI, Macaya-Sánchez J (2008). Análisis de la atención y la emoción en el discurso político a partir de un nuevo sistema de registro psicofisiológico y su aplicación a las ciencias políticas. DPSA. Documentos de trabajo del Departamento de Psicología Social y Antropología, 2. Recuperado de http://hdl.handle.net/10366/22533

10. Martínez-Herrador JL, Monge-Benito S, Valdunquillo-Carlón MI (2012). Medición de las respuestas psicofisiológicas grupales para apoyar el análisis de discursos políticos. Tripodos, 29, 53-72.

11. Moreno J (2004). Iconos femeninos. Jordi González lanza el concepto de “marketing sensual”, con el que sale en defensa de la publicidad ante los ataques que ésta recibe por determinados usos de la imagen de la mujer. Anuncios, 1079, 30.

12. Moreno R, Martínez MM (2012). Representación del hombre y de la mujer en la publicidad: análisis de los valores percibidos por el alumnado en función del género del protagonista del anuncio. Actas del I Congreso Internacional de Comunicación y Género. Sevilla, 5, 6 y 7 de Marzo de 2012. Sevilla: Facultad de Comunicación. Universidad de Sevilla.

13. Orzan G, Zara I, Purcarea VL (2015). Neuromarketing techniques in pharmaceutical drugs advertising. A discussion and agenda for future research. Journal of medicine and life, 5(4), 428-432.

14. Reimann M, Castano R, Zaichkowsky J, Bechara A (2012) Novel versus familiar brands: an analysis of neurophysiology, response latency and choice. Marketing letters, 23(3), 745-759. doi: 10.1007/s11002-012-9176-3

15. Sanchez-Porras MJ (2013). Music persuasión in audio-visual marketing. The example of Coca Cola. Historia y Comunicación Social, 18, 349-357. doi: 10.5209/rev_HICS.2013.v18.44333

16. Soloaga P (2007). Valores y estereotipos femeninos en la publicidad de moda de lujo en España. Anàlisi, 35, 27-45.

17. Steele A, Jacobs D, Siefert C, Rule R, Levine B, Marci C (2013). Leveraging Synergy and Emotion In a Multi-Platform World A Neuroscience-Informed Model of Engagement. Journal of Advertising Research, 53(4), 417-430. doi: 10.2501/JAR-53-4-417-430

18. Torreblanca F, Juarez D, Sempere F, Mengual A (2012). Neuromarketing: la emocionalidad y la creatividad orientadas al comportamiento del consumidor. 3Ciencias, revista de investigación. http://hdl.handle.net/10251/34357.

19. Vecchiato G, et al (2014). How to measure cerebral correlates of emotions in Marketing relevant tasks. Cognitive Computation, 6(4), 856-871. doi: 10.1007/s12559-014-9304-x.

20. Wilson R, Baack D, Till B (2015). Creativity, attention and the memory for brands: an outdoor advertising field study. International Journal of Advertising, 34(2), 232-261. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2014.996117

AUTHOR

José Muñoz Jiménez: Professor at the Faculty of Communication Sciences of the University of Málaga. Specialized in documentary photography, cinema and visual anthropology, he has focused his interest on transversal aspects of photography such as identity and memory. He holds a PhD in Audiovisual Communication from the University of Málaga in 2012 with a thesis entitled Exoticism and urban orientalism. He has a degree in Audiovisual Communication (University of Málaga) and in Political Science and Sociology (University of Granada). He has made research stays at the Magnum Agency of Photography in Paris; at the Aix-Marseille University; in the Nejjarine Museum of Fez; at the Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah Fez University; and at the Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona.

josemunoz@uma.es

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7765-0974

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=QOLODDQAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: H-8830-2015