doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.49.159-174

RESEARCH

SOUNDTRACK AND IDENTITIES IN THE GENERATION “Y”

BANDA SONORA E IDENTIDADES EN LA GENERACIÓN “Y”

BANDA SONORA E IDENTIDADES NA GERAÇÃO “Y”

Josep Gustems Carnicer1

Profesor titular de Didáctica de la Expresión Musical en la Universidad de Barcelona. Dr. en Pedagogía, docente en Comunicación Audiovisual y autor de un centenar de libros y artículos científicos sobre la música, la educación y la comunicación

Diego Calderón Garrido2

Adrien Faure Carvallo1

Alba Montoya Rubio1

1University of Barcelona. Spain

2International University of La Rioja. Spain

ABSTRACT

Television has had an undeniable importance in the 90s in Spain, especially for children and young people who belong to the so-called generation “Y” or “Millennials”. This age has grown in parallel with domestic technology and social networks, making audiovisual environments their natural habitat. In this context, the television series of animation of that time caused a great influence in this generation that was then growing and learning. Our study aims to analyze the sound characteristics of the openings of the 20 cartoons of children’s animation most seen in Spanish television in the 90s. This analysis will be done by applying a sound-music template validated and used in previous research by other authors. With all this, we characterize the sound landscape that accompanied this generation in its infancy, distinguishing between different sound profiles. To do this, the presence or absence of certain sound and musical elements, original or manipulated by postproduction techniques, aimed at different audiences according to sex, age, emotions, motivation for technology or social relationships are analyzed. So, it is proposed to deepen and sustain the heterogeneity present in the individuals of this generation, fleeing from homogenizing clichés, enabling different ways of approaching their social identity and the richness they represent for current Spanish society, based on the sound that accompanied them and marked in their childhood.

KEY WORDS: soundtrack, animation series, millennials, music, sound, children’s television, identity

RESUMEN

Desde los comienzos del cine, en los que una sola persona se ocupaba prácticamente de todo, la organización de la creación de un film fue evolucionando, y las diversas funciones del proceso fueron aumentando y especializándose progresivamente. La noción de autoría colectiva es un concepto difícil de abordar y de comprender en toda su dimensión. En este artículo se pretende analizarlo, tras estudiar de qué modo la estructura de colaboración en equipo de aquella época influía en sus creadores, y por qué razón se considera que unos son autores, mientras a otros se les niega esa condición. Para examinar a fondo cuál era el sistema de trabajo real de los distintos oficios se La televisión ha tenido una importancia innegable en los años 90 en España, sobre todo para los niños y jóvenes que pertenecen a la llamada generación “Y” o “Millennials”. Este grupo ha crecido paralelamente a la tecnología doméstica y las redes sociales, haciendo de los entornos audiovisuales su hábitat natural. En este contexto, las series televisivas de animación de dicha época causaron una gran influencia en este colectivo que estaba entonces en pleno crecimiento y formación. Nuestro estudio pretende analizar las características sonoras de las cabeceras de las 20 series de animación infantil más vistas en las televisiones españolas de ámbito estatal en los años 90, mediante la aplicación de una plantilla de análisis sonoro-musical validada y aplicada en investigaciones anteriores por diversos autores. Con todo ello se caracteriza el paisaje sonoro que acompañó a esta generación en su infancia, distinguiendo entre distintos perfiles sonoros. Para ello, se analiza la presencia o ausencia de determinados elementos sonoros y musicales, originales o manipulados mediante técnicas de postproducción, orientados a distintos públicos según el sexo, la edad, las emociones, la motivación por la tecnología o por las relaciones sociales. Así pues, se plantea profundizar y sustentar la heterogeneidad presente en los individuos de esta generación, huyendo de clichés homogeneizadores, posibilitando modos distintos de acercamiento a su identidad social y a la riqueza que estos representan para la sociedad española actual, partiendo del sonido que les acompañó y marcó en su infancia.

PALABRAS CLAVE: banda sonora, series de animación, millennials, música, sonido, televisión infantil, identidad

RESUME

Desde o princípio do cinema, nos que somente uma pessoa se ocupava praticamente de tudo, a organização da criação de um filme foi evolucionando, e as diversas funções do processo foram aumentando e especializando-se progressivamente. A noção de autoria coletiva é um conceito difícil de abordar e de compreender em toda sua dimensão. Neste artigo pretende-se analisá-lo, depois de estudar de que modo a estrutura de colaboração em equipe daquela época influía nos seus criadores, e por qual razão que uns são autores, enquanto a outros são negados essa condição. Para examinar a fundo qual era o sistema de trabalho real dos distintos ofícios, se a televisão teve uma importância inegável nos anos 90 na Espanha, sobretudo para as crianças e jovens que pertencem a chamada “Geração Y” ou “Millennials”. Este grupo cresceu paralelamente à tecnologia doméstica e as redes sociais fazendo dos entornos audiovisuais seu habitat natural. Neste contexto, as séries televisivas de animação desta época causaram uma grande influência neste coletivo que estava em pleno crescimento e formação. Nosso estudo pretende analisar as características sonoras das introduções das 20 series de animação infantil mais vistas nas televisões espanholas de âmbito estatal nos anos 90, mediante a aplicação de uma planilha de analises sonoro-musical validada e aplicada em investigações anteriores por diversos autores. Com todo isso se caracteriza a paisagem sonora que acompanhou a esta geração em sua infância, distinguindo entre distinto perfis sonoros. Para isso, se analisa a presença ou ausência de determinados elementos sonoros e musicais, originais ou manipulados mediante técnicas de pós-produção, orientados a distintos públicos segundo o sexo, a idade, as emoções, a motivação pela tecnologia ou pelas relações sociais. Assim, se propõe aprofundar e sustentar a heterogeneidade presente nos indivíduos desta geração, fugindo de clichês homogeneizadores, possibilitando modos distintos de aproximação a sua identidade social e a riqueza que isso representa para a sociedade espanhola atual, partindo do som que os acompanhou e marcou em sua infância.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: banda sonora, séries de animação, millennials, música, som, televisão infantil, identidade

Correspondence: Josep Gustems Carnicer: University of Barcelona. Spain.

jgustems@ub.edu

Diego Calderón Garrido: International University of La Rioja. Spain.

diego.calderon@unir.net

Adrien Faure Carvallo: University of Barcelona. Spain.

adrienfaure@ub.edu

Montoya Rubio: University of Barcelona. Spain.

albamontoya@ub.edu

Received: 12/11/2018

Accepted: 28/02/2019

Published: 15/07/2019

How to cite the article: Gustems Carnicer, J.; Calderón Garrido, D.; Faure Carvallo, A., and Montoya Rubio, A. (2019). Soundtrack and identities in the generation “Y”. [Banda sonora e identidades en la generación “Y”]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 49, 159-174. doi: http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.49.159-174

Recovered from http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/564

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Soundtracks in the TV children animation series

The music children listen to in the mass media is the result of a historical process determined by social, cultural, industrial and expressive changes that rushed into the twentieth century. On them rest a good part of the elements of the sound habitat that have accompanied them as a consequence of the consolidation of the new communicative supports that link music with image, narration and movement (Porta, 2014).

TV has a great influence on the musical tastes and ways of listening to children music, especially thanks to the great plasticity and permeability in these ages. As Porta (2007) points out, TV children programming allows access to the sound analysis of contemporary popular culture due to its daily life, its public and continuous nature, testimony of an era and because it creates an opinion about the values of the sound environment.

In this context, the soundtrack considered as a listening space is a mass media at the same time as an industrial, political and institutional creation that uses the language of music adapted to the audiovisual, using communication and publicity strategies subject to audiences and programming (Porta, 2014). Among its aesthetic uses, its location and temporal space atmosphere stands out (Cuellar, 1997) and its purpose, whether expressive or emotional (Baetens, 2012).

One of the elements to consider from the audiovisual education is the sound, a determining expressive element in the television production. The soundtrack as such is composed of music, sound and noise, with which it produces meanings, effects in the sound thought and also in the characteristics of listening (Delalande, 2004).

Television listening refers to a social construction (Adorno, 2004), a collective popular conception, a group experience that involves humanly organized sounds (Blacking, 2006), a demonstration of a dominant culture that eliminates the differentiating features of diversity or maintains only its stereotypes (Porta, 2004).

In the face of the fierce struggle of the large audiovisual corporations for the young audience, new sound spaces based on miscegenation and fusion must be considered, as well as the creation of new forms of cultural consensus. Despite the fact that television children programming tends towards homogenization, creating a single market for sound images (in 1994-1995, 69% of the fiction programming imported by 88 European television stations came from the USA), there is no shortage of initiatives that pose a different future, although difficult to predict, in the current scenario. The degree and type of acculturation will have a direct impact on the way these messages are understood. The assignment of meaning to sound forms is learned, and that is why we can detect differences in their understanding, creation and use. It is in this triple educational, formative and social intervention intention that this paper is framed.

Given the influence of the soundtrack as music of the everyday environment and its relationships with identity, Brown (2008) insists on the need to integrate different research fields, contemplating the production of consumption and culture, expressing the need to integrate this popular music in the design of research.

1.2. Television and Millennials

Television has had an undeniable importance in the “Y” generation, or “Millennials”. This group has grown in parallel with domestic technology and social networks, making audiovisual environments their natural habitat. In this context, the television series of animation of that time had a great influence on a group that was then in full growth and formation.

The enormous population size represented by the Millennial generation (some 8 million young people, according to Alonso, Gonzálvez and Muñoz, 2016) has generated a great fascination in the business, academic and advertising fields, given that in 2025 it will represent 75% of the global labor force and, in turn, the main consumer segment (Bolton et al., 2013). In order to communicate effectively with the Millennials through Social Networks, one must know their behaviors and motivations well (Ruiz Cartagena, 2017).

The Millennial Generation or Generation Y is defined by the majority of researchers as composed of those born from 1981 to 2000. The denominations of the Millennial Generation are varied: Generation Y, iPod Generation, Global Generation or digital natives, because it is the first generation that has spent its entire life in a digital environment, conditioning its values, work and the way of relating to the world that tends to instantaneous communication (Wesner and Miller, 2008). Its ability to carry out several simultaneous tasks on different platforms is another feature (Prensky, 2001).

In addition to this technological and modern vision, there is a broad consensus on the general features that define Generation Y, and on their differences in values ??with respect to previous generations (Hyllegard, Yan, Ogle and Attmann, 2011): tolerant, optimistic, restless, environmentally committed, daring and rebellious, participatory, teamwork-oriented people who seek a balance between work and leisure that empowers their lives. Burstein (2013) highlights the environment of economic crisis in which they grew, which has conditioned many of their behaviors; a profile prone to activism and protest, with capacity for entrepreneurship, but which also delays emancipation, marriage or the purchase of their first house. Despite the economic crisis, millennials have grown up in a culture of consumption, materialism, in an environment of certain prosperity.

However, these digital environments also pose certain deficits, such as being less skilled in face-to-face communication or when interpreting non-verbal language in a conversation (Hershatter and Epstein, 2010). They are also a generation more ambitious, assertive and narcissistic than the previous ones (Twenge, 2009), demanding instant gratification, overestimating enjoyment, aspiring to work in more creative industries and less conditioned by social and labor structures, considering corporations to be manipulative and aggressive in their communication strategies (Ruiz Cartagena, 2017). They have even come to be labeled lazy, although nonconformist, in short, the antagonists of a fiction story... (Márquez-Domínguez, Ramos-Gil and Moreno-Gudiño, 2018).

The messages intended for Millennials should point out the values and aspirations of that generation, such as authenticity, sincerity, and responsibility for social change. In this sense, videos are 12 times more effective than other media to reach this audience, especially if they avoid rhetorical and institutional language and are fostered by “word of mouth” (Ruiz Cartagena, 2017). The use of an action-oriented language, with active and creative treatment, and using all types of communicative and informative technologies will ensure effective communication with millennials (García-Leguizamón, 2010).

Despite all these shared characteristics, Bolton et al. (2013) consider that stereotyping this generation does not favor the understanding of their needs, since there is also a lot of heterogeneity within Generation Y. That is why it would be interesting to distinguish different profiles among its components and in this sense, the identification with the different soundtracks could be helpful to find different sound and in turn, social profiles. The theory of social identity (Tajfel, 1978) raises a public construction of our identity: individuals behave more favorably towards those we perceive that share our same musical tastes, a favoritism motivated by the need to increase our self-esteem. Musical preferences act as a criterion to be accepted in a group, functioning as an “emblem” that makes it possible to differentiate those who belong to the group from those who do not. One of the paradigmatic moments of the preeminence of musical tastes in the construction of social identity is to be found in adolescence. At this stage, the coincidence in musical preferences is related to the formation of friendships (1.9 times more frequent), a fact that, if it also coincides with a high level of education, is up to 3 times more (Selfhout, Branje, Bogt and Meeus, 2009). Sharing musical preferences entails similarities in social attraction, orientation in values and personality (Boer et al., 2011).

There is no doubt that Millennials have their musical preferences like any other group, although it is likely that we can find different groups within them according to their musical preferences. The TV series that accompanied them in their childhood and youth probably contributed to certain social identification and differentiation.

2. OBJECTIVES

Our study aims to analyze the sound characteristics of the headers of the 20 series of children animation most seen on Spanish television at the state level in the 1990s, through the application of a sound-music analysis template. With all this, we seek to characterize the soundscapes that accompanied this generation in their childhood, distinguishing between different sound profiles within the group.

3.METHODOLOGY

Our study is based on the interpretative paradigm even though it uses quantitative data for its analysis, through the application of a sound-musical analysis template validated and applied in previous research by different authors. With all this, we seek to characterize a soundscape that accompanied this generation in their childhood, distinguishing between different sound profiles. To do this, the presence or absence of certain sound and musical elements, original or manipulated by postproduction techniques, aimed at different audiences according to sex, age, emotions, motivation for technology or social relationships are analyzed.

3.1. Sample

Faced with the impossibility of having the official data provided by public auditing agencies, we have chosen to rely on the list offered by https://www.bekia.es/television/noticias/veinte-series-infantiles-marcaron-ninos-noventa and have analyzed the headers of the 20 TV children series more seen in Spain, based on their Spanish versions obtained in Youtube or Audición: https://listas.20minutos.es/lista/dibujos-animados-y-series-infantiles-recuerda-su-cabecera-130512/

The animation series selected for this paper and most seen in Spain in the 1990s would be:

3.2. Instruments and Data Analysis

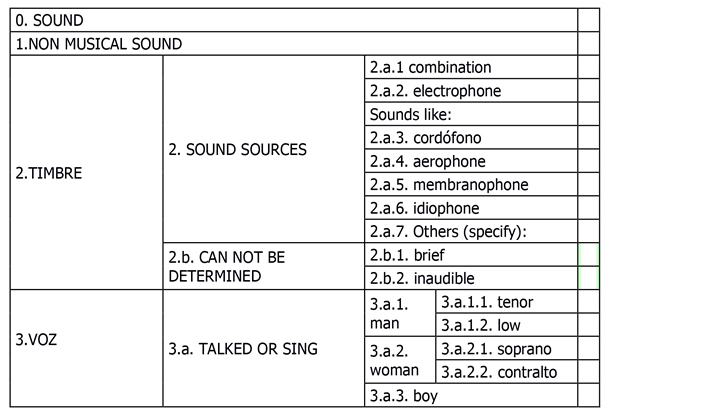

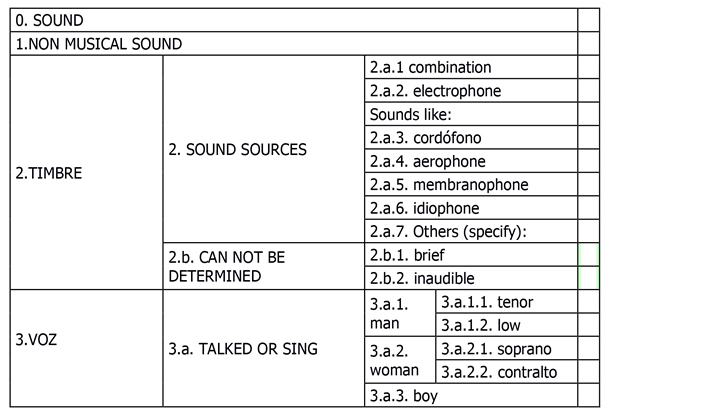

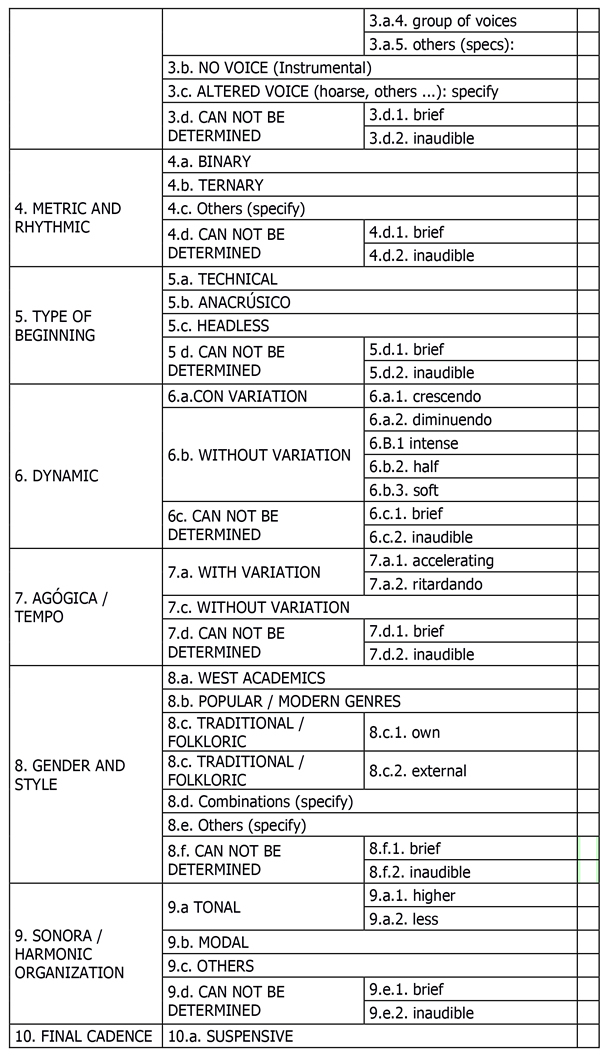

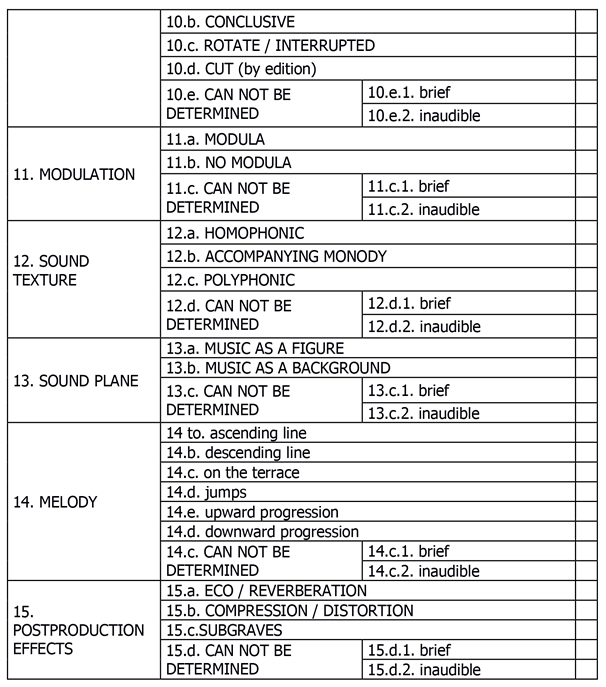

Each of these headers has been applied an analysis sheet designed out of modifications (marked in yellow) to that of Porta and Ferrández (2009) shown below (see Table 1). The template integrates musicological, psychological, sociological, semiotic and music theory criteria. The results have been collected and corroborated by the research team and analyzed later using Excel I SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 21) to calculate percentages, means and correlations.

Table 1: Sound analysis template applied.

Source: Own elaboration.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Regarding the TV series analyzed in this paper, we can affirm that they are foreign, especially of Anglo-Saxon origin, which raises an internationalizing and homogenizing orientation. However, a certain intention is maintained in presenting certain regional or cultural stereotypes reinforced by the image and above all by musical stereotypes (timbral, melodic, rhythmic and harmonic).

The analysis of the headers of the 20 children animation series showed, first of all, that they all used music. In this sense, 15 of the headers presented music as a figure, this being a main element. In the series, in addition, 11 of them were characterized by the use of non-musical sounds, either visual elements that interact with the music itself, such as the horn of Homer Simpson’s car or the ball bouncing on the ground while the protagonists of La Banda del Patio played.

Regarding the sound source, in all cases it was a combination of timbres either produced by acoustic instruments or by synthesizers and electro-phonic instruments. Four of the headers were totally instrumental. In its great majority (16 cases) the presence of male voices prevailed in the tenor tessitura. Said voice sounded alone in 3 series, and accompanied by other voices in other 6 series. The children’s voices were only heard in 3 of the series and always accompanied by a tenor. In the case of female voices, they always appeared in a soprano tessitura and always accompanied by male voices.

Regarding the metric, in all cases it was music in binary or quaternary compass. As far as the rhythmic beginnings were concerned, it was mostly the case of theistic music (in 13 headers), in 6 cases it was an anacrusis and in a single series (Rugrats) it was acephalous. In the case of dynamics, the great majority (16) did not have any variations in their volume, it being medium (9 cases) or intense (7). Regarding the agogic, in all cases the tempo was maintained without any variations. Said tempo was slow in the case of the Gargoyles series, mean in 8 of the headers and fast in the rest (11 series).

As far as the musical genre was concerned, the majority (15 series) had music belonging to popular / modern genres. The rest (5 series) are based on western academic music. The null use of folk music stands out. Regarding texture, accompanied melody (11 headers) predominated as compared to the 9 that had an eminently polyphonic character.

Regarding the sound/harmonic arrangement, the majority of the headers (12) used major modes, while in 6 cases the key tone predominated and, in only two cases (Dragon Ball and The Simpsons) the modal music. As regards modulations, the distribution of the series was exactly the same between those that modulated and those that did not (10 series). In the case of the final cadence, the majority (17) had a conclusive cadence while only one, Dinosaurs, was based on a suspension cadence. In the series Calimero and Las tres mellizas, this cadence could not be heard since it was cut by editing.

If we focus on the melody, most of the series (13 headers) were designed in melodic jumps, while 6 had an eminently ascending progression and a single series (Digimon) in a terrace format.

Finally, and as regards the effects of postproduction, the vast majority (16 cases) had reverberation; Regarding the use of compression, this was evident in 13 of the cases; the use of subbass was only seen in 2 headers and various sound filters in other 2.

According to the calculations made by the SPSS, no internal relationships (correlations) were found among the different parameters, so that some did not interfere or influence others.

In general, the sound of the animation series coincides with the description of Porta (2004 and 2011), Ocaña and Reyes (2010) and the analysis of Gustems and González (2012) regarding the use of off-performed songs, use of occasional noises, use of synthetic-electronic orchestra, sung voices, rock timbre, electronic sounds imitating everyday objects that emit digital sounds, percussion instruments (especially xylophone), binary or quaternary metrics, fast tempo without any variations, the major mode with some modulations, the final cadences, the accompanying melody, and music as a figure. Regarding the work of Gustems and González (2012), despite their multiple coincidences, they differ in the absolute absence of folkloric elements. Regarding the results of Porta (2011), despite the multiple coincidences, it differs from the use of groups of polyphonic voices, the use of melodies with anacrusic beginning and the use of music from other cultures.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Therefore, we can conclude that there is a generalized (75%) prototypical profile of the music for the headers of the series, which we can characterize as: containing music, used in a “figure” way, with some extramusical sounds, use of musical ensembles and of tenor voices, in binary or quaternary rhythm, of thetic beginning, with medium intensity and without changes, with fast tempo and without any variations, of modern-popular style, with predominance of accompanied melody, in a greater mode whether or not modulating, with melodies with jumps, and a suspension cadence. Regarding sound postproduction, the use of reverberation and compression stands out.

This result allows us to raise a profile of a majority millennial public focused on technology, sports and physical activity, social groups, positive emotions (enthusiasm) and male characters. This profile would be greatly influenced by an international view with a clear pre-eminence of American cinema although with a significant presence of the Japanese anime (5 of the series).

In addition to this profile, the remaining 25% would be formed by other profiles with different sensitivity, which we can relate to some of the audio characteristics of the headers. In particular, we will highlight three profiles that deviate from the previous characteristics:

Acoustic, non-technological orientation: characterized by the use of Western academic music, or avoiding distortions in sound postproduction. It would be the case of Laboratorio de Dexter, La banda del patio, Gargoyles, Las tres mellizas, Rugrats and The Simpson.

Introspective orientation, towards the deep emotions: by the use of minor mode and slow tempo. It would be the case of Gargoyles, Inspector Gadget, Pepper

Orientation towards the early ages: by the presence of feminine and infantile voices. It would be the case of: Las tres mellizas, Inspector Gadget, Pepper Ann, Calimero and Los Fruitis.

In the sample we studied, music from other places and never from one’s own culture or tradition is always heard. Television children programming requires proximity content (De Moragas, 1991), however, what is offered is a multicultural space that has lost its own roots to fill it only with the foreign. From an educational perspective, this option somehow questions the identity elements of a social nature, because music speaks of oneself, of the others and with the others. Valuing the diversity supposes the re - knowledge of what is proper at an early age, because this egocentric speech will give rise, in its journey, to internal speech, and music is on the way (Porta, 2004).

In this text we have shown some aspects scarcely analyzed in the musical studies of television and its influence on children, but which emerge when studied from semiotics, formal analysis and cognitive theories. Porta (2011) comments on how the film and television soundtrack has an educational influence and a social responsibility as part of the construction of the child’s consciousness, because they contribute to their cognitive, social, expressive, aesthetic dimension and in a critical future. Ocaña and Reyes (2010) emphasize the power of TV in the anchorage and sound influence of generations that have been much accompanied by TV during their childhood. The little musical interaction exerted by the families where these millennials have grown does not allow us to think of any other type of filter, beyond the fashions of each moment.

Despite the lack of interactivity with TV, the great success that these series had in the context of the childhood and youth of the millennials in Spain enables knowledge of the typologies of their soundscapes through the headers of the series: With all this, it is proposed to sustain the heterogeneity present in the individuals of this generation, fleeing from a single homogenizing cliché, enabling different ways of approaching their social identity and the richness they represent for the current Spanish society, based on the sound that accompanied and marked them in their childhood.

REFERENCES

1. Adorno TW (2004). Filosofía de la nueva música. Madrid: Akal.

2. Alonso MH, Gonzálvez JE, Muñoz AB (2016). Ventajas e inconvenientes del uso de dispositivos electrónicos en el aula: percepción de los estudiantes de grados de comunicación. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 41, 136-154.

3. Baetens J (2012). Beyond the Soundtrack: Representing Music in Cinema. Leonardo, 41(4), 406-407. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/leon.2008.41.4.406

4. Blacking J (2006) ¿Hay música en el hombre? Madrid: Alianza.

5. Boer D, Ficher R, Strack M, Bond MH, Lo E, Lam J (2011). How shared preferences in music create bonds between people: values as the missing link. Personality and Social Bulletin, 37(9), 1159-1171. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167211407521

6. Bolton RN, Parasuraman A, Hoefnagels A, Migchels N, Kabadayi S, Gruber T, Solnet D (2013). Understanding generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda. Journal of Service Management, 24(3), pp. 245-267. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09564231311326987

7. Brown AR (2008). Popular Music Cultures, Media and Youth Consumption: Towards an Integration of Structure, Culture and Agency. Sociology Compass, 2(2), 388-408. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00103.x

8. Burstein D (2013). Fast Future: How the Milenial Generation is Shaping Our World. Boston: Beacon Press.

9. Cuellar C (1998). Cine y música: el arte al servicio del arte. Valencia: Publicaciones de la UPV.

10. Delalande, F. (2004). La enseñanza de la música en la era de las nuevas tecnologías. Comunicar, 23, 20-24.

11. De-Moragas M (1991). Teorías de la comunicación. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

12. García-Leguizamón F (2010). Educación en medios ayer y hoy: tópicos, enfoques y horizontes. Magis. Revista Internacional de Investigación en Educación, 2(4), 279-298. Disponible en https://goo.gl/QZLR7B

13. Gustems J, González O (2012). La Música en la programació infantil de la Televisió pública de Catalunya. Prodiemus, 2012, 10-23.

14. Hershatter A, Epstein M (2010). Millenials and the world of work: an organization and management perspective. Journal of Business Psychology, 25 (2), 211-223. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9160-y

15. Hyllegard K, Yan R, Ogle J, Attmann J (2011). The influence of gender, social cause, charitable support, and message appeal on Gen Y’s responses to cause-related marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(1-2), 100-123.

16. Márquez-Domínguez C, Ramos-Gil YT, Moreno-Gudiño BP (2018). La generación millennial se identifica con “la pera del olmo”. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 9(2), 159-172.

17. Ocaña A, Reyes ML (2010). El imaginario sonoro de la población infantil andaluza: análisis musical de “la Banda”. Comunicar, 35(XVIII), 193-200.

18. Porta A (2004). Contenidos musicales buscan currículum. Comunicación y Pedagogía: Nuevas tecnologías y recursos didácticos, 197, 31-36.

19. Porta A (2007). Músicas públicas, escuchas privadas. Barcelona: Publicacions de la UAB.

20. Porta A (2011). La oferta musical de la programación infantil de «TVE» como universo audible. Comunicar, 37(XIX), 177-185.

21. Porta A (2014). Explorando los efectos de la música del cine en la infancia.

22. Arte, Individuo y Sociedad, 26(1), 83-99. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/rev_ARIS.2014.v26.n1.40384

23. Porta A, Ferrández R (2009). Elaboración de un instrumento para conocer las características de la banda sonora de la programación infantil de televisión. Relieve, 15, 2.

24. Prensky M (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816

25. Ruiz-Cartagena JJ (2017). Millennials y redes sociales: estrategias para una comunicación de marca efectiva. Miguel Hernández Communication Journal, 8, 347-367.

26. Selfhout MHW, Branje SJT, Ter-Bogt TFM, Meeus WHJ (2009). The role of music preferences in early adolescents’ friendship formation and stability. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 95-107. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.11.004

27. Tajfel H (1978). Differentiation between social groups. Londres: Academic Press.

28. Twenge JM (2009). Generational changes and their impact in the classroom: Teaching generation me. Medical Education, 43(5), 398-405. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03310.x

29. Wesner MS, Miller T (2008). Boomers and Millenials have much in common. Organizational Development, 26(3), 89-96.

AUTHORS

Josep Gustems Carnicer: PhD in pedagogy, Higher degree in music, Full professor of didactics of musical expression (UB), with 200 publications on sound and education.

jgustems@ub.edu

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6442-9805

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=eWy2oOAAAAAJ&hl=ca&oi=ao

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Josep_Gustems

Diego Calderón Garrido: Degree in Music, Doctor of Art History. Professor Contracted Doctor in the UNIR, with 50 articles on the sound fact.

diego.calderon@unir.net

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2860-6747

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=0kZGZ48AAAAJ&hl=ca; ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Diego_Calderon-Garrido;

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57192679954

Adrien Faure Carvallo: Graduated in Musicology by the UAB, master’s degree in Secondary Teacher Training (UB). Associate professor (UB).

adrienfaure@ub.edu

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6065-5186

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=list_works&hl=es&authuser=2&user=ldeepkMAAAAJ

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Adrien_Faure3; https://independent.academia.edu/AdrienFaure

Alba Montoya Rubio: PhD in History and Theory of Arts (UB), Bachelor of Audiovisual Communication (UPF), Master “Music as interdisciplinary art” (UB-URV-ESMUC), associate professor (UB).

albamontoya@ub.edu

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9337-7266

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=kGjUt-cAAAAJ

Academia.edu: https://ub.academia.edu/AlbaMontoya

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alba_Montoya_Rubio