doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.49.81-102

RESEARCH

WOMEN IN THE LEGISLATIVE POWER OF ECUADOR: ANALYSIS FROM VERBAL AND NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION

LA MUJER EN EL PODER LEGISLATIVO DE ECUADOR: ANÁLISIS DESDE LA COMUNICACIÓN VERBAL Y NO VERBAL

A MULHER NO PODER LEGISLATIVO DO EQUADOR: ANALISES DESDE A COMUNICAÇÃO VERBAL E NÃO VERBAL

Geoconda Pila Cárdenas1

Cursa el Doctorado en Comunicación Audiovisual, Publicidad y Relaciones Públicas de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Se ha desempeñado como asesora de comunicación de las Comisiones de Justicia y Biodiversidad de la Asamblea Nacional del Ecuador

1University of Madrid. Spain

ABSTRACT

In this article we analyze the verbal and non-verbal communication of the speeches made during the inauguration of the three main authorities of the legislative power of Ecuador from May 2013 to May 2017. On May 14, 2013 Gabriela Rivadeneira was elected president of the Asamblea Nacional del Ecuador; Rosana Alvarado, first vice president; and Marcela Aguiñaga, second vice president. This parliamentary election has special relevance, because, for the first time in the history of the country, a woman was chosen like first authority of the legislative. Second, at age 29, Rivadeneira became the youngest president of a Parliament in America. Third, it is the first legislature in which 39% of assembly members are women; and fourth, is the first time that three women reach the highest power spaces in this state entity. The verbal analysis describes the main purpose of each discourse and the credible, argumentative and dramatic materials that the speakers use. Regarding the non-verbal band, we observe how the legislators use paralanguage and body language; and what manifestations of affection they transmit. These three speeches represent a significant moment in the achievements of women in Ecuadorian politics and clearly show the styles of communication that each of these assembly members maintained throughout their legislature.

KEY WORDS: political speech, nonverbal communication, discourse analysis, ecuadorian politics, women in politics, verbal communication, legislative power

RESUMEN

En este artículo analizamos la comunicación verbal y no verbal de los discursos pronunciados durante la toma de posesión del cargo de las tres primeras autoridades del poder legislativo de Ecuador del período comprendido entre mayo de 2013 y el mismo mes de 2017. El 14 de mayo de 2013 Gabriela Rivadeneira fue elegida presidenta de la Asamblea Nacional; Rosana Alvarado, primera vicepresidenta; y Marcela Aguiñaga, segunda vicepresidenta. Esta elección parlamentaria tiene especial relevancia, pues, por primera vez en la historia del país, una mujer fue elegida primera autoridad del legislativo. En segundo lugar, con 29 años, Rivadeneira se convirtió en la presidenta más joven de un Parlamento en América. En tercer lugar, es la primera legislatura en la que el 39% de asambleístas son mujeres; y cuarto, es la primera ocasión en que tres mujeres alcanzan los espacios de poder más altos en esta entidad del Estado. El análisis de la banda verbal describe cuál es la finalidad principal de cada discurso y los materiales de credibilidad, de argumento y dramáticos que las oradoras emplean. En la banda no verbal observamos qué uso hacen las legisladoras del paralenguaje y el lenguaje corporal; y qué manifestaciones de afecto transmiten. Estos tres discursos representan un hito significativo en los logros de la mujer en la política ecuatoriana y muestran claramente los estilos de comunicar que cada una de estas asambleístas mantuvo a lo largo de su legislatura.

PALABRAS CLAVE: discurso político, comunicación no verbal, análisis de discurso, política ecuatoriana, mujer en la política, comunicación verbal, poder legislativo

RESUME

Neste artigo analisamos a comunicação verbal e não verbal dos discursos pronunciados durante a toma de possessão do cargo das 3 primeiras autoridades do poder legislativo do Equador do período compreendido entre maio de 2013 e maio de 2017. No dia 14 de maio de 2013 Gabriela Rivadeneira foi eleita presidente da Assembleia Nacional, Rosana Alvarado, primeira vice-presidente; e Marcela Aguiñaga, segunda vice-presidente. Esta eleição parlamentaria tem especial relevância pois, pela primeira vez na história do País, uma mulher foi eleita a primeira autoridade do legislativo. Em segundo lugar, com 29 anos, Rivadeneira converteu-se em a presidente mais jovem do parlamento na América. Em terceiro lugar, é a primeira legislatura na qual 39% da assembleia são mulheres; e em quarto, é a primeira ocasião em que 3 mulheres alcançam os espaços de poder mais altos nesta entidade do Estado. A analises da parte verbal descreve qual é a finalidade principal de cada discurso e os materiais de credibilidade, de argumentos dramáticos que as oradoras empregam. Na parte não verbal observamos que uso fazem as legisladoras da paralinguagem e linguagem corporal; e que manifestações de afeto transmitem. Estes três discursos representam um marco significativo nas conquistas da mulher na política equatoriana e mostram claramente os estilos de comunicar que cada uma dessas mantivera ao largo de sua legislatura.

PALABRAS CLAVE: discurso político, comunicación no verbal, análisis de discurso, política ecuatoriana, mujer en la política, comunicación verbal, poder legislativo

Correspondence: Geoconda Pila Cárdenas. University of Madrid. Spain.

gpila@ucm.es

Received: 14/12/2018

Accepted: 22/02/2019

Published: 15/07/2019

How to cite the article: Pila Cárdenas, G. (2019). Women in the legislative power of Ecuador: analysis from verbal and non-verbal communication. [La mujer en el poder legislativo de Ecuador: análisis desde la comunicación verbal y no verbal]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 49, 81-102. doi: http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.49.81-102

Recovered from http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/565

1. INTRODUCTION

Ecuador is a country that suffered major structural and institutional changes from the adoption of the Constitution of 2008. One of them originated in the articles 65, 70 and 116 of the Constitution that force the Ecuadorian State to promote equal representation of women and men in positions of nomination or appointment of the civil service and take affirmative action to ensure the participation of historically discriminated sectors (Constituent Assembly of Ecuador, 2008, pp. 49 -76).

In this context, the legislative period 2013 - 2017 marked a milestone in the country, in terms of the political participation of women, for several reasons. First, because for the first time a woman was elected president of the Legislative Branch. Second, because Gabriela Rivadeneira, only 29 years old, became the youngest person in Latin America to lead a parliament (Agencia EFE, 2013). On the other hand, three women were simultaneously elected president, first and second vice-president of the National Assembly (Jácome, 2013), something that had never happened before, and, finally, it was the first legislature in which women reached 39% of seats, i.e., almost full parity (Cisneros-Palacios, 2013, p. 4).

This constitutional change responds to a need for the representation of women in politics, since before this period, on average, only 5% of women occupied a seat in Ecuador. For this, the obligation was created that the lists of candidates, presented by the parties and political organizations, should appear in sequence of woman - man or man - woman until reaching all the candidacies (National Assembly of Ecuador, 2009b, p. 28).

On May 14, 2013, Gabriela Rivadeneira was elected president of the National Assembly of Ecuador, Rosana Alvarado, first vice-president and Marcela Aguiñaga, second vice-president. At the time of his election, the three legislators belonged to PAIS Alliance Movement that, in that period, reached 100 of 137 seats (National Electoral Council, 2013, p. 94).

Since this article seeks to emphasize the importance of the participation of women in politics in Latin America, we have reviewed the contributions of María Teresa Piñeiro (2003), Natalia D’Elia (2013), María Teresa Bejarano (2013) and Inmaculada Espizua and Graciela Padilla (2017) who question, for example, whether parity policies are eqivalent to equality or if the use of non-sexist language has a performative nature in gender issues. In addition, they analyze the image of Spanish political women as an element of their communication and female representations in advertising.

For the verbal analysis of Rivadeneira’s inauguration speeches (2013), Alvarado (2013) and Aguiñaga (2013) we use the elements of Aristotle’s Rhetoric (1990), apart from contemporary scholars of the subject such as Felicísimo Valbuena de la Fuente (1997 and 2014), Paula Requeijo (2010), Inmaculada Berlanga, Francisco García and Juan Victoria (2013), Graciela Padilla (2014 and 2015) and Aurora García, Sarai Lagos and María Lourdes Román (2018). This section will identify the kind of speech that each pronounced, its purpose and what materials of credibility, argument and dramatic show.

With regard to nonverbal analysis we will focus on the various elements of paralanguage, kinesics and artifacts, using the categories provided by authors such as Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen (1969), Desmond Morris (1980), Mark Knapp (1992), Fernando Poyatos (1994), Julius Fast (1999), Flora Davis (2005), and the aforementioned academics Valbuena, Padilla and Requeijo. María Elena del Valle (2008) and Jonathan Rodríguez (2018) complement these contributions with a view on clothing as a cultural symbol and clothing as an element of analysis in non-verbal communication.

2. OBJECTIVES

2.1. General

To perform an analysis from the rhetoric and non-verbal language of the speeches of the president and first and second vice-president of Gabriela Rivadeneira, Rosana Alvarado and Marcela Aguiñaga.

2.2. Especific

3. METHODOLOGY

According to official data of the National Electoral Council of Ecuador (2013, pp. 17 and 257), of 137 assembly members elected to the legislative period 2013-2017, 53 are women. The first challenge was to determine which of these 53 women would be analyzed and why. For this we take into account several factors such as legislative work, media visibility, acceptance of management by citizens and popularity in social networks.

These elements, added to the aforementioned milestones, led us to the conclusion that the ideal representatives for this study are precisely the highest authorities of the National Assembly. We decided that the speeches that best suit the needs of this first approach are those of taking possession because they are the only ones that deal with a common theme and have been pronounced by all three in the same session. Subsequently, we determine the categories of analysis that we will use for this study, which we explain below:

3.1. Verbal band

3.1.1. Types of speeches

Aristotle in his work Rhetoric, points out that the discourse consists of three components: the speaker (speaker), the speaker (message) and the speaker (listener). From this last one, it establishes three genres of discourses: deliberative, judicial and epidictic or demonstrative.

Three are in number the species of rhetoric, since so many are the kinds of listeners of speeches that exist. Because the speech consists of three components: the speaker, that what he speaks and that (sic) to whom it is spoken; but the end refers to the latter, I mean, to the listener (...). So, it is necessary that there exist three genres of rhetorical discourses: the deliberative, the judicial and the epidictic. (Aristotle, 1990, pp. 193 - 194)

As for the characteristics that allow us to identify each one, Aristotle (1990, pp. 194-195) He explains that what is characteristic of the deliberative discourse is “consensus and dissuasion”, being its time “the future” and its purpose “what is convenient and what is harmful”. In the judicial discourse, the proper thing “is the accusation or the defense”. Its time is “the past”, while its purpose is the “just and the unjust”. Finally, the demographic discourse is characterized by resorting to “praise or censorship”. Its most appropriate time “is the present” and the purpose pursued is “the beautiful and the shameful ”.

3.1.2. Purpose of the speech

As for the “what the speaker is talking about” or the purpose of the speech, Professor Felicísimo Valbuena de la Fuente points out that there are nine purposes: to inform, to expose, to influence an audience, to convince, to inspire or motivate, to stimulate, to obtain an action, to persuade, and to praise or vituperate (Valbuena, 1997, pp. 521-558).

3.1.3. Rhetorical materials

As final section of the verbal band of the selected speeches we will analyze the rhetorical materials. Aristotle proposes three species of evidence by persuasion:

Among the evidence for persuasion, those that can be obtained through discourse are of three species: some reside in the mood of the speaker, others in predisposing the listener in some way and, the last ones, in the discourse itself, thanks to what this shows or seems to show (1990, p. 175).

These “species of proofs by persuasion” are known (and thus will consist in later references) as: materials of credibility or ethos, materials of argument or logos, and dramatic materials or pathos.

Aristotle shows them that, by their origin, there are inartistic proofs or “alien to the art”, which means “that they existed beforehand”; and other artistic or “art-specific”, which means “that they can be prepared by method and by ourselves” (1990, p. 174).

3.2. Non-verbal band

Mark L. Knapp (1992, p. 41) explains that “The nonverbal term is commonly used to describe all events in human communication that transcend words spoken or written”. Such is its importance in the framework of communication understood as an integral phenomenon, that Ray Birdwhistell affirms that: “No more than 35 percent of the social meaning of any conversation corresponds to the spoken words” (Davis, 2005, p. 42).

Those who study nonverbal communication have agreed that this has seven areas: kinesics, physical, tactile behaviors, paralanguage, proxemics, artifacts and environment, but it should be noted that this work will be limited to the analysis of three of them: paralanguage, kinesics and artifacts.

3.2.1. Paralanguage

Although authors like Fernando Poyatos (1994, p. 28) provide very detailed definitions of the the paralanguage and its components, this category of non-verbal communication can be summed up in this sentence: “refers to how something is said and not what is said” (Knapp, 1992, p. 24). Paula Requeijo (2010, p. 266) includes pauses and errors in speaking in this category; however, citing Trager, both Humberto Eco (1986, p. 11) and Knapp (1992, pp. 24-25), they agree that the components of the paralanguage are:

3.2.2. Kinesics or body language

Ekman and Friesen (1969) classified the elements of kinesics in the following:

3.2.3. Artifacts

They understand the manipulation of objects with interacting people that can act as non-verbal stimuli. These artifacts include perfume, clothing, lipstick, glasses, wigs and other objects for the hair, false eyelashes, eye paints and all the repertoire of hairpieces and beauty products (Knapp, 1992, p. 25).

To facilitate the development of the work, we transcribe in full the three discourses, which texts are part of this article as annexes. In addition, the videos of these interventions can be seen from the links that appear in the bibliography.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Gabriela Rivadeneira: speech of inauguration of the position of president of the National Assembly of Ecuador

With 107 affirmative votes, of 137 assembly members, Rivadeneira was named president of the National Assembly of Ecuador, for a period of two years.

4.1.1. Verbal band

4.1.1.1. Type of speech

This is a demonstrative or exhibition speech. As you can see, there is a recurrence to the present, praise and reprobation in the minutes: 00:25, 04:30, 07:33 and 02:07. An example of time management is the following: “Today we inaugurate a new stage in the history of Ecuador” (Rivadeneira, 2013, minute 00:25).

4.1.1.2. Purpose of the speech

The purpose that Gabriela Rivadeneira pursues is “to inspire or motivate”, since, as Valbuena points out, in this case the “emotion” has the main role and “the greatest secret of their effectiveness is that they are brief”. (Valbuena, 1997, pp. 521-558)

4.1.1.3. Rhetorical materials

4.1.1.3.1. Credibility or ethos materials

They refer to the character of the speaker or the qualities that allow her to present herself as a reliable, competent and dynamic person (Valbuena & Padilla, 2014, pp. 271-302); but also, they include features that allow her to attack their opponents or fend off attacks that these formulate to her. An example of the first use is this:

As for me, a twenty-nine-year-old woman, wife, mother of two sons who comes from a small but wonderful city, who has inherited hundreds of struggles and resistance, Otavalo, belonging to the province of Azul de los Lagos, I assume the challenge recognizing the historical and persevering struggle of millions of women and young people throughout the ages (Rivadeneira, 2013, minute 06:36).

(1) Imbabura is the real name of the province.

While attacking his political contenders when he points out: “The era in which the legislative power of Ecuador served particular interests, is over. Today the Assembly is representative of each region and each territory of the country” (Rivadeneira, 2013, minute 05:03).

4.1.1.3.2. Argument materials or logos

One of the few inartistic proofs that is observed, as a constant, in the speech of Rivadeneira is the popular vote as evidence that her designation and that of her entire political store, is legitimate and has support: “Today we inaugurate a new stage in the history of Ecuador, a stage that began on February 17, 2013, day in which the Ecuadorian people decided to ratify at the ballot box the citizen’s revolution as a national project”. (Rivadeneira, 2013, minute 00:24).

In contrast, this discourse is rich in artistic evidence, precisely because of her purpose to “inspire or motivate”. Some of the resources most used by the Assemblywoman are the enumeration (fifteen times) the use of images or allegories (three times), and contrast figures (nine times).

4.1.1.3.3. Dramatic materials or pathos

To this type of arguments also belong the inartistic tests. In this space we will focus on the analysis of the comparison, which is one of the most important dramatic resources used by Gabriela Rivadeneira.

Although it is clearly seen only twice (6:54 and 8:05 minute minute), this material is important because she manages to fix in the mind of the recipient l idea that the appointment of a woman as president of the legislature is as important as the first woman who dared to vote or legislate:

I take up the challenge by recognizing the historical and persevering struggle of millions of women and young people throughout the ages. I assume it with responsibility, simplicity and absolute firmness, as Matilde Hidalgo did eighty-nine years ago, who, with her tenacity, was the first woman to give a popular vote, and of Nela Martínez who, with her passion and political action, was the first legislator of Ecuador (Rivadeneira, 2013 , minute 06:54).

4.1.2. Non-verbal communication

4.1.2.1. Paralanguage

One of the first elements that is appreciated is the time, which in her case is quite balanced. In general, the legislator has a clear voice range and a correct articulation of the words. Regarding the vocal qualifiers, Rivadeneira shows a soft tone of voice, with slight variations in intensity when she wants to emphasize the idea of how disastrous the country’s political past was.

In addition, despite having lived in Otavalo, a mostly indigenous city, she does not show the characteristic accent of this area, which includes dragging the execution of certain phonemes such as /?/ (lateral palatal), /j/ (proximal palatal) or /?/ (sonorous palatal fricative), turning them into /?/ (fricative postalveolar unvoiced). Occurs something similar with phonemes /?/ (alveolar simple vibrating) and /r/ (alveolar multiple vibrating) that transform into /?/ (sonorous retroflex fricative). Rather, her accent shows a clear influence of the way of speaking of Quito, the capital of the country.

4.1.2.2. Kinesics or body language

The main baton used by Rivadeneira is to move the head up and down as a sign that she is agreeing. She uses this baton 129 times and, in most cases, its use coincides with the pauses. Another of the most recurrent batons is to move the head to one side, in an almost childlike gesture of seeking approval from the audience. She performs this act 36 times.

Also on one occasion he moves his head back, justly illustrating that idea and only in two moments (minute 1:32 and 05:58) Rivadeneira uses his hands to illustrate r, one of them is when she says: “A rebel people came to mess everything up, to question everything and to reinvent (baton) everything” (Rivadeneira , 2013 , minute 01:32). Here she is observed that she uses the index finger and raises it vertically four times. Like Morris (1980, p. 61) explains: “she acts as a symbolic club or stick prepared to fall on someone”. In this case, it represents the “citizen power”, the power of the “people” ready to fall on those who are against the change.

The main manifestation of affection is joy. Rivadeneira shows a smile on different levels, although the most common one is with the lips and teeth separated, the mouth extended to the sides and the cheeks elevated. However, this emotion does not present itself in a pure state, because at times there are traits of sadness or anger. Anger, for example, is expressed for a brief moment when it says: “For a long time our country did not enjoy peace, development, stability and well-being as it has now” (Rivadeneira, 2013, minute 00:57).

Finally, Gabriela Rivadeneira’s most obvious self-adapter is to moisten her lips by placing her tongue between them. During his speech he does it 21 times, which indicates a certain nervousness. The assemblywoman only registers an object adapter that consists of arranging the papers of her speech. She performs this action only once.

4.1.2.3. Artifacts

During Rivadeneira’s speech there are three artifacts that stand out for the message they convey: the speaker’s identification with the indigenous. It’s about the blouse, the earrings and the hairstyle. The white blouse with pleats and with the neck and sleeves embroidered by hand (Jaramillo, 1990, p. 138) It is a westernized version of the blouses made by the indigenous women of the community of Zuleta that are used in Otavalo. It is green because it seeks to establish a link with the color of its political party. It also uses long golden earrings, with a spiral at the end, an Andean symbol that represents a cyclical conception of time (Miranda-Luizaga, 2007, p. 71). Finally, her hairstyle is a braid that collects the hair completely what recalls the pigtail wrapped in a ribbon -called huango- that is characteristic of indigenous women of Otavalo (Jaramillo, 1990, p. 139).

4.2. Rosana Alvarado: speech of inauguration of the position of first vice-president of the National Assembly of Ecuador

Alvarado is a communicator and lawyer. In addition, she has focused her political efforts on the struggle for women’s rights, promoting controversial issues such as the decriminalization of abortion and the criminalization of femicide as an aggravated crime, which has generated criticism from the most conservative sectors of the country.

4.2.1. Verbal band

4.2.1.1. Type of speech

This is a judicial speech in which two characteristic elements are present: the past time and the accusation. The assemblywoman begins with a description of the identity of people that belong to the South of Ecuador, from where she is, and immediately accuses in the past tense:

And to this people, a lover of preciosity, to these women of candongas (2), to these women of ikat (3) came the scourge of the colony, of slavery, of infamy. One master came after another and another. They expelled our people, they plundered our riches. Gold, silver, savings, all migrants, all exiled (Alvarado, 2013, minute 01:23).

(2) Silver or gold earrings characteristic of the dress of the Cholas Cuencans. See Astudillo (2012). Astudillo (2012).

(3) Technique of tissue practiced in Gualaceo, province of Azuay. See Beltrán (2015).

4.2.1.2. Purpose of the speech

Alvarado’s speech has at least three purposes that manifest themselves at different times. She starts her short intervention (5 minutes and 58 seconds) with a set of images (minute 01:58) that have the effect, above all, of moving, that is, at this stage her speech has the purpose of “inspiring or motivating” However, not only emotionality governs such presentation. The objective of the legislator is also to “praise or reproach”, although a more just word would be to accuse. Finally, the assembly member seeks to “convince” her listeners about an idea that, as said, has been her main political banner: gender equality. Alvarado places great emphasis on the great achievement of having 40% of women in Parliament and that its three main authorities are also women.

4.2.1.3. Rhetorical materials

4.2.1.3.1. Credibility materials or ethos

Alvarado uses this type of material, fundamentally, to attack her contenders. In fact, in all the speech hardly two affirmations of her ethos are identified (minute 00:09 and 05:13) and no defense.

At the other extreme, practically half of his discourse is credible material that he uses to attack his political contenders and judge the “historical oppressors.” One of the clearest examples It is the following:

They tried to leave eternal the domination and subjection. Here, who today spoke of respect, of democracy, of respect for fundamental rights. In this plenary hall, and in front of this mural of the master, of the unattainable Guayasamín, they voted for submission, they voted mortgaging the country, here, to the International Monetary Fund, to the cannibal banking. They handed over national territory to foreign bases (Alvarado, 2013, minute 02:49).

4.2.1.3.2. Argument materials or logos

The speech of Rosana Alvarado is, to a great extent, emotional, for this reason there is no greater use of inartistic proofs. Despite this, we quote the following paragraph as the best example of the use of this type of material: “The Congress of the partidocracy from the year 94 to 96 left women with 4.94% participation. The Congress of the partidocracy from the years 96 to 98 allowed the participation of only 3% of women”. (Alvarado, 2013, minute 03:56).

4.2.1.3.2. Dramatic materials or pathos

This is perhaps one of the sections of the rhetoric in Alvarado’s speech. Practically all the intervention is impregnated with images and allegories (minutes 00:09, 00:36, 00:53 and 01:58); repetition (minutes 00:53, 1:23, 1:38, 2:54, 3:42, 3:56, 4:39, 4:56 and 5:14), enumeration (00:09 minutes, 00: 37, 1:02, 1:29, 1:49, 1:58, 2:54, 5:14 and 5:44) and figures of contrast (1:23 minutes, 2:54 and 4:56) that constitute artistic proofs created by the speaker to move the passions of her audience.

For reasons of space, we only mention one example of the use of images and allegories: “The most delicate, dazzling filigree in singing candongas, peacocks, baskets or enameled gold. As if gold, by itself, were insufficient”. (Alvarado, 2013, minute 00:36).

4.2.2. Non-verbal communication

4.2.2.1. Paralanguage

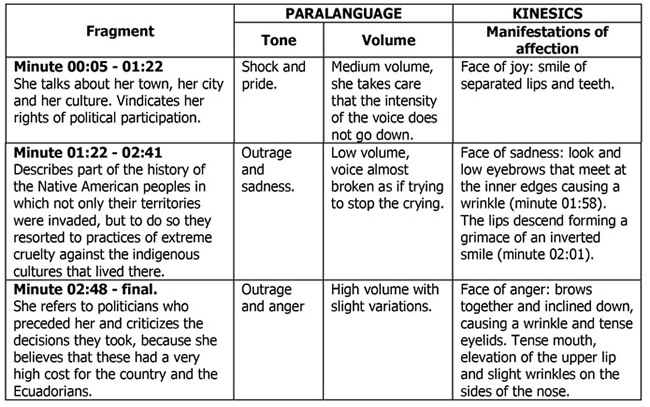

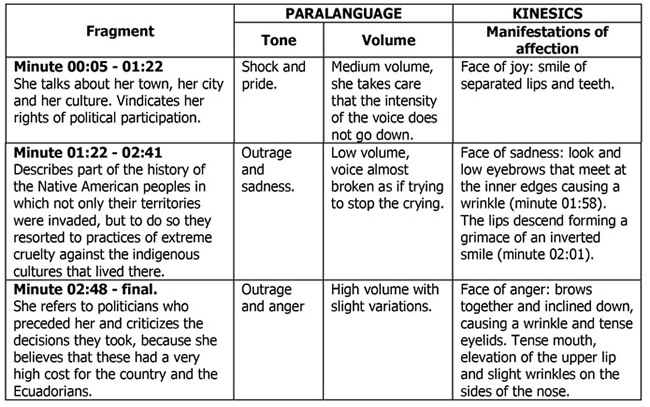

The time of the intervention of Rosana Alvarado is quite balanced and highlight three of the vocal qualifiers that are: tone, volume and extension. We have divided the intervention into three moments to analyze the tone, volume and manifestations of affection:

Table 1. Comparative chart of tone, volume, and manifestations of affection.

Source: own elaboration.

Finally there is the extension that:

In the case of Rosana it involves dragging the phonemes /?/ (alveolar simple vibrant) and /r/ (alveolar multiple vibrant), in her speech it becomes /?/ (sonorous retroflex fricative), i.e., in a very marked r. Like the melodious tonal field, this particular way of dragging the words is widespread in the inhabitants of this city, although it is also present, with slight variations, in other areas of the Ecuadorian highlands (Pila, 2018, p. 339).

The first vice-president also extends the words she wants to emphasize, this is particularly noticeable when she pronounces the fragment of Bulletin and elegy of the mitas, a poem by the Cuenca writer César Dávila Andrade (Alvarado, 2013, minute 01:58).

4.2.2.2. Kinesics or body language

In Alvarado’s speech two types of illustrators are mainly observed: batons and pointers the batons conductors of Alvarado are two, with head and face: to lift her eyebrows (47 times) and movement of the head up and down (43 times).

Also h ace 35 repetitions of the baton raised index finger, with hand movement up and down. This baton has two variations that are palm side, with hand movement up and down (8 repetitions); and palm up, with hand movement up and down (once). Marginally, the following conductors also appear: index finger raised with circular motion (once), palm side with movement from side to side (once) and grasp of vacuum (once).

Cuencan assembly member also employs three pointers during intervention: forefinger extended with downward movement (8 times), thumb raised with back hand movement (7 times) and forefinger raised pointing up (3 times). One of the regulators that is appreciated in this speech is that of applause. This regulator appears seven times in the minutes: 02:41, 03:18, 03:46, 04:27, 05:10, 05:31 and 05:55. Another regulator appears at the end of the intervention, when the legislator says: “¡Long live the homeland!” to conclude. The audience, shouts “¡Long live!”, with this response the receivers, once again, show their active interest and support to the speech of Alvarado.

The legislator uses the adapters 13 times, 9 of which are self-adapters and 4, object adapters. The self-adapters that are observed are to fix her hair with a movement of the head (four times), to place the hair behind the ear with the hand (once) and to to lick her lips (four times). We observe only one object adapter that consists of accommodating the speech sheets on the lectern, which occurs four times.

4.2.2.3. Artifacts

In this presentation, Alvarado appears with a violet silk dress or some material with similar texture. It is a fairly conservative but elegant cut that covers your body up to your neck. However, what really stands out in this section is bulky wearing pearl necklace, which at first glance looks like an artifact, but actually emulates an Indian jewel known as gualca. Although the Cuencan Cholas -indigenous women from the city of Alvarado’s origin- do not usually use this type of jewel, it is important to point out that the assembly member wanted to establish a link between her mixed racial ancestry condition (the dress) and her pride of the indigenous.

(4) Necklace composed of several rows of glass, plastic or coral beads traditionally used by indigenous women in the Ecuadorian highlands.

4.3. Marcela Aguiñaga: speech of inauguration of the position of second vice-president of the National Assembly of Ecuador

Marcela Aguiñaga is a lawyer from the city of Guayaquil, the most populous in the country and a referent for the development in the coastal region. Prior to being an assembly member, Aguiñaga served as Minister of the Environment in the period between November 2007 and November 2012, being the Secretary of State that was the longest in that portfolio in the Government of President Rafael Correa.

4.3.1. Verbal band

4.3.1.1. Type of speech

Se trata de un discurso deliberativo. Aunque Aguiñaga no usa directamente el futuro como tiempo verbal, continuamente hace llamados, a la ciudadanía a y sus compañeros legisladores, que solo se pueden concretar en el futuro.

4.3.1.2. Purpose of the speech

This speech primarily aims to “convince”. As it is observed, in this case the main resource is the “reasoning”, while the emotion -unlike what happens with the interventions of Rivadeneira and Alvarado- has a marginal role (Valbuena de la Fuente, 1997, pp. 521 -558).

4.3.1.3. Rhetorical materials

4.3.1.3.1. Credibility or ethos materials

The only time she talks about her credibility materials in the first person of the singular is the following: “I receive this assignment from you, fellow members, grateful, but with the firmness and conviction necessary to face the challenge with transparency, with firmness and with honesty”. (Aguiñaga, 2013, minute 04:00).

On the other hand, also on its own, the credibility material that was identified as an attack on its political contenders is the following: “Today an assembly member, who now says to defend nature, visited my office when I was Minister of the Environment, asking for the illegal miners. That is what is represented, that is the past that must be left behind”. (Aguiñaga, 2013, minute 03:19).

4.3.1.3.2. Argument materials or logos

We find three argument materials or logos (in minutes 00:53, 02:06 and 03:19) that correspond to what Aristotle calls inartistic proofs. We quote the following example: “There are urgencies that we must face and we are, perhaps, facing the only opportunity to exercise legislative management without petty blockages as in the past” (Aguiñaga, 2013 , 02:06) . We quote this fragment because in that period, the PAIS Alliance Movement obtained a solid majority composed of 100 of 137 legislators.

4.3.1.3.3. Dramatic materials or pathos

The speech of Aguinaga is fundamentally rational, so greater use of dramatic material is not observed. The main resource that it uses is the enumeration (four times). In a marginal way, we find the repetition (twice) and the use of images and allegories (once). We quote the following example because it is the one that best picks up the idea of pathos: “Today crystallizes one of the yearnings long awaited by a country that in the past six years has been characterized by demolishing myths and promote inclusion and equity, two concepts that were once despised by the political class” (Aguiñaga, 2013, minute 00:30).

4.3.2. Nonverbal communication

4.3.2.1. Paralanguage

As for the time, there is no difference between Marcela Aguinaga and her fellow legislators, since all three show a balanced time suitable for the situation, the scenario and the type of audience they have. In relation to the vocal qualifiers, the tone of the representative of the province of Guayas, which is almost the same throughout all the intervention, is fundamentally professional, politically correct and little confrontational. Related to the above, we find that Aguiñaga shows a medium volume, almost without variations throughout his intervention.

The only variation that we find, both in the tone and in the volume of Aguiñaga, occurs when she talks about the visit she received, as Minister of the Environment, by a legislator present in the room, to advocate in favor of illegal miners (minute 03:19) that was already mentioned before. In this fragment of the speech, Aguiñaga’s tone changes to indignation and reproach; and to ratify this feeling, the volume of his voice rises a little.

Regarding the extension, due to its characteristic Ecuadorian coast accent (in general, similar in the Spanish-speaking Latin American tropics), the speaker cuts the words, especially those that have the phoneme /s/ at the end syllable as, for example somos, characteristics, among others. If attention is paid, what actually happens is that she replaces the phoneme /s/ (voiceless alveolar fricative) with the phoneme /x/ (low-sounding velar fricative), with which the above words sound: /?somox/, /karakte?rixtikax/. Although, for an ear unaccustomed to this way of speaking, it would seem that the phoneme /s/ is directly omitted.

4.3.2.2. Kinesics or body language

Generally speaking, Marcela Aguinaga makes very little use of the hands, for this reason, most of the gestures corresponding to the section of illustrators are produced with the head. In this speech, the assembly member exhibits basically three types of illustrators: batons, pointers and ideographs.

The conductors are present in two ways: movement of the head up and down (61 repetitions) and index finger raised with hand movement up and down (6 repetitions). Because the second baton is a signal of censure or reproach, the assemblywoman uses it only when she refers to the only clearly negative theme of her speech: the visit of the legislator who advocated illegal mining.

Aguiñaga uses pointers in three moments; the first is when she refers to her teammates Gabriela Rivadeneira and Rosana Alvarado, who are already on the main podium. The second is when referring to the Assemblyman (present in the room) that visited her to advocate for illegal mining. The third moment occurs at the end, when the speaker says goodbye to the audience. Aguinaga utters the phrase: “Thank Ecuadorian people” and pointed with his hand towards the high bar, where people are, with the hand pointer raised with the palm back once.

Also, she uses the ideographs on two occasions, in 3:16 and 3:29 minutes. Both mark the idea of time: “That is what is represented, that is the past that must be left behind (ideograph)” (Aguiñaga, 2013, 03:29). In both cases, the ideograph used consists of raising the index finger pointing back.

On the other hand, we identified three samples of affection: joy, anger and surprise. As we know, laughter and smiling are the main gestures of joy. We believe and this is one of the manifestations of affection present in the speech of Aguinaga, because before starting his speech, she showed a big smile characterized by a grimace of parted lips and teeth together, but visible, which raises the cheeks and wrinkle slightly the eyelids, which create the effect of making smaller the eyes.

Despite the intensity of this first gesture, then only timid but constant smiles are appreciated throughout the presentation. This kind of smiles appear in the seconds 00:16, 00:19 and 00:47; and in the minutes 01:02, 01:20, 01:29, 02:44, 03:24 and 03:29. In general, it is observed that the moments of joy of Aguiñaga are related to her appointment as legislative authority, with the political achievements of women and with the positive changes that, from her point of view, have occurred with the “citizen revolution”.

In contrast, anger appears mainly in the upper part of the face, especially the eyebrows, which come closer and tilt down causing a wrinkle between them. The eyelids and tense mouth accompany this manifestation of affection that -as happened with joy- in the case of Aguiñaga, is not shown intensely. This manifestation of affection appears associated with verbal components that represent a negative idea for her as follows: “There are emergencies that we must face and we are, perhaps (eyebrows of anger), at the only opportunity (eyebrow of anger) to exercise a legislative management without petty blockages as in the past” (Aguiñaga, 2013, minute 02:05).

The surprise appears, however, when she recounts the visit made by an assembly member present in the room, when she was Minister of the Environment, to advocate for illegal mining. This show of affection is expressed in what is called surprise eyebrow, which consists of elevating this part of the face more than usual, which produces long horizontal wrinkles on the forehead, as indeed it is observed in the face of the speaker in the minutes 03:15 and 03:19.

The applause is the only regulator that is appreciated in the presentation of the legislator from Guayaquil, and these appear as a response from the receivers only twice, in the minutes 03:19 and 03:30, precisely when the speaker improvises, what shows that it is the best moment received by her audience.

The body language of the Legislator shows tranquility and absence of nervousness for most part of the speech. The only self-adapter that we observe is to set the hair with the movement of the head, 15 times. Although 15 times seem many, if you watch the video carefully, it is noticed that this gesture is more related to the discomfort that produces his hair (because his hair falls several times to his eyes) with a state of nervousness. In the speech of the legislator, only two object adapters are appreciated: to touch the microphone (once) and to keep the sheets (twice).

4.3.2.3. Artifacts

Aguinaga, in contrast to the dress chosen by her companions, appears in a completely western attire, composed of a formal suit of jacket and dark gray skirt, a blue blouse and a long necklace that cuts the simplicity of the blouse. In this set of garments there are no elements that can be associated with an indigenous culture (as in the case of Rivadeneira and Alvarado) or traditional Ecuadorian coast. On the contrary, it seems that the assemblywoman seeks to show her true personality and even marks distance of the characteristic color of her political party, the green one.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The most remarkable thing in Gabriela Rivadeneira is the rhetorical construction of her speech, since it is full of images and allegories that manage to move the receptors throughout the entire intervention, despite this, she has a monotonous body language. It is noticed that there was a previous rehearsal, nevertheless, she shows her nervousness by means of the repetitive use of the self-adapter that consists of moistening her lips by placing the tongue between them. Of the three women in the legislative power, she is the one that transmits the most meaning through the artifacts.

Rosana Alvarado is the speaker who achieves the best result by analyzing verbal language and non-verbal communication as a whole. Her speech is fundamentally emotive, since she uses dramatic materials that are very moving throughout his speech. In general, her body language demonstrates mastery of the situation and reflects her experience as a speaker. Her gestures convey naturalness to the receiver and her true commitment to the words she utters.

Marcela Aguiñaga differs from her colleagues by showing a professional and polished style in her way of communicating. Her speech is marked by rational rather than emotional elements. Constantly, the legislator shows that her political origin is not that of the popular election but the management and technical work. Of the three speakers, she is the one that used the least amount of credibility materials, both for the defense and for the attack, which marks the distance between her and the style of praising and blaming her companions.

The three legislators seek to project the identifying features of gender and the culture they represent. Although the three seem to have different styles of communication, in reality they form a whole that complements each other. Together they represent three of the most important regions of the country (northern and central highlands, the southern highlands and the coast), which makes them an articulating element in the midst of physical and cultural distances.

REFERENCES

1. Agencia EFE. (2013, octubre 11). Gabriela Rivadeneira, la encarnación de la revolución ciudadana. El Tiempo. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2LSEfPq

2. Aguiñaga M (2013). Discurso de toma de posesión como segunda vicepresidenta de la Asamblea Nacional del Ecuador. Ecuador: Televisión Legislativa. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2OkQgi5

3. Alvarado R (2013). Discurso de toma de posesión como primera vicepresidenta de la Asamblea Nacional del Ecuador. Ecuador: Televisión Legislativa. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2v9VZP9

4. Aristóteles (1990). Retórica. Madrid: Editorial Gredos.

5. Asamblea Constituyente del Ecuador. Constitución de la República del Ecuador (2008). Ecuador: Registro Oficial No. 449 del 20 de octubre de 2008. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2LVz1Tf

6. Asamblea Nacional del Ecuador. Ley Orgánica Electoral y de Organizaciones Políticas de la República del Ecuador - Código de la Democracia (2009). Ecuador: Registro Oficial No. 578 del 27 de abril de 2009. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2v9dUpf

7. Astudillo G (2012). La candonga ya no es una joya exclusiva de la chola cuencana. El Comercio. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2M52slP

8. Bejarano M (2013). El uso del lenguaje no sexista como herramienta para construir un mundo más igualitario. Vivat Academia, 124, 79-89. Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/191

9. Beltrán J (2015). El Ikat es el nuevo patrimonio inmaterial del Ecuador. El Comercio. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2uZqg3Z

10. Berlanga I, García F, Victoria J (2013). Ethos, pathos y logos en Facebook. El usuario de redes: nuevo «rétor» del siglo XXI. Comunicar, 41, 127-135. https://doi.org/10.3916/C41-2013-12

11. Cisneros-Palacios F (2013, junio). Paridad y representación en la nueva Asamblea Nacional. Opinión Electoral. Gaceta de análisis político electoral, pp. 4-5. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2uQ2SWs

12. Consejo Nacional Electoral (2013). Resultados Electorales. Elecciones Generales 2013. Quito. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2uUS0qe

13. D’Elia N (2013). La mujer en la política: ¿igualdad o diferencia? Una invitación a la reflexión. Revista de la SEECI, 32, 31-40. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2013.32.31-40

14. Davis F (2005). La Comunicación no verbal (8a reimp.). Madrid: Alianza.

15. Del-Valle M (2008). Aproximación a la indumentaria como símbolo cultural: un recorrido histórico. Revista de la SEECI, 16, 74-97. Recuperado de http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/177

16. Eco H (1986). La estructura ausente. Barcelona: Editorial Lumen.

17. Ekman P, Friesen W (1969). The repertoire of nonverbal behavior: Categories, origins, usage, and coding. Journal of the International Association for Semiotic Studies/Revue De l’Association Internationale, 1, 49-98.

18. Espizua I, Padilla G (2017). La imagen y el estilo de la mujer política española como elementos básicos de su comunicación. Revista de la SEECI, 42, 62-84. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2017.42.62-84

19. Fast J (1999). El lenguaje del cuerpo (15a ed.). Barcelona: Kairós.

20. García A, Lagos S, Román M (2018). Constitución española en la columna “Escenas políticas” de Campmany. Vivat Academia, 144, 51-67. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2018.144.51-67

21. Jácome J (2013, mayo 14). Tres mujeres dirigen ya la Asamblea Nacional. Ecuador en vivo. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2LqEQf8

22. Jaramillo H (1990). La indumentaria indígena de Otavalo. Sarance, 14, 127-144. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2mMhDW1

23. Knapp M (1992). La comunicación no verbal. El cuerpo y el entorno. Barcelona: Paidós.

24. Miranda-Luizaga J (2007). Categorías filosóficas del pensamiento andino. En Acconero M (Ed.), El arte y el diseño en la cosmovisión y pensamiento americano (pp. 71-74). Códoba: Editorial Brujas. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2LqlUwY

25. Morris D (1980). El hombre al desnudo: un estudio objetivo del comportamiento humano. Barcelona: Ediciones Nauta.

26. Padilla G (2015). La espectacularización del debate electoral: estudio del caso en Estados Unidos. Vivat Academia, 132, 162-181. Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/587/130

27. Pila G (2018). Componentes verbales y no verbales en tres tipos de discursos: análisis de casos. En Vega-Baeza R, Requeijo-Rey P (Eds.), La Universidad y nuevos horizontes del conocimiento (pp. 333-347). Madrid: Editorial Tecnos.

28. Piñeiro M (2003). Representaciones femeninas en la publicidad. Una propuesta de clasificación. Revista de la SEECI, 10, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2003.10.1-16

29. Poyatos F (1994). La comunicación no verbal II. Paralenguaje, kinésica e interacción (Primera Ed). Madrid: Ediciones Itsmo.

30. Requeijo P (2010). El estilo de comunicar de Barack Obama. CIC Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación, 15, 263-285.

31. Rivadeneira G (2013). Discurso de toma de posesión como presidenta de la Asamblea Nacional del Ecuador. Ecuador: Televisión Legislativa. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2Ad3yu3

32. Rodríguez J (2018). Estudio en cognición social: el vestuario y su vinculación como elemento de análisis en la comunicación no verbal. Vivat Academia, 143, 85-110. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2018.143.85-110

33. Valbuena-de-la-Fuente F (1997). Teoría general de la información. Madrid: Noesis.

34. Valbuena F (1997). Comunicación Institucional (II): Presentaciones y Debates. En A. El-Mir & F. Valbuena (Eds.), Manual de Periodismo (pp. 521-558). Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Prensa Ibérica.

35. Valbuena F, Padilla G (2014). Los debates políticos televisados. En Herrero J, Max R (Eds.), Comunicación en campaña. Dirección de campañas electorales y marketing político (pp. 271-302). Madrid: Pearson.

AUTHOR

Geoconda Pila Cárdenas: Attends the doctorate in Audiovisual Communication, Advertising and Public Relations at the Complutense University of Madrid. Master’s Degree in Political and Business Communication from Camilo José Cela University of Madrid. Degree in Social Communication by the Central University of Ecuador y best graduate of his class. She has been a political communication advisor in the Commissions of Justice and Structure of the State; and of Biodiversity and Natural Resources in the National Assembly of Ecuador, where she has worked directly with its presidents.

gpila@ucm.es

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2624-4543

Google Scholar: http://bit.ly/2UDxHsN

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Geoconda_Pila_Cardenas

ResearcherID: http://www.researcherid.com/rid/L-7355-2018