doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.48.17-43

RESEARCH

THE WORLDVIEW OF THE SPANISH TRANSITION IN THE MOVIE JOAN THE MAD... ONCE IN A WHILE A MANUAL FOR THE UNDERSTANDING OF THE HISTORICAL COMEDY OF THE EIGHTIES

LA COSMOVISIÓN DE LA TRANSICIÓN ESPAÑOLA EN LA PELÍCULA JUANA LA LOCA… DE VEZ EN CUANDO UN MANUAL PARA LA COMPRENSIÓN DE LA COMEDIA HISTÓRICA DE LOS OCHENTA

A COSMOVISÃO DA TRANSIÇÃO ESPANHOLA NO FILME JUANA LA LOCA.... DE VEZ EN CUANDO UM MANUAL PARA A COMPREENSÃO DA COMÉDIA HISTÓRICA DOS ANOS 80

Antonio Rafael Fernández Paradas1, Rubén Sánchez Guzmán2

1University of Granada. Spain.

2City Council of Madrid. Spain.

Research carried out within the Educational Innovation Project of the University of Malaga “Implementation of improvements in the teaching-learning digital skills in the Humanities, Social Sciences and Education” PIE 17-020.

ABSTRACT

Although it was one of the great movie blockbusters of the time, Joan the Mad... once in a while (José Ramón Larraz, 1983), received harsh criticism from the specialized public, who saw in the film a painful way of making movies. Characters, ambience, script, interpretations, etc., nothing escaped the pen of the critics, who vented their criticism on it. Even so, the public connected perfectly with it, not in vain, the Court of the Catholic Kings came to make the distant Spanish transition their own. Through the following research, we want to value this important contribution of Spanish cinema, as a document that perfectly reflects the political, social, cultural and artistic life of the Spanish Transition, offering a compendium that allows us to understand the thoroughness and intellectuality of the script in all its complexity.

KEY WORDS: Spanish Transition, Joan the Mad... once in a while, historical comedy, cinema, Catholic Kings, José Ramón Larraz, Parody.

RESUMEN

Aunque fue uno de los grandes taquillazos cinematográficos de la época, Juana la Loca… de vez en cuando (José Ramón Larraz, 1983), recibió unas duras críticas por parte del público especializado, que veían en la cinta una penosa manera de hacer cine. Personajes, ambientación, guion, interpretaciones, etc., nada escapó a la pluma de los críticos, que se cebaron duramente con ella. Aun así, el público conectó a la perfección con ella, no en vano, la Corte de los Reyes Católicos vino a hacer suya la lejana Transición española. Mediante la siguiente investigación, queremos poner en valor esta importante aportación del cine español, como un documento que refleja a la perfección la vida política, social, cultural y artística de la Transición española, ofreciendo un compendio que permita comprender la minuciosidad e intelectualidad del guion en toda su complejidad.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Transición española, Juana la Loca… de vez en cuando, comedia histórica, cine, Reyes Católicos, José Ramón Larraz ,Parodia.

RESUME

Embora tenha sido um dos grandes êxitos cinematográficos da época, “Juana la Loca... de vez em quando” (Jose Ramon Larraz, 1983), recebeu duras críticas por parte do público especializado que viam no filme uma penosa maneira de fazer cinema. Personagens, ambientação, guião, interpretações, etc, nada escapou dos críticos, que se excederam duramente com ela. Ainda assim, o público conectou a perfeição com ela, devido a parodia feita em referência à a Transição Espanhola trasladada à corte dos Reis Católicos. Mediante a seguinte investigação, queremos ressaltar esta importante aportaçao do cinema espanhol, como um documento que reflete à perfeição a vida política, social, cultural e artística da Transição Espanhola, oferecendo um compendio que permita compreender a minuciosidade e intelectualidade do guião em toda sua complexidade.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Transição Espanhola, Juana la Loca... de vez em quando, comedia histórica, cinema, Reis Católicos, Jose Ramon Larraz, Parodia.

Correspondence: Antonio Rafael Fernández Paradas: University of Granada. Spain.

antonioparadas@ugr.es

Rubén Sánchez Guzmán: City Council of Madrid. Spain.

ruben_sanguzman@hotmail.com

Received:18/09/2018

Accepted: 21/01/2019

Published:15/03/2019

1. INTRODUCTION

Spain is not a country that has excessively exploited our history in the cinema. During Franco’s period, this genre was often exploited for specific patriotic and propagandistic purposes, the great epic characters of Spanish history began to parade through the neighborhood cinemas, the Catholic kings, Joan the Mad, the Columbian epic, on other occasions they are a simple pretext for a historical melodrama, Where do you go Alfonso XII? With the death of General Franco (Zunzunegui, 2005) and the arrival of the transition, the palette of characters is broadened, the cinema emerges from its previous political connotations, new themes appearing, sometimes more committed (González González, 2009). Singular is the fact of a subgenre that occurs in the early eighties (Torres, 1992), which delves into the major themes of the history of Spain, connected with previous works of Franco’s regime (Alba of America or Love madness) (Del Amo, 2009). The payroll is not broad, just a small handful of films that, although being box-office hits at the time, were crushed by critics (Montoya et al, 2015). The first to be released in 1983 was Christopher Columbus a discoverer by trade that came to make more than a million and a half spectators go to the cinema, it was followed a year later by Joan the Mad… once in a while (a true paradigm of the ephemeral subgenre) and The infuriating Cid (Payán, 2007). All of them, but above all the transcript of Love madness by Juan de Orduña, (Joan the Mad… once in a while) directed by José Ramón Larraz with a screenplay by Juan José Alonso Millán, thanks to its highly contemporary humorous gags, they are a surprising exponent of semantic duality. On the one hand, the historical re-creation of the film, characterization of characters, locations, etc., on the other hand, the gags referring to the Spain of the nineteen eighties. These can be found in different ways both as anachronistic objects, and especially in the dialogues of the script, difficult to understand for those generations who did not live or are familiar with the political, economic or social and cultural life of the transition. In view of the above, it is this duality that makes resources, at the same time, attend to two distinct periods separated by centuries from each other (Martínez Montalbán, 1989), (Monterder, 1993).

2. OBJECTIVES

The main objective of this piece of research is to highlight, with the perspective of the 35 years that have passed since the premiere of Joan the Mad… once in a while, that the harsh criticisms that the film received at the time of its premiere, both in its interpretative apparatus and the script of the film, nowadays take on a totally different dimension. To us, Joan the Mad seems to us like a historical document of the first magnitude, the correct understanding of which is an open book about the ways of life, of feeling and creating in the Spain of the democratic Transition. The contemporary critics to the premiere of the film already emphasized the multiple references to the cultural, political, legislative and domestic life of that Spain that began to move away from the saddened legacy of Franco’s regime. Precisely, criticism, in general, indicated the inappropriateness of building a script based on such references. The opposite effect was the impact that the film provoked at the box office, exponentially surpassing the success of the “cult films” or “well done films” of the time.

It is the circumstance that at present, a Spaniard born after Naranjito (the mascot of the 1982 Soccer World Cup in Spain), and much less one that came into the world after the burial of the peseta (2000), is materially impossible to understand the film Joan the Mad… once in a while, in its total plenitude, since the comments, pranks and parodies reflect a certain worldview of the world, which can hardly be understood by those who did not live it. In the 21st century, it is necessary to go to semiotics (Vidales González, 2009) and iconography to understand the film in its huge intellectual complexity.

Specifically, we want to respond to the following objectives:

Analyze each and every one of the references to the social, cultural, political, economic, domestic, technological life shown in the film.

Identify and interpret these references.

Analyze these references under the audiovisual, communicative, expressive, creative and cultural codes of the time.

Create a corpus of knowledge that allows any person to understand the movie Joan the Mad in a simple, orderly and organized way.

3. METHODOLOGY

From the methodological point of view, four concatenated processes have been carried out. At first, the film has been contextualized in the historiography and the theoretical framework. We wanted to know what has been said about the film and how, among the scientific intelligentsia. In the second place, we have consulted directly, thanks to the archives of the National Film Archive, the criticisms that the film received at the time of its premiere. We have also analyzed various statistical data that have allowed us to understand the economic and social dimension of the film. In a third stage we have fully minuted the film, focusing on the economic, cultural, scientific, social, technological, judicial, legislative, judicial aspects we can find (Losilla Alcalde, 1999) . Here is an appreciation; we had the opportunity to directly consult the original script of the film preserved among the stocks of the National Film Archive. To make the minute of the film and extract the comments subject of analysis, we have done it directly on the tape itself, and not on the script, since we have been able to observe notable differences between the script and the final film. Once we have analyzed the filmic text, we have created a triple entry table, where, in a sequential order, we have literally collected the comment of the film and proceeded to analyze and interpret it under the visual codes of the time. It is important to mention that we have not only included textual citations but have also analyzed decorative and use objects, magazines and newspapers that appear, technological instruments, such as videos, etc. The corpus of generated knowledge has allowed us to expand the knowledge we had about the film Joan the Mad… once in a while, highlighting its importance today as a historical document.

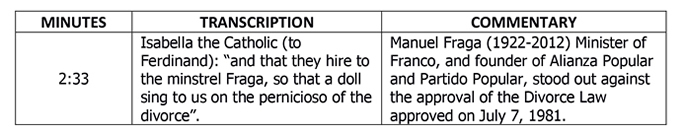

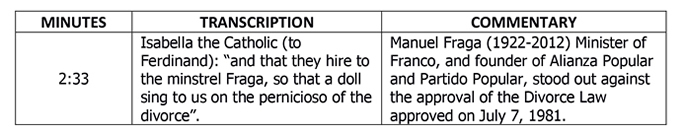

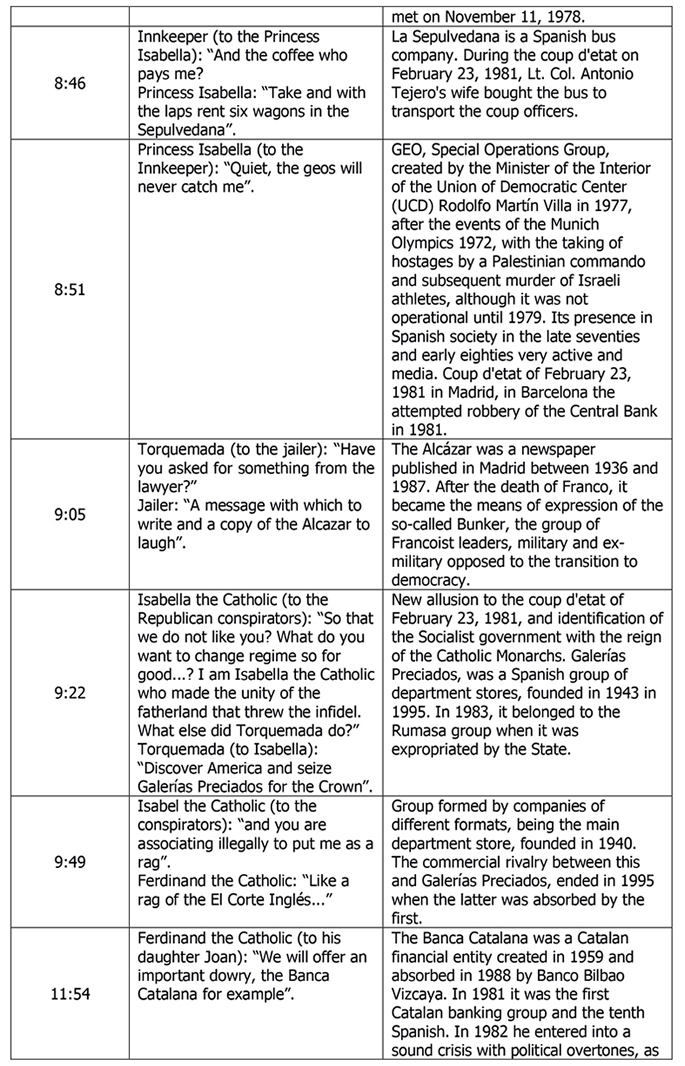

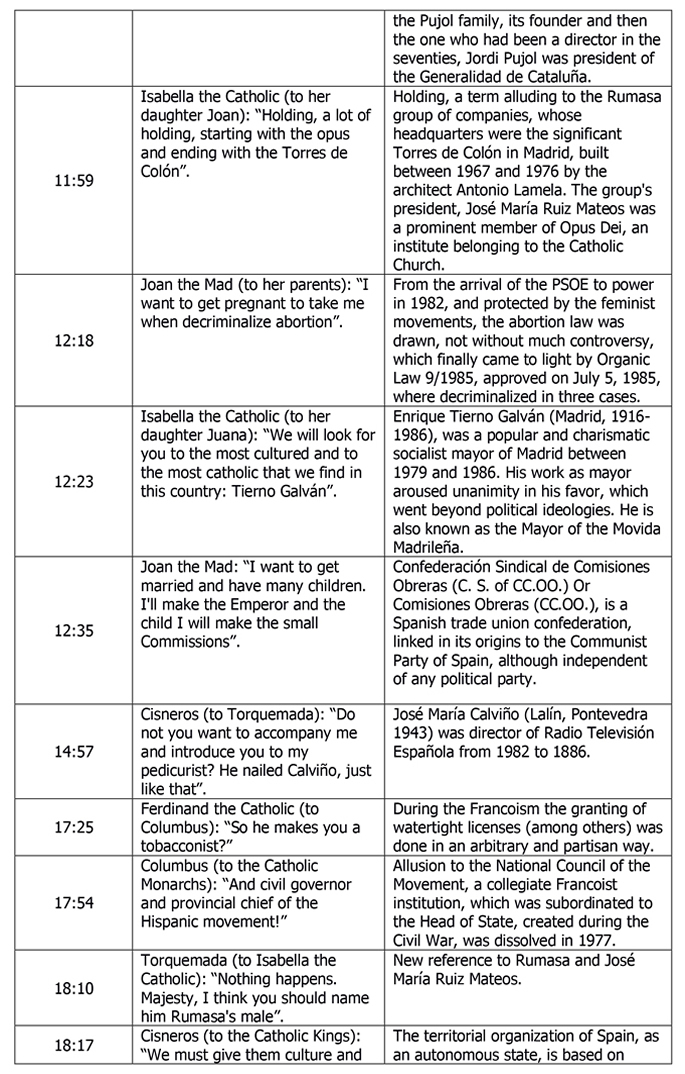

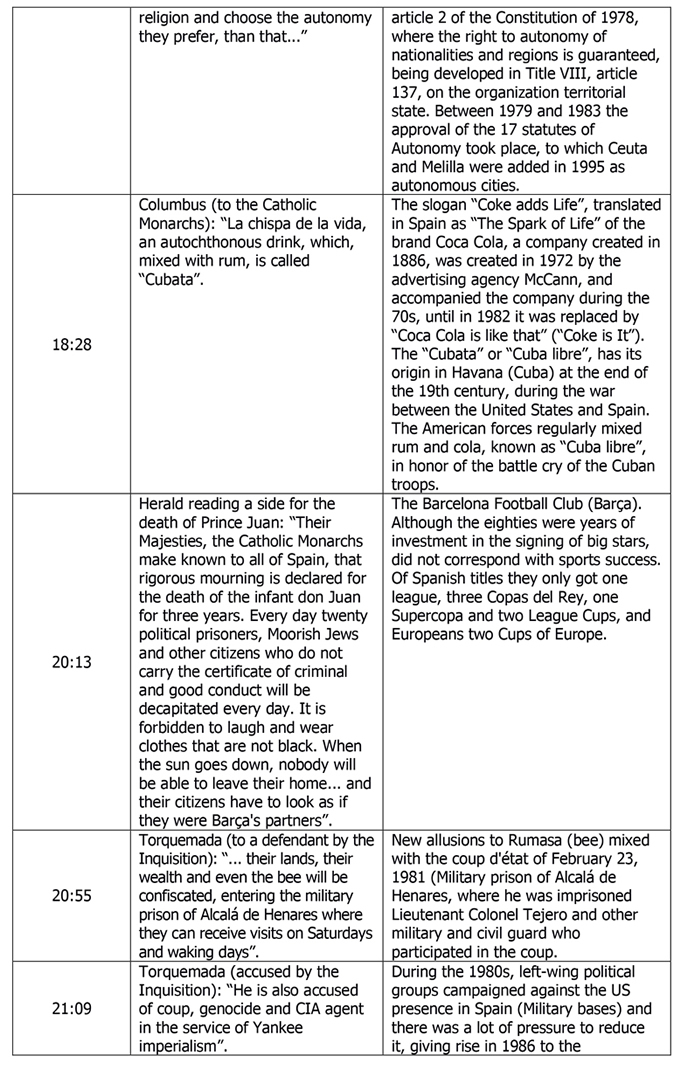

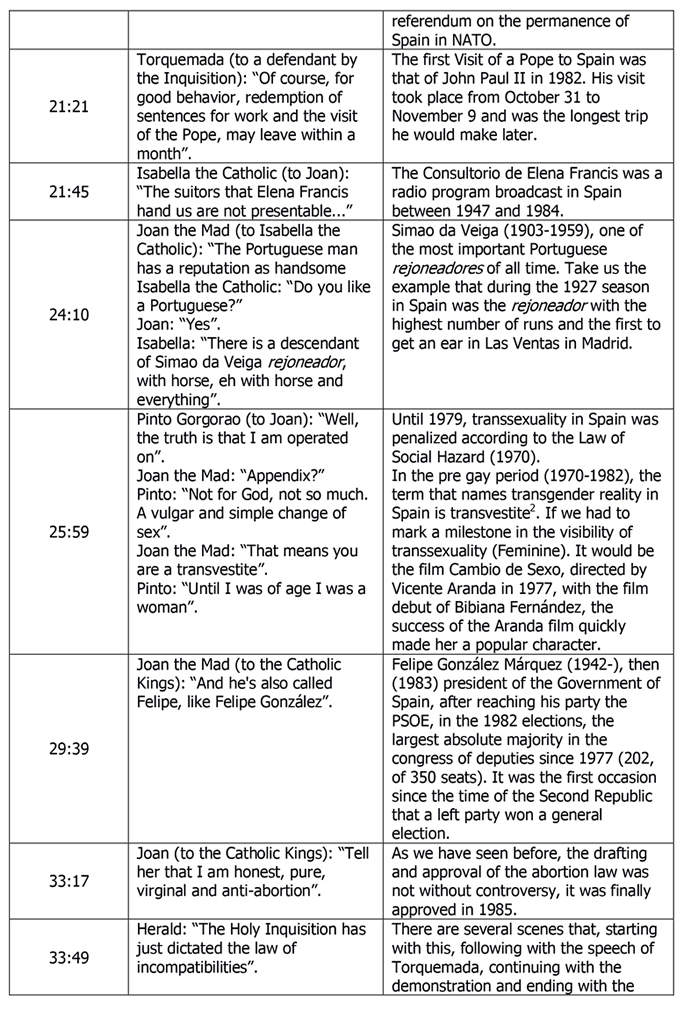

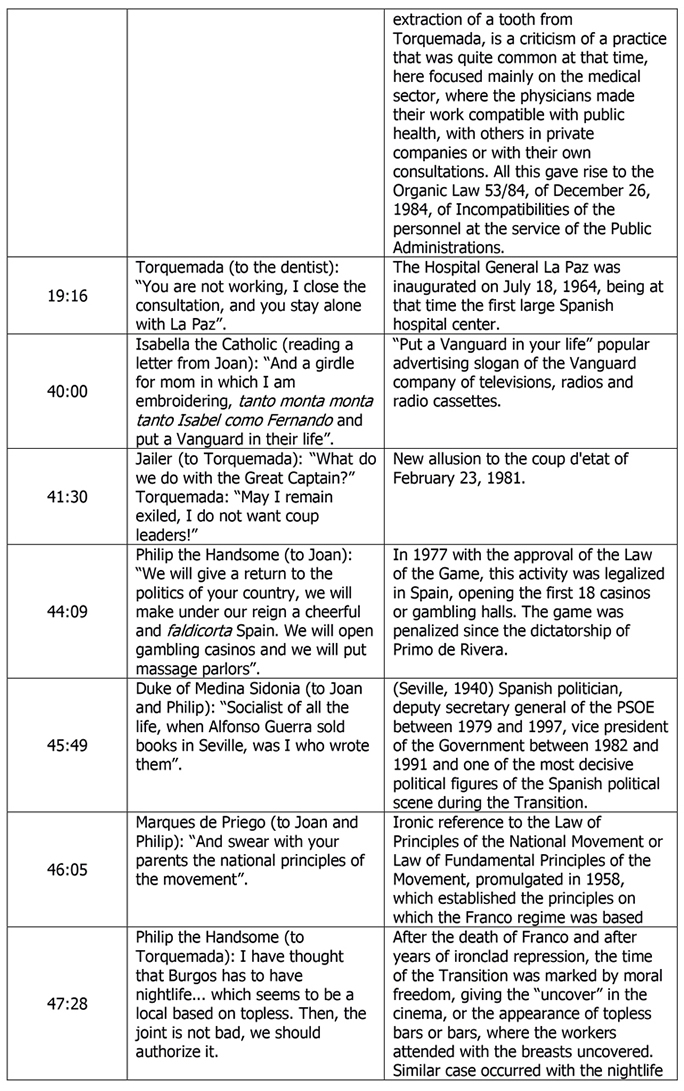

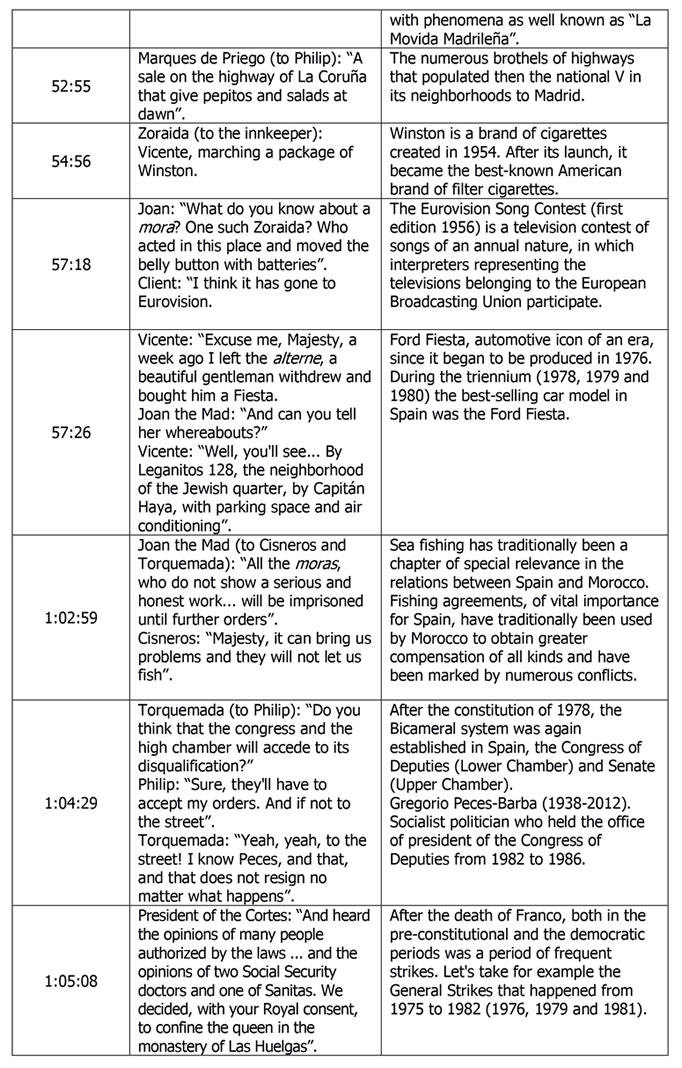

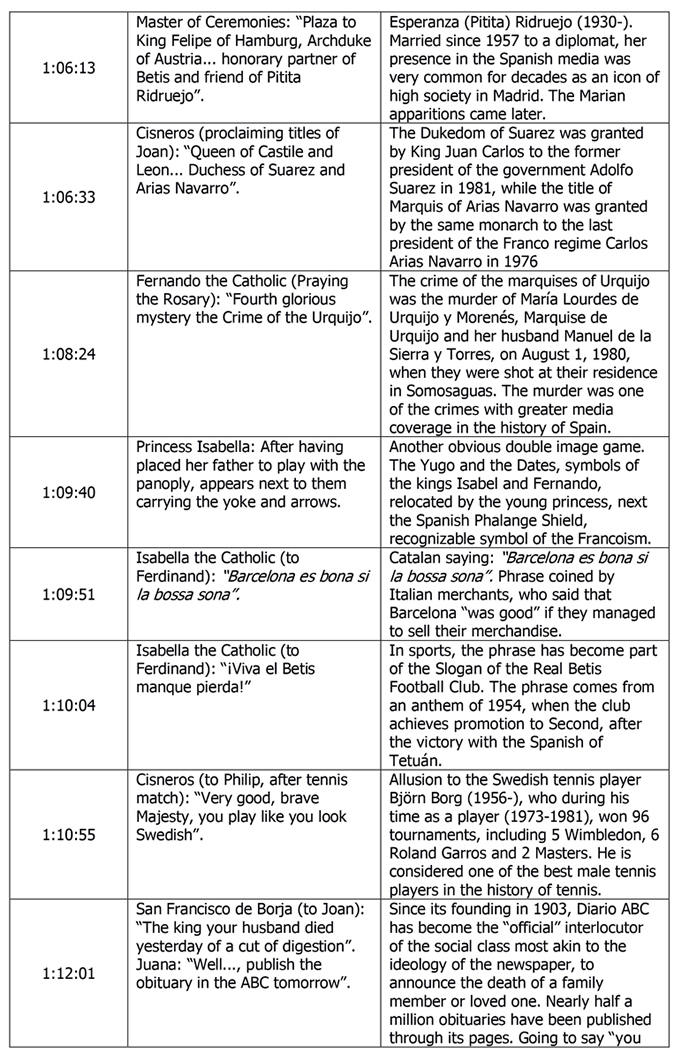

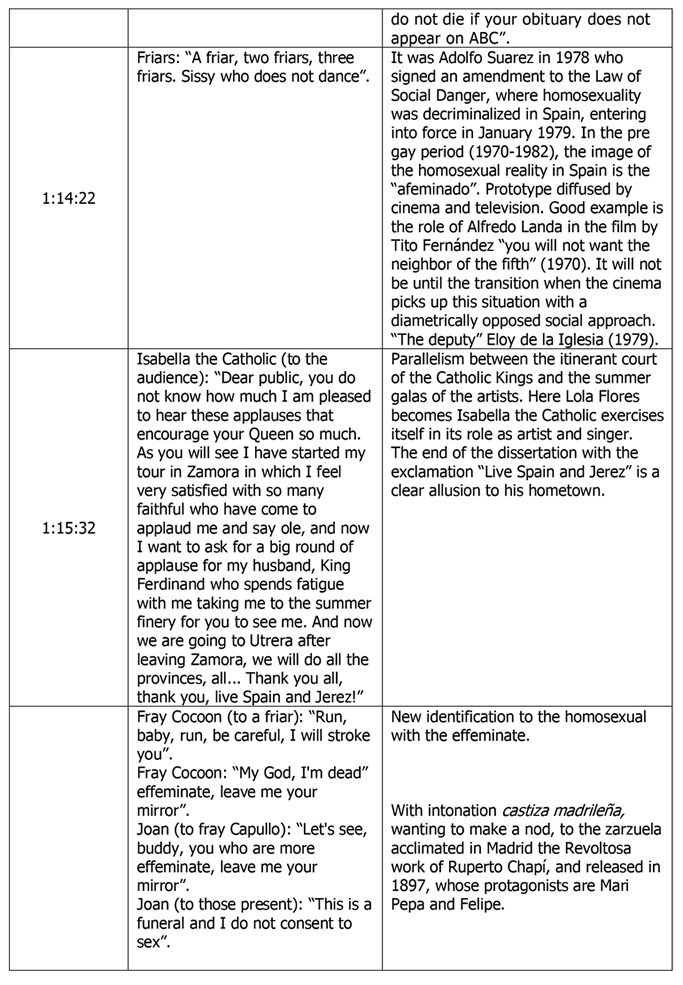

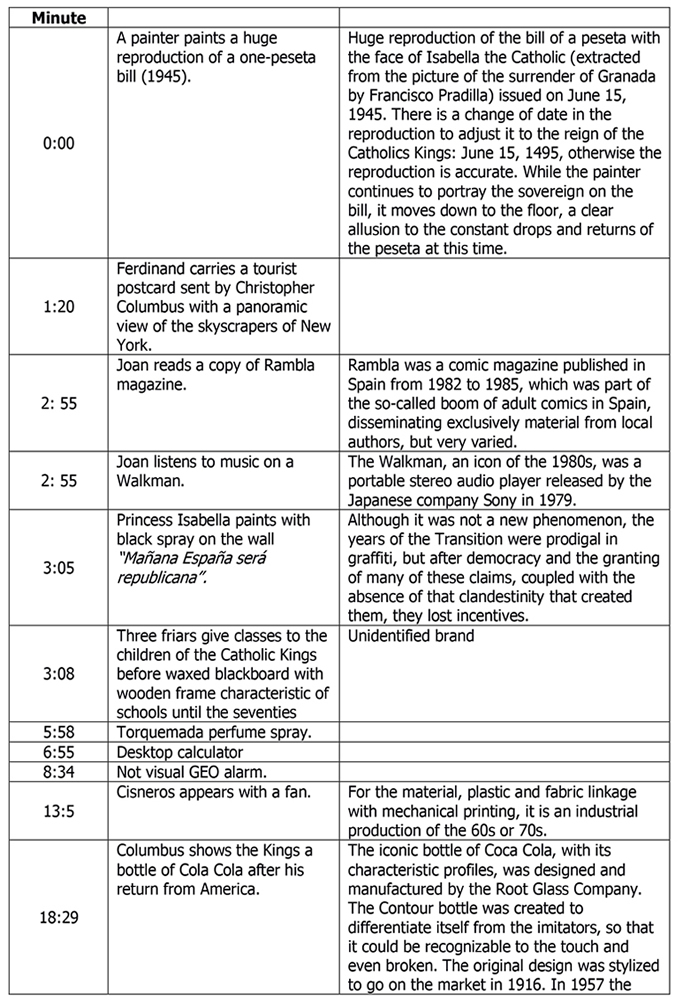

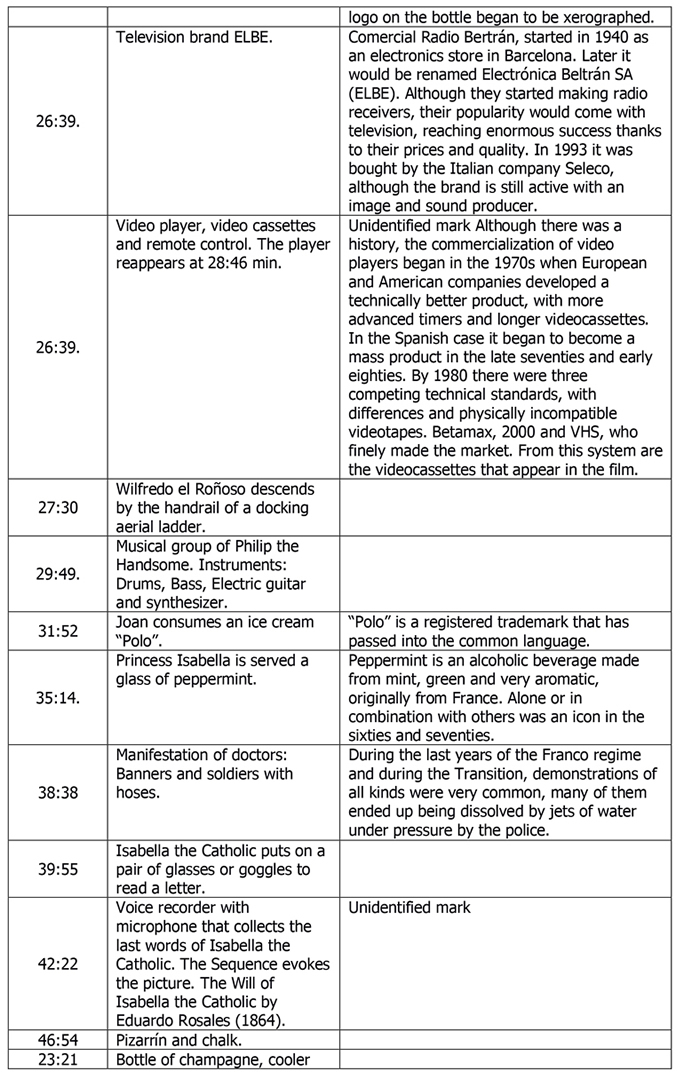

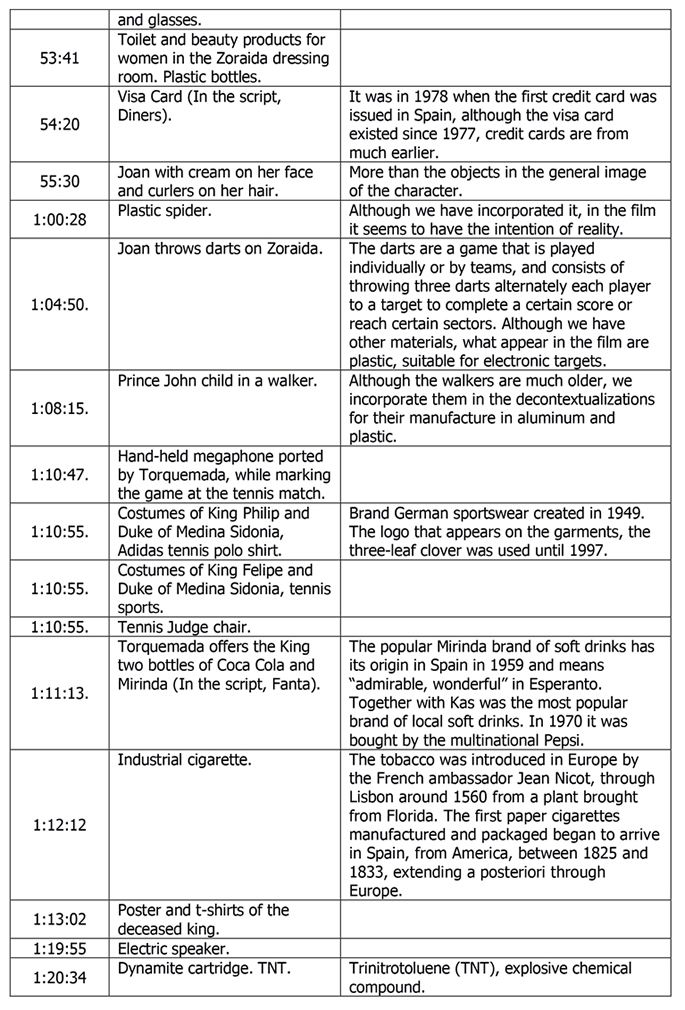

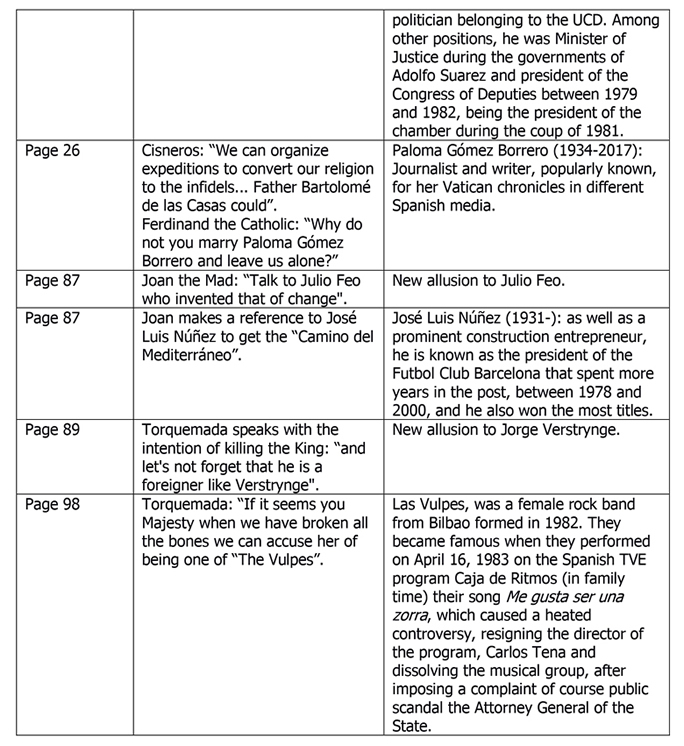

Tabla 0. Example of the table made and the interpretations of the comments and objects.

Source: Own elaboration.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Joan the Mad, reactions to a movie

It can be considered that the pioneer in this genre (a pure ludicrous farce with recognizable historical characters) was Christopher Columbus, a discoverer by trade (1983), produced by José Frade and directed by Mariano Ozores, a tandem that had previously worked together in other comedies The magical league (1980) and Magical witches (1981), following the trail of Magic powders (1979), the first comedy set in a context of terror, which had an extraordinary commercial yield. The bases were already created and it did not take long to catch the totems in the history of Spain encumbered by the Franco-supporting cinema, Alba of America (1951), Love madness (1948), and that its protagonists, with true impudence, talked about the politics of the time, new social changes, or contemporary characters, surrounded by anachronistic objects (Losilla Alcalde, 1999). In addition to Mariano Ozores as director, Frade had Juan José Alonso Millán as screenwriter, a theatrical author who debuted collecting the essences of satirical and absurd humor in the line of Jardiel and Mihura, and the friendly and commercial comedy of Alfonso Paso, and at that time he was one of the most required screenwriters for commercial cinema (humor and nudity) that triumphed in Spain (almost 60 scripts in 20 years), with movies as popular as You shall not covet the neighbor of the fifth floor (1971), (Payán, 2007). Alonso Millán became a true puppeteer who, to move to Columbus, the Catholic Kings, Torquemada or Cisneros in some circumstances and dialogues that demystified them completely, with constant allusions to the Spanish reality of the moment (López Gandía and Pedraza, 1989). The film premiered at Callao movie theater in Madrid on September 8, 1982 (the same year that José Luis Garcí had won the Oscar with Starting again), was as one might expect riddled with Criticism, although it is true that a little disconcerted with this a new formula of making comedy, which had both national and foreign precedents (Muñoz Seca or the Monthy Pytton). However, the film had an unprecedented commercial success, with box office receipts amounting to 1,725,384.69 Euros, and 1,412,893 spectators, becoming the biggest box-office Spanish hit of the year, knocking out The hive of Mario Camus, who a year later got the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. Andres Pajares comments that when he crossed paths with Camilo José Cela, the creator of The hive and winner of the Nobel Prize, he reprimanded him that Christopher Columbus, a discoverer by trade (1982), was knocking out the cinematographic adaptation of his work at the box office. “Surely yours is more fun”, Cela snapped. https://elpais.com/elpais/2018/05/17/icon/1526574743_362895.html (accessed July 1, 2018).

After the success of Christopher Columbus, a discoverer by trade, his producer José Frade wanted to continue exploiting the vein with Joan the Mad… once in a while (1983), which can be considered a continuation of the former, since the film continues where the other leaves it, after the discovery of America by Columbus, the visual aspect is very similar, and many of its characters were endowed with similar characteristics, even (the case of Torquemada, Cisneros and Joan the Crazy) played by the same actors. The choral cast with the most popular actors of the moment (José Luis Vázquez, Lola Flores, Manolo Gómez Bur, Quique Camoiras, Juanito Navarro, Beatriz Elorrieta or Jaime Morey), Frade had, again a script by the aforementioned Juan José Alonso Millán, although in this case with a greater content of the politics of the moment. The tape was commissioned to José Ramón Larraz, who had already directed other scripts by Alonso Millán (The national mummy, 1981). Larraz began his career as a comic writer for magazines, from here he went on to photography and then to cinematography. In 1974 he had his first success, Symptoms, which represented Great Britain at the Cannes Film Festival, and that same year The daughters of Dracula, an icon of Spanish fantasy cinema of the nineteen seventies (Fantaterror), as he converted vampires into beings full of sensuality, mixing terror with eroticism. Back in Spain, in 1976 Larraz would specialize in horror films that he would alternate with the purely erotic ones, with occasional returns to the comedy, whose first incursion was Magic powders in 1979, until 1994 he directed more than 14 films. Retiring definitively in 2002 with the miniseries Village Wind: Miguel Hernández (2002) that tells the life of the poet from Orihuela. Beaten by the Spanish critics since his return (the opposite of how he was treated in England and the United States), as Larraz himself acknowledged, he only received in his career in Spain two good reviews, one by Diego Galán and another by Maruja Torres, and both by The voyeur (1977), considered by him to be one of his best films. Joan the Mad… once in a while was not an exception in the bad reviews, as we will see (García Barrientos, 2004). The film shot during 1983 was released on September 19, 1983 in the movie theaters Roxy (room A), Windsord (Room A) and Montera in Madrid, and a day later in Barcelona in the movie theaters Borras and Rex. The premiere was preceded by an extensive advertising campaign, which announced the film as “A movie that will make you go crazy for a while”, “Mrs. Joan was crazy but not so much”, “After Columbus comes Mrs. Joan, crazy”, “Philip was as beautiful as horteripop”, “The craziest reign of Castile”. While and although the data (viewers and box office receipts) were far from equal to those of Christopher Columbus, it was seconded again by the viewers, with a total of 370,469, and box office receipts amounting to 468,283.76 Euros. As on so many other occasions, the taste of the spectators and the critics were not on the same path, the latter dismembered the film and the script. The critic Raúl Carney in Cine Asesor, the exclusive information page for film exhibition companies, argued that “There is a certain cinema, the common denominator of which is vulgarity and bad taste. This film, in the line of Mariano Ozores, promises to have a fun time, but its script and dialogues are a real shame”. He goes on beating the script “they resort to the now-so-used opportunity to make people laugh on the basis of timelessness, mixing ancient history with social connotations of the Spanish reality of 1983. Rumasa is stupidly quoted as well as politicians and other paraphernalia known to all and being of public domain”. Carney avails himself to refer to the satiety (at least concerning him) of this particular type of comedies “it may be that the public that only wants to have a moment of laughter in the cinema and cares little about the film quality can have fun, but we keep saying that this Spaniard is no longer so stupid and wants worthy products in exchange for his 300 pts”. He ends up admitting that, in spite of everything, this type of cinema has its audience, qualifying it as Medium to Good Performance, recommending its programming in “popular circles and in double programming”.

F. Marinero, in Diario 16 as of September 24, 1983, after being surprised by the success of Christopher Columbus, a discoverer by trade, speaks of the formula of success that is repeated “a parody of time with constant references to the present, the inclusion of musical acts and the multiplication of thanks in charge of a cast of celebrities”. He continues talking about the distribution of the film between two types of jokes, the demystification of the characters “Fernando is a subjugated husband that López Vázquez has represented so much in local-customs-focused comedies. Cisneros is an effeminate mummy and Torquemada a Zascandil puritan”, and the “political joke that is a joke only as regards its limitation to quote public figures or make comparisons with the expropriation of Rumasa”. Finishing the column, not without some irony, “that, plus other samples of ingenuity that range from the use of an electronic calculator to infantile eschatology, makes Joan the Mad… once in a while, not the maddening comedy that it is intended to be but a boring succession of the topics of reactionary humor”.

No less forceful was the criticism of the newspaper ABC as of September 21, 1983. Highlighting the general characteristics of relying “on anachronism and coarse salt”, it continues to attack the director who is qualified as “an English porn specialist”, finishing off that “the assumed vulgarity ends up becoming pure tackiness”, at the same time that it hits the ceiling, let us remember that it is the ABC, with the final cry of “Long Live the Republic”, who qualifies as “inadmissible” as well as “to seem to want to endow the above with a more than glassy political meaning”. Days later, on October 1 the Seville edition of ABC once again spoke its mind freely. Picking up the arguments of the previous column, it added that it was “a ludicrous farce with a coarse humor that borders on vulgar” and concluding that it was “a lute of the celtiberian handlebar”, does anyone give more?

More corrosive, if possible, with obvious political overtones, was the Catalan newspaper AVUI, in its film review of September 25. After making a brief review of the director “for the title, the type of publicity and the name of some interpreters, it seemed that Larraz wanted to give us an entertainment about “adybirds”, transvestites and other singular outcasts”, a real barrage of disqualifications begins, “The collection of nonsense to which the characters dedicate themselves, the irreverence and inconsistency of the thematic treatment, the lack of grace and ingenuity of the allusions to the present... are not at the service... of a demystifying litter or a critical analysis made in jest, but of a simple and insubstantial clown without letting go” although, in the end, it aims to see them “disguised as historical and hysterical figures that Franco’s regime converted into a myth to delirium, has a certain grace”.

Much more benevolent was the criticism by sports newspaper AS on September 24, no doubt alien to any cultural infinity. Praising the excellent cast and predicting a good commercial career, while remarking that, if “the main concern with this film is to make the public laugh, they have achieved it fully”.

But what did the actors of the film think? We have the words of Ferdinand the Catholic, as a sample. In the biography of José Luis López Vázquez, he uses the term “food” (that is, they fed him) to refer to Joan the Mad and other similar products of the time, and continues “Man, you knew what it was... Since, as with Joan the Mad or another one that I also made about Christopher Columbus, they were films that were made conscientiously because one, logically, already knew what one was going to perpetrate... they were bad historical parodies, with coarse humor, but we did it because they paid us... we were willing to finish, one thought, to see when I take this off” (Lorente, 2010, p. 250). The opinion has been clear.

Although, as we have pointed out with figures, the success of Joan was distant from the one attained a year before by Christopher Columbus, it cannot be denied that it was another economic hit, therefore, the formula was exploited until its exhaustion. The same year of 1983, another producer, in this case Ramiro Bermúdez de Castro, went up in the wake with the Mad history of the three musketeers, a movie for the then humorous trio Tuesday and 13, directed by Mariano Ozores, with a script written by Mariano and again Alonso Millán. Although the content referring to contemporary politics was much smaller, not so the anachronistic objects that populate the scenery. Meanwhile, José Frade, the creator of the invention, returned to the fray with a film very similar to Joan the Mad, but set in the Middle Ages, The infuriating Cid (1983), directed by Angelino Fons, but again with the omnipresent Alonso Millán as screenwriter (Spanish Cinema, 1983). The specialized critics did not take it long to tear it apart, but the critic Diego Galán in El País, on December 12, 1983, recognized José Frade as the creator of this “undoubtedly profitable comedy formula”, however, audience attendance and box office receipts were not as expected (370.469 spectators and 468.283.76 Euros) and Frade abandoned “the invention”. However, there was still a final act, oblivious to Frade and Alonso Millán, When Almanzor lost the drum (1984) where all the seen topics came together, the reef being considered exhausted. Gone were other projects emerged in the full drunken success of Christopher Columbus, Alonso Millán himself confessed to the journalist José María Amilibia in the ABC pages on September 8, 1983, when Joan the Mad was about be released, his intention to do all the history of Spain, in two films, Goodbye my dear Spain, as the copla by Antonio Molina (Cinema for Reading, 1983).

Parallel to this commercial and popular cinema, “La Españolada” had its days numbered. The arrival of the socialist party in power in 1982 brought with it the appointment of Pilar Miró as Director General of Cinematography in December 1982 (García Santamaría). One of the many other legislative measures taken in this period was the development of the well-known “Miró Law”, the main objective of which was the production of quality films. To this end, different instruments were articulated, such as a film rating board, and the one never seen to date, the granting of subsidies to finance the production of these films, that is, the board with its quality criteria financed a certain cinema, leaving the commercial cinema that until that moment filled the movie theaters outside of that game (Utrera Macías, 2005).

From this period on, although the cinema gained in quality, the decline of screen share of Spanish cinema dropped drastically from 22.9% in 1982 to a ridiculous 7.5% in 1989. From 1982 to 1985, there was a massive closing of movie theaters, the majority being concentrated in the urban centers, that favored the attendance of a more cultured public, the production of popular or “vulgar” films or staying without their traditional places of consumption (neighborhood movie theaters, small populations, which closed many times), and directly expelled from the newly emerged system (Zunzunegui, 1987).

4.2. The history of a country in an anachronistic perspective. Joan theMad… once in a while an expanded universe

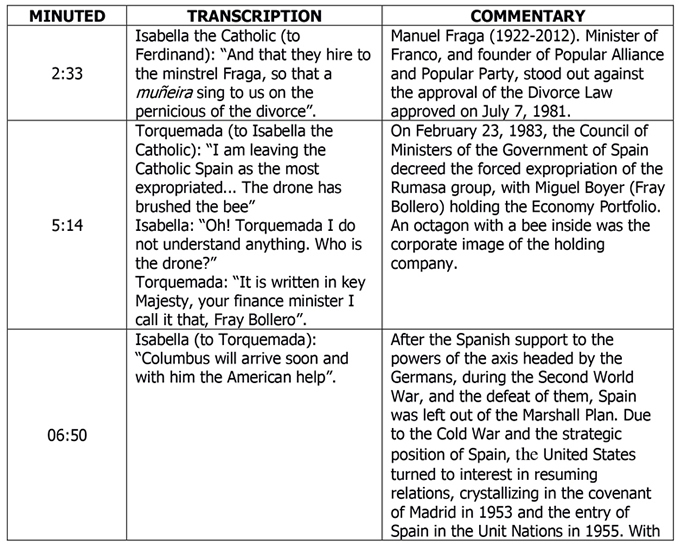

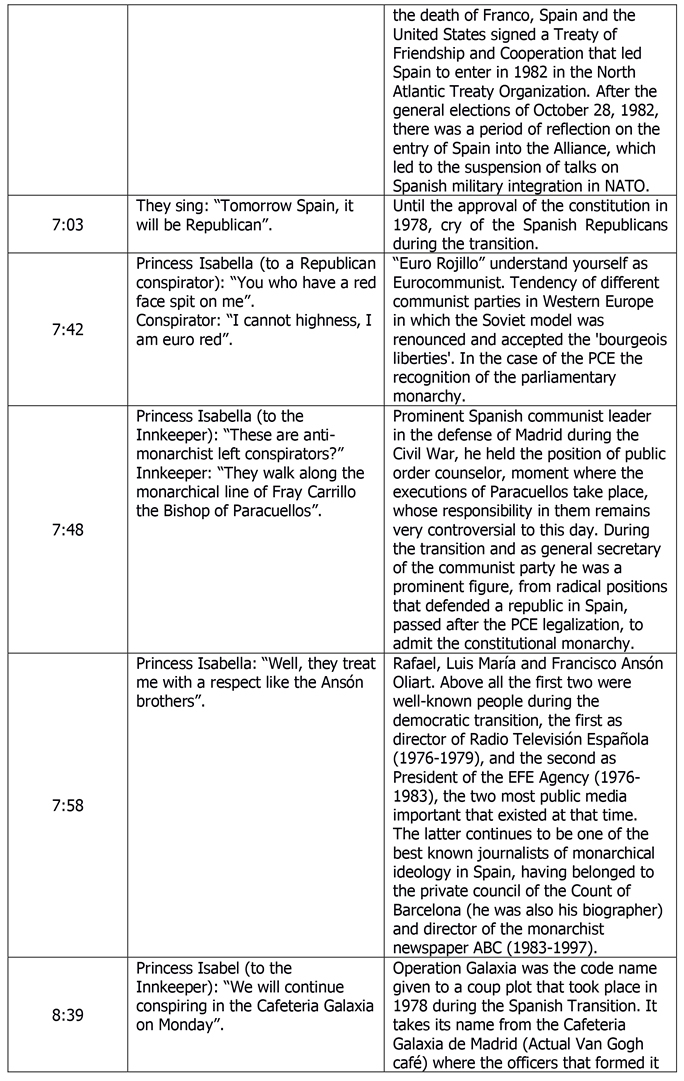

Table 1

Source: Own elaboration.

4.3. The world of objects in Joan the Mad... once in a while

Table 2

Source: Own elaboration.

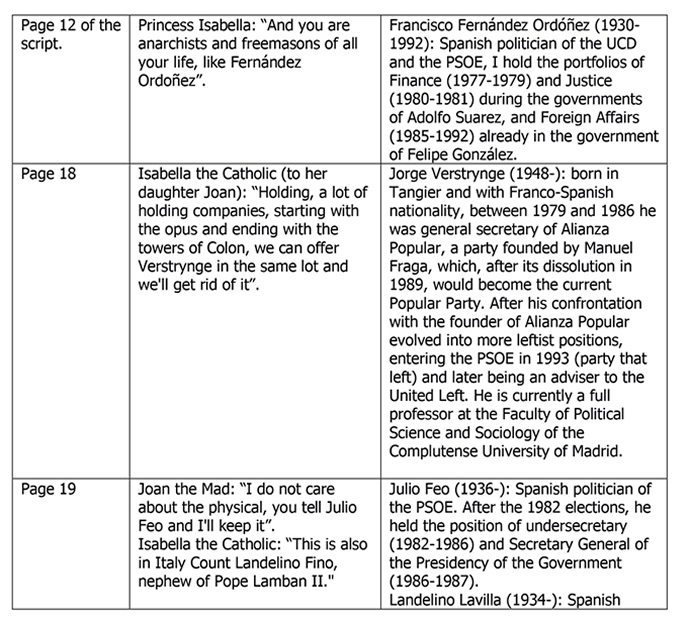

4.4. The script of the film, stories that were not told

Anyway, what was written by Alonso Millán in the script, what was seen on the screen there were substantial changes. Many jokes were left unseen by the spectators, some scenes although shot were never mounted (poisoning cabinet of Joan the Mad), interview of Torquemada with the transcript of the Minister Miguel Boyer, Fray Bollero (Manuel de Blas, disappeared in the definitive movie) at the expense of the social insurance of the same, among others) were added new sequences (dream of Joan), or the songs themselves, whose lyrics are not in it, and other references to contemporary politics were eliminated. It would be tedious to list all these changes, and it is not the objective of the article, since it is our aim to focus on a finished film, but we want to highlight those contemporary characters of the first eighties, who were not mentioned at all (Benet Ferrando, 2012).

Table 3

Source: Own elaboration.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The analysis made has allowed us to verify that each and every one of the criticisms made to the film during its premiere and exhibition, certainly, as far as its script is concerned, come to coincide with reality. However, with the perspective of time given by the 35 years that have passed since the premiere of the film, what to others was a cinematic tragedy, has become to us an essential historical source to understand a fundamental period of our recent history. Joan the Mad... once in a while, is a masterpiece from the of historical viewpoint, since its screenwriter, Juan José Alonso Millán, was able to concentrate in the 77 minutes that the film lasts the worldview about his own world, in a broad cultural, political, ideological, judicial, legislative, social, artistic, mechanical, technological aspect.

The film has a multitude of audiovisual, expressive and communicative codes, which make it impossible for them to be understood today by those who did not live at the time of the making of the film. The analysis here is to provide a small manual of understanding the history of the Spanish Transition.

If the critics of the time already showed the political, social or legislative contents of the film, we have recorded up to 61 references to a multitude of differentiated facts, of a different nature. Their contextualization has allowed us to expand the universe of Joan the Mad... once in a while, until unsuspected limits until now.

In table two, we have referenced up to 27 objects distributed in the 77 minutes of the film, of various kinds, technological objects to play video or music; bottles and drinks of the time; allusions to the press and magazines, etc. They all hide a story and expand the universe of Joan the Mad.

If the great amount of information that the analysis of the films has offered us has allowed us to approach the film as a source of privileged information and as an exceptional historical document, the possibility of analyzing the original script and being able to compare it with the final film has allowed us to become aware of the changes produced between one and the other, since originally there were many scenes that were planned and that were finally not included. We have detected up to 8 different omissions that appeared in the script and that were finally not included in the movie. These omissions were mostly related to political personalities of the time, but also to journalists and musicians. We believe that it is important to recover the presence of these names, who, had they appeared in the film, would have enriched, even more, the historical document under study.

REFERENCES

1. Benet Ferrando, V. J. (2012). El cine español: Una historia cultural. Barcelona: Paidós.

2. Dirección General de Cinematografía. Cine Español, 1983. Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura 1983.

3. Del Amo, Á. (2009). La comedía cinematográfica española. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2009.

4. García Barrientos, J. L. (2004). Teatro y Ficción. Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos.

5. González González, L. M. (2009). Fascismo, “kitsch” y cine histórico español (1939-1953). Cuenca: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha.

6. Guerra Gómez, A. (2012). El rostro amable de la represión. Comedia popular y “landismo” como imaginarios en el cine tardofranquista. Hispania Nova: Revista de historia contemporánea, 10.

7. Huerta Floriano, M. Á., & Pérez Morán, E. (2015). De la comedia popular tardofranquista a la comedia urbana de la transición: Tradición y modernidad. Historia Actual Online, 37, 201-212.

8. López Gandía, J., & Pedraza, P. (1989). El rey de Burlas: la risa en la comedia española de los ‘80. En Escritos sobre el cine español: 1973-1987, 133-148. Valencia: Institut Valencià d´Arts Escéniques, Cinematografia i Música, Filmoteca de la Generalitat Valenciana.

9. Losilla Alcalde, C. (1999). Tan lejos, tan cerca: La representación de la historia y la historia como representación en el cine español de los años ochenta y noventa. Cuadernos de la Academia, 6, 117-126.

10. Martínez Montalbán, J. L. (1989). Cine. En Doce años de cultura española (1976-1987). Madrid: Ediciones Encuentro.

11. Monterde, J. E. (1993). Veinte años de cine español (1973-1992): Un cine bajo la paradoja. Madrid: Paidós.

12. Montoya, A.; Ponga, P.; Salvans, R., & Torreiro, M. (2015). Especial comedia española, el eterno filón de la comedia. Fotogramas & DVD: la primera revista de cine 2060, 86-98.

13. Payán, M. J. (2007). La historia de España a través del cine. Madrid: Cacitel.

14. Pérez Gómez, Á. A.; & Equipo Reseña (1984). Cine para Leer, 1983: Historia crítica de un año de cine. Bilbao: Editorial Mensajero.

15. Torres, A. M. (1992). Gracias y desgracias del cine español de los ochenta. Claves de razón práctica, 22, 64-68.

16. Utrera Macías, R. (2005). El concepto de cine nacional: Hacia otra historia del cine español. Comunicación: Revista Internacional de Comunicación Audiovisual, Publicidad y Estudios Culturales, 3, 83-100.

17. Vidales Gonzáles, C. E. (2009). La relación entre la semiótica y los estudios de la comunicación; un diálogo por construir. Comunicación y sociedad, 11.

18. Zunzunegui, S. (2002). Historias de España. De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de cine español. Valencia: Ediciones de la Filmoteca.

19. Zunzunegui, S. (2005). Los felices sesenta: Aventuras y desventuras del cine español (1959-1971). Barcelona: Paidós.

AUTHORS

Antonio Rafael Fernández Paradas: Doctor in History of Art from the University of Malaga, with a doctoral thesis entitled Historiography and methodologies of the History of Furniture in Spain (1872-2011). A state of affairs. Graduated in History of Art and degree in Documentation from the University of Granada. Master in Appraisal and Appraisal of Antiques and Works of Art by the University of Alcalá de Henares. He is currently assistant professor doctor of the University of Granada, where he teaches in the Department of Social Science Didactics of the Faculty of Education Sciences, and teacher of the master’s Art and Publicity of the University of Vigo.

antonioparadas@ugr.es

Rubén Sánchez Guzmán: Degree in Art History from the Autonomous University of Madrid. At present, he is a professor of Art History and to Know Madrid in the Cultural Centers of the Madrid City Council (Educo-Actividades). He has been a teacher of the 1st master in Spanish Baroque Sculpture. From the golden centuries the information society and social networks taught by the International University of Andalusia. Expert appraiser in antiques and works of art in the art department and auction room Lamas Bolaño in Madrid, performing functions of appraisal, cataloging and personalized advice.

ruben_sanguzman@hotmail.com