doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.48.149-171

RESEARCH

TRANSPARENCY AS A REPUTATIONAL VARIABLE OF THE CRISIS COMMUNICATION IN THE MEDIA CONTEXT OF WANNACRY CYBERATTACK

LA TRANSPARENCIA COMO VARIABLE REPUTACIONAL DE LA COMUNICACIÓN DE CRISIS EN EL CONTEXTO MEDIÁTICO DEL CIBERATAQUE WANNACRY

A TRANSPARÊNCIA COMO VARIÁVEL REPUTACIONAL DA COMUNICAÇÃO DE CRISES NO CONTEXTO MEDIÁTICO DO CIBER ATAQUE WANNACRY

Luis Mañas-Viniegra1, José Ignacio Niño González1, Luz Martínez Martínez2

1Complutense University of Madrid. Spain.

2Luz Martínez Martínez: Rey Juan Carlos University. Spain.

ABSTRACT

This piece of research analyzes the media context of the WannaCry cyberattack in relation to the crisis communication carried out by Telefónica with respect to that exercised in the Telecommunications sector, applying, in two intervals of the cyberattack, the grounded theory to the media discourse of the press. Despite the improvable reputation of the corporate brands in the Telecommunications sector, the immediate reaction, the informative transparency exerted, the collaboration with public bodies and others affected and a quick solution to the cyberattack are the fundamental categories on which a stronger reputation than that of its direct competition has been built during the crisis communication, transferring the traditional official spokesperson to the social networks of one of its directors. The negative feeling of 14% that emerges from the media discourse during the first wave of cyberattack coincides with the 12% shown by citizens on Twitter, so the published opinion is consistent with the opinion of the public. Despite this, there is a greater incidence of the negative approach in the “confidential” digital newspapers, less exposed to the advertising pressure of the large corporate brands and more to the loss of journalistic values ??alluded to in the scientific literature.

KEY WORDS: WannaCry – media analysis – crisis communication – reputation – corporate brand – transparency – social networks.

RESUMEN

Esta investigación analiza el contexto mediático del ciberataque WannaCry en relación con la comunicación de crisis llevada a cabo por Telefónica con respecto a la ejercida en el sector de Telecomunicaciones, aplicando en dos intervalos del ciberataque la teoría fundamentada o grounded theory al discurso mediático de la prensa. A pesar de la mejorable reputación de las marcas corporativas en el sector de Telecomunicaciones, la reacción inmediata, la transparencia informativa ejercida, la colaboración con los organismos públicos y otros afectados y una rápida solución al ciberataque son las categorías fundamentales sobre las que se ha construido una reputación más sólida que la de su competencia directa durante la comunicación de crisis, trasladando la tradicional portavocía oficial a las redes sociales de uno de sus directivos. El sentimiento negativo del 14% que emerge del discurso mediático durante la primera oleada del ciberataque coincide con el 12% mostrado por la ciudadanía en Twitter, por lo que la opinión publicada es coherente con la opinión de los públicos. A pesar de ello, se observa una mayor incidencia del enfoque negativo en los diarios digitales “confidenciales”, menos expuestos a la presión publicitaria de las grandes marcas corporativas y más a la pérdida de valores periodísticos aludida en la literatura científica.

PALABRAS CLAVE: WannaCry – análisis mediático – comunicación de crisis – reputación – marca corporativa – transparencia – redes sociales.

RESUME

Esta investigação analisa o contexto mediático do ciber ataque WannaCry em relação com a comunicação de crises levada a cabo por Telefônica com respeito a exercida no setor de Telecomunicações, aplicando em dois intervalos de ciber ataque a teoria fundamentada ou grounded theory ao discurso mediático da imprensa. Apesar da melhorável reputação das marcas coorporativas no setor de Telecomunicações, a reação imediata, a transparência informativa exercida, a colaboração com os organismos públicos e outros afetados e uma rápida solução ao ciber ataque são as categorias fundamentais sobre as que foram construídas uma reputação mais solida que a de sua concorrente direta durante a comunicação de crises, trasladando a tradicionais porta vozes oficial as redes sociais de um de seus diretivos. O sentimento negativo de 14% que emerge do discurso mediático durante a primeira oleada de ciber ataque coincide com 12% mostrado pela cidadania em Twitter, pelo qual a opinião publicada é coerente com a opinião dos públicos. Apesar disso, se observa uma maior incidência do enfoque negativo nas notícias digitais “confidenciais”, menos expostos a pressão publicitaria das grandes marcas coorporativas e mais a perda de valores jornalísticas aludida na literatura cientifica.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: WannaCry – analises mediática – comunicação de crises – reputação – marcas coorporativas – transparência – redes sociais.

Correspondence: Luis Mañas-Viniegra: Complutense University of Madrid. Spain.

lmanas@ucm.es

José Ignacio Niño González: Complutense University of Madrid. Spain.

josenino@ucm.es

Luz Martínez Martínez: Rey Juan Carlos University. Spain.

luz.martinez@urjc.es

Received: 14/08/2018

Accepted: 09/01/2019

Published: 15/03/2019

1. INTRODUCTION

The media have a significant influence on the public’s interpretation of a crisis, especially those prior to the digital ecosystem. Depending on the selection of topics that make up the agenda-setting (Shaw, 1979, Wolf, 1994), each day the gatekeepers decide whether or not to block certain information (Barzilai - Nahon, 2008). Together with the effects of the frame from which the reality or framing is observed (Hanggli & Kriesi, 2012) and selective exposure (Rubin, 1996), they can cause a positive correlation between the number of published news and greater concern on the part of citizenship (Igartua, Otero, Muñiz, Cheng, & Gómez, 2007).

However, the loss of values ??suffered by a part of the journalistic profession, among which “contrast, rigor, honesty and quality” stand out (Gómez-Mompart, Gutiérrez-Lozano, & Palau-Sampio, 2015, p. 147) and scarce political and economic independence (Madrid Press Association, 2014), have caused the information published about companies in crisis situations not to correspond sometimes with the interpretation of the situation the rest do of publics make and usually express on social networks. This paradox causes the published opinion not always to correspond with the opinion of the public, which is precisely one of the questions that this piece of research tries to clarify in relation to the case study. In relation to that economic independence, we cannot ignore that Telefónica is the eleventh largest advertiser in Spain (Sánchez-Revilla, 2017), in line with other major operators in the telecommunications sector, since both Vodafone and Orange are in the top 10 of advertisers.

The large organizations have passed from competing as product brands to becoming corporate brands (Olins, 2009) dissociated from the products and oriented towards their stakeholders (Freeman, 1984) based on models of behavior they project onto society, some of them becoming references for it (Benavides-Delgado, 2015), where reputation, transparency, social responsibility and good corporate governance are essential components. Reputation is based on perception (Gaine-Ross, 2003), recognition (Ferguson, Deephouse, & Ferguson, 2000) or participation (Aaker, 1996) of stakeholders, who evaluate the personality or corporate identity, with a structural character that allows lasting effects (Villafañe, 2012). The systemic approach of the organizations also promotes reciprocal relations between the organization and its public (Xifra, 2005), so that a bidirectional symmetric model (Grunig & Hunt, 1984) is established in communication.

Despite the variety of crises that can affect an organization, there are elements that are reiterated, such as lack of foresight, insufficient initial information in the face of events that happen quickly and to which we must respond urgently, or the interest of the media, the image and reputation of different audiences being affected: victims, employees, customers, public authorities, the media audience or the organization itself, among other external and internal ones (Cervera-Fantoni, 2008; Castillo-Esparcia, 2010), considering that it is necessary to harmonize the interests of the organization with those of its public (Costa, 2004).

The uncertainty scenario that leads to any crisis causes an increase in the information pressure on the part of the media, citizens and employees, which negatively affects the relation between the company and its stakeholders (Van-der-Meer, Verhoeven, Beentjes, & Vliegenthart, 2017). It is this tension which usually leads to precipitation and mistakes in crisis communication and, therefore, the Director General or CEO of the company continues to be the spokesperson who can be more credible when the right reputation is available (Kim & Park, 2017), although always in coordination with the dircom (Grunig, Grunig, & Dozier, 2002), which, in the case of Telefónica, reports directly to the Presidency (Recalde & Gutiérrez-García, 2017). Despite these tensions, in order to protect the reputation, it is essential that the first statements of the company occur quickly, be transparent, provide accurate information and reassure the public that may be affected (Woods, 2016), paying adequate attention to the evaluations carried out by the media, citizens and other stakeholders (Romero-Rodríguez, Torres-Toukoumidis, & Pérez-Rodríguez, 2017).

The arrival of social networks had a decisive influence on the asymmetric relation that existed between companies and stakeholders in crisis communication, allowing them to access information that the former used to hide when they could foresee that it would harm their image (Castillo-Esparcia & Ponce, 2015). Precisely the loss of credibility, trust and reputation are consequences of inadequate crisis management (Capriotti, 1999; Villafañe, 2008).

Communicative hostility (Castillo-Esparcia & Ponce, 2015) is a negative behavior towards the organization that affects its credibility and reputation as the public’s attention focuses on a specific aspect of the situation that has caused the crisis, which has arisen in many occasions from the publication of information that was unknown or from the very response that the organization gives to the fact that originates the crisis. That the brands in social networks usually respond quickly to the mentions they receive (Aced, 2013), implies the risk that the team of community managers will provide information or issue a response without having considered that it is in a crisis situation, despite the need to respond to a crisis 2.0 with speed, visibility and credibility (Bollero, 2008). In any case, crisis communication in the digital ecosystem implies a continuous change that implies a revision of existing theories and taxonomies (García-Ponce & Smolak-Lozano, 2013).

In a situation of current crisis communication, both the agenda-setting and the framing of the media should be contrasted with the opinions expressed by stakeholders in social networks to assess how the perception of the public evolves on the situation, so that they adapt the responses of the organization in order to preserve its reputation (Coombs, 2007, Coombs, & Holladay, 2012, Bowen & Zheng, 2015).

The importance of the crisis generated by WannaCry cyberattack lies in the alteration of some guiding principles of communication management that have traditionally been followed by organizations (Westphalen & Piñuel, 1993; Luecke, 2005): taking the initiative in communication with a single appointed spokesperson to avoid the formation of rumors, providing details of what happened without providing false information or evading responsibility, maintaining the credibility with public apologies for what happened and initiating concrete measures to alleviate its effects and avoid that it can occur again in the future.

1.1. The context of the organization

In 1924, the National Telephone Company of Spain (Telefónica) was created to provide a telephony service that would operate as a monopoly, leading in the 70s an unprecedented internationalization among Spanish companies and starting to trade on the New York Stock Exchange in 1987 (Calvo-Calvo, 2010). However, the liberalization directives of the currently so-called European Union, aimed at dissolving monopolies in basic services, led Telefónica to privatize itself and have to compete in free competition since 1998 with new companies that emerged at the height of the mobile telephony and Internet (Bel & Trillas, 2005). The consequence was a bloody commercial war that lasted for more than a decade and that led to a notable loss of reputation on the part of Telefónica (Calzada & Estruch, 2011) and, in general, of the entire Telecommunications sector. It was at that moment when the Company understood the need to innovate and educate in innovation to become the current integrated telecommunications operator, improve customer satisfaction and develop a decided policy of corporate social responsibility (Palacios-Marqués & Devece-Caranana, 2013), decisions that have allowed its conversion into an authentic multinational corporation (Clifton, Comin, & Díaz-Fuentes, 2011).

Accordingly, the entity undertook a restructuring of its brand architecture that would allow the gradual recovery of its corporate reputation, simplifying a tangle of brands whose origins were the acquisitions and mergers carried out prior to the dotcom crisis in the year 2000. This way, the product brands were reduced to Movistar, O2 and Vivo, dissociating them from the corporate brand Telefónica and focusing the latter on corporate values ??consistent with “respect, quality and transparency” (Telefónica, 2016), its social responsibility and a good organization of corporate governance in search for a better relationship with citizens and obtaining a better reputation.

Despite the fact that the product brand Movistar is ranked 43 worldwide, with a valuation of more than 22,000 million dollars (Kantar MillwardBrown, 2017), the corporate brand Telefónica is not among the 50 companies with the best reputation in Spain. (RepTrak, 2017) or among the top 100 in the world (RepTrak, 2017a), so the reputational issue continues to be vulnerable in its strategic management. Similarly, the Telecommunications sector itself has the worst reputation of all, with 56.0 points, which RepTrak considers weak without having to compare it with other sectors.

1.2. WannaCry cyberattack

On May 12, 2017, a worldwide cyberattack began with a malicious software or malware called WannaCry, which affected several Spanish companies by blocking their communications networks and asking for a ransom for their release, hence the name ransomware. The news, which initially appeared in the media without official confirmation, soon incorporated Telefónica as the most affected after ratification by internal sources, while other companies that were cited as attacked denied it outright, such as Vodafone, BBVA or Capgemini. A third group of companies, such as Iberdrola or Gas Natural, only acknowledged having turned off their equipment as a preventive measure. The Security and Industry Incident Response Center (CERTSI), under the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Industry, officially confirmed that Spain had suffered the WannaCry cyberattack, although without mentioning the affected companies.

WannaCry cyberattack has aroused the interest of researchers, although limited to issues such as its technological analysis (Krunal & Kumar, 2017, Mourle & Patil, 2017, Woods, Agrafiotis, & Jason, 2017), the proposal to use the Blockchain technology, which sends and encrypts information separated by blocks, the consideration of cybersecurity as a human right (Shackelford, 2017), the consequences it has had for patients of the British health service or NHS (Clarke & Youngstein, 2017; Ehrenfeld, 2017) or the criminal responsibilities that could arise from the compliance perspective (Cain et al., 2017).

This type of cyberattacks is not new and their immediate effect on corporations is known after the precedents suffered by Google in 2010 (Jacobs & Helft, 2010) or by Sony Pictures in 2014 (Barnes & Cieply, 2014): the paralysis of its system computer and the request for the payment of a ransom. However, beyond the merely economic-financial effects and technical stoppage of the processes of the companies, of ephemeral duration, the reputational crises that may arise are the real problem they face. Poor management of crisis communication is usually the trigger for a reputational crisis.

It is common for companies to make these cyberattacks public days after having suffered them, showing control of the situation and minimizing the consequences. That is why their stakeholders usually demand greater transparency, since the personal data of customers, suppliers or employees themselves may have been exposed, a fact that is often omitted. This happened in the cited case of Google, which was a lesson learned to expressly report on this issue when it suffered a new cyberattack the following year. In another attack suffered by Sony in 2011, it took six days for the Company to report that the personal data of 77 million users had been exposed, including the records of their credit cards (Delclós, 2011).

In this sense, the official confirmation by Telefónica occurred the same morning of the attack through a brief aseptic 5-line statement in its online press room which claimed to have detected a cybersecurity incident that has affected the PCs of some employees of the internal corporate network of the company. Immediately, the security protocol for this type of incidents has been activated with the intention that the affected computers operate normally as soon as possible (Telefónica, 2017). Telefónica was the first company to recognize the attack, it communicated said attack transparently and collaborated with public bodies in the ransomware solution, a fact that was recognized in a press release by the National Institute of Cybersecurity (INCIBE) and with the Chief Data Officer (CDO) of Telefónica being awarded the White medal of the Civil Guard for his collaboration.

In WannaCry cyberattack suffered by Telefónica, the spokesperson informally assumed it through his Twitter account his CDO, the only person of the Company who made any kind of identified statement, although, surprisingly, it was to indicate that “the internal security of Telefónica is not one of my direct responsibilities, but we are all part of security at home, the news is exaggerated”. Criticism occurred immediately in the media and social media, since Telefónica website itself indicates his hierarchical dependence on the Presidency and his functions as “responsible for global cybersecurity and data security”. He also added that he was on vacation, although helping remotely.

There are numerous crises in which, mistakenly, the leader blames the negligence of its employees (Volkswagen and its toxic emissions), the invention of the media (Donald Trump) or the victims themselves (Ebola crisis in Spain), typical defensive strategies (Coombs & Holladay, 2010). However, the situation in which the spokesperson carries out an example of transparency by announcing a crisis that affects the corporate brand and then evading any type of responsibility, even when being the maximum responsible person for its prevention, initiating the possibility of a reputational crisis within crisis communication, is unusual.

On May 19, the CDO of Telefónica published an entry in his personal blog in which he clarified his responsibilities, vacation, successes and errors in managing the cyberattack, in a new display of transparency and naturalness in the communication of the crisis that were unknown in other crises previous to the digital ecosystem.

2. OBJECTIVES

This piece of research quantitatively and qualitatively analyzes the crisis communication by Telefónica due to the infection of its computer systems by WannaCry cyberattack, comparing the focus of the information published by the Spanish press with the feeling of its audiences on Twitter.

The specific objectives are:

Identify the information published in the national press about the organization during the cyberattack.

Analyze the content and discourse of the information to identify the positive, negative or neutral approach used.

Identify the novel elements of crisis communication by Telefónica with influence on its reputation.

Perform a feeling analysis of Telefónica on Twitter during the cyberattack.

Determine if the published opinion matches the opinion of the public.

3. METHODOLOGY

For the achievement of the objectives, the grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967, Strauss & Corbin, 1990, Glaser, 1992, Locke, 2001, Douglas 2004, Blythe, 2007) is used as a methodology because of its explanatory nature of behaviors in organizations and social discourses, starting without any hypothesis that may condition the results before saturating the categories in the identification of redundant concepts in discourse analysis (Benavides-Delgado, 2005).

The two waves in crisis communication by Telefónica due to WannaCry cyberattack are analyzed. The first covers from May 12 to May 18, 2017, that is, from the infection with WannaCry ransomware until the effects in Spain disappear completely, which is the week of the reputational crisis. The second begins on May 19, after entry published on his blog by Telefónica CDO, until the end of May.

On the one hand, the information published by the press on the subject is analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively with the support of Atlas.ti and.6.2 software. The sample consists of three groups of printed media. A first group is made up of the five main daily national newspapers: El País, La Vanguardia, El Mundo, ABC and La Razón. The second group consists of the entire economic press: Expansión, Cinco Días and El Economista. A third group consists of the five main digital newspapers that usually focus on “confidential” information: El Confidencial, Ok Diario, Libertad Digital, Eldiario.es and Voz Populi. Their digital versions were accessed because they had a greater profusion of news than the printed version and the information in which the keywords “ransomware”, “WannaCry” or “cyberattack” without Telefónica being present was deleted, since its content was purely technological.

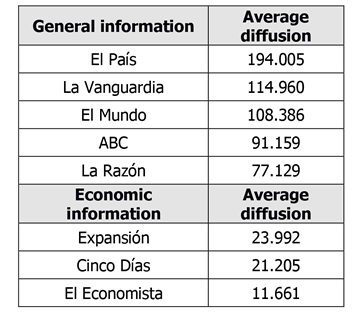

The sample design is based on the selection made on the basis of the 2016 dissemination data (OJD, 2017) of the five main national newspapers and the entire economic press.

Table 1. Average of diffusion year 2016 of national newspapers and economic press in Spain.

Source: Own elaboration from OJD (2017).

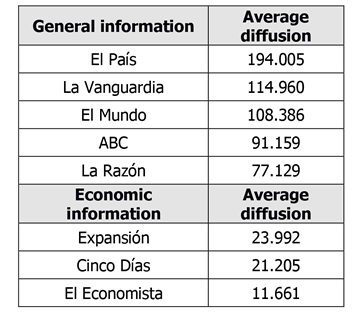

In the case of confidential digital newspapers, the selection of the five newspapers is based on the data of unique visitors at the end of March 2017 (Comscore, 2017):

Table 2. Unique users, year 2016, of “confidential” digital newspapers.

Source: Own elaboration based on Comscore MMX (2017).

In the first interval (i1), there are 173 valid pieces of information (93.51% of the total), as compared to 12 (6.49%) of the second interval (i2), according to the following distribution:

Table 3. Distribution of the number of information published per interval.

Source: Own elaboration.

The content was cataloged in 3 families: positive, neutral and negative reputation, which, in turn, are ordered in hermeneutical units for each interval. The coding system we used has been inductive or bottom-up, starting with the data to arrive at the codes.

On the other hand, a feeling analysis of the brand Telefónica is carried out in comparison with that of its competitor Vodafone - implied in the cyberattack without official recognition - from the content of the published tweets, evaluated by peers by the authors with the objective to contrast the opinion published by the press with that of other stakeholders, which are extended to the whole of society with presence on Twitter, often the most critical. Feeling analysis is carried out with the technological support of Twitter API based on the tweets published on May 12, 2017, as this is the first day of the crisis and the one with the greatest virulence for the brand, thus isolating the effect of its transparency and the spokesperson exercised in social networks in the most negative possible scenario with respect to the rest of the days when crisis communication was managed.

4. DISCUSSION

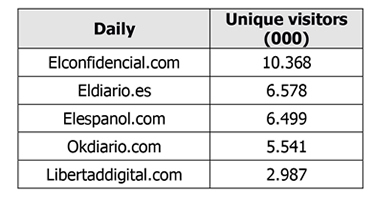

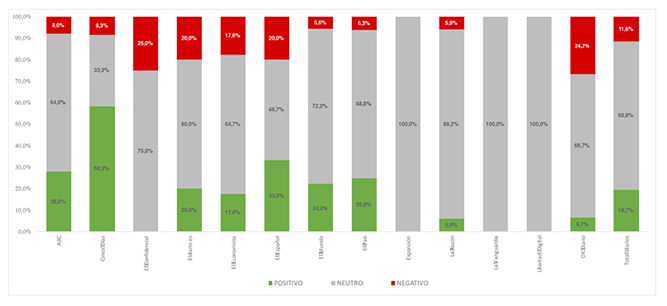

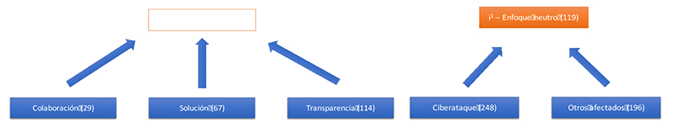

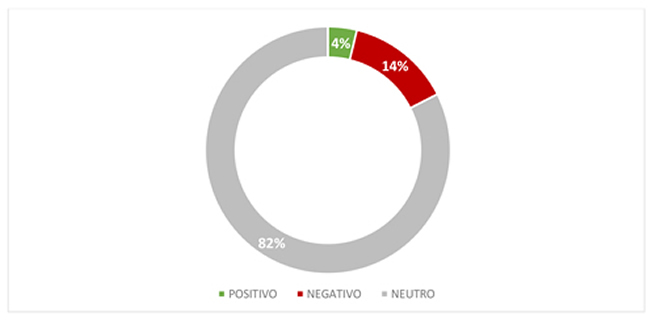

The hermeneutic unit i1, the main one, made it possible to establish three families based on the approach adopted mainly for each piece of information in which Telefónica was expressly mentioned in relation to the cyberattack: positive approach (34 reports, 19.65% of the total), neutral approach (119, 68.79%) and negative approach (20, 11.56%). We must consider that suffering a cyberattack is, per se, a negative fact, but we have considered the general tone of each piece of information and the predominance of some elements over others, whether negative or positive. In addition, it can clearly be seen in the following graph how information with a negative approach is more frequent in “confidential” digital newspapers, which show less dependence on the advertising revenues of large brands such as Telefónica.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 1. Types of speeches by newspapers and in total in interval i1.

In the first family, that of the positive approach, content analysis has allowed us to codify three categories that construct a positive discourse. The first one is the collaboration of Telefónica with INCIBE and with other companies to find a solution to the cyberattack in Spain, with 29 mentions. The second is the information discourse of control of the situation, which, in most of the information, is linked to the solution of the infection, with 67 mentions. Third, there is recognition, and sometimes praise, of the transparency shown by the Company, warning of the attack and publicly recognizing it since the first moment, unlike the rest of the Spanish affected companies, which claimed to have turned off their equipment for mere caution. Worldwide, only Renault acted with the same transparency in its crisis communication. Transparency is reflected in 114 mentions.

The neutral approach constitutes the second family, two categories being detected on the basis of the codification of the information in which Telefónica is expressly mentioned: “cyberattack”, with 248 mentions that represent 69% of the information, refers to an approach to the information in which the events that occurred are reported without an express opinion on the performance or vulnerability of the Company. The second category mentions other affected companies or organizations on 196 occasions, granting them more space, in most cases, than Telefónica, especially in the case of NHS due to its international impact and greater incidence on citizens.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 2. Relationship diagram i 1 -positive and neutral approach.

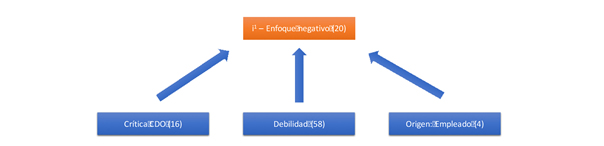

The negative approach hardly appears in 20 reports, 12% of the total, a fact that reflects by itself adequate management of crisis communication, at least in its relationship with the press. The strictly negative information adopts a critical approach, sometimes close to satire, to the attitude of the CDO of Telefónica (16 mentions) to avoid responsibilities in its Twitter account, the weakness that implies, in the middle of the digital age, to announce to all employees by public-address system to turn off their computers and stop working until a new order is issued (58 mentions), regardless of the fact that a company of such magnitude is infected and, lastly, the focus of the crisis on the irresponsibility of an employee who opened the electronic mail that contained the virus, only with 4 mentions.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 3. Relationship diagram i 1 -negative focus.

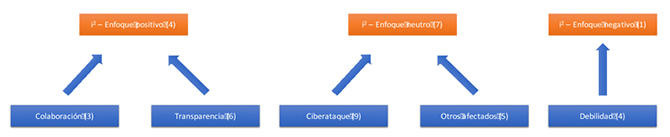

The hermeneutic unit i2 clearly reflects how information interest declines and moves away from Telefónica with only 12 pieces of information, of which only one (8%) is negative, as a consequence of the weakness shown by a company of its magnitude. There is no longer any code on the criticisms of the CDO, which have been neutralized with their explanations. Once again, the neutral approach predominates with 7 pieces of information and the positive one represents 33% of the information of this second period, transparency standing out again, with six mentions, only behind the codes that belong to the neutral approach: “cyberattack” (9 mentions) and “others affected” (5).

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 4. Relationship diagram i 2.

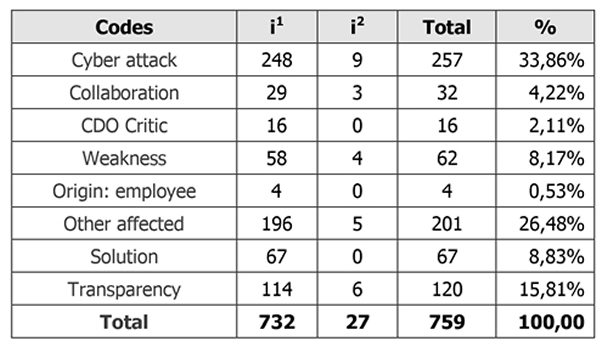

Regarding the total reiteration of the codes in the information, the neutral codes represent 60.34% of the total, the positive ones, 28.85% and the negative ones, only 10.80%. The preeminent codes are “cyberattack” (33.86%), “others affected” (26.48%) and “transparency” (15.81%). The data confirm again the importance of the rapid communication and assumption of cyberattack by Telefónica in managing the crisis, avoiding a reputational impact on the published information.

Table 4. Frequency of codes in information published by interval.

Source: Own elaboration.

Exhausting the analysis of the crisis communication carried out due to the cyberattack suffered in the press would mean limiting the importance of the rest of the stakeholders in the reinforcement or deterioration of that still fragile reputation of the corporate brand Telefónica.

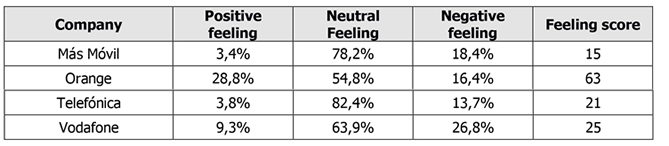

The feeling analysis on Twitter on the day of the cyberattack, carried out with the same criteria as the analysis of the information, confirms how effectively the boast of transparency and collaboration carried out has served to neutralize the negative effects on public opinion of the weakness or initial attitude of the CDO when it comes to shirking responsibilities. 3.8% of tweets reflect a positive feeling, 82.4% neutral and 13.7% negative. The feeling score, which is calculated by dividing the positive tweets exclusively by the sum of the positive and negative ones, is 21.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 5. Feeling analysis by Telefónica during the cyberattack.

In the state of the art, we already warned about the reputational problems of Telefónica as a result of the fierce competition experienced by the telecommunications sector for more than a decade. For this reason, and even having dissociated its product brands from its corporate brand, even today there are criticisms of Movistar consumers in their tweets, alluding to Telefónica, so a longer period of time is still necessary for all publics to appreciate this difference. We must also consider that Telefónica is a publicly traded company and that increases or decreases in its daily price also affect the tweets that are published on it, not as a brand, but as a listed company on whose evolution the equity of millions of shareholders depends. Precisely because, even contemplating all these conditions, the 13.7% of negative feeling might seem very high reputationally in absolute terms, we must make a comparison with its competition and with other reputable brands belonging to other sectors not affected by the cyberattack. We must remember that Telefónica is not among the most reputable brands internationally, not even in Spain, a fundamental issue when facing a crisis strongly. This way, compared to 13.7% of Telefónica’s negative feeling, Renault only showed a negative 2.7% and a positive 8.4%, figures that were much more reputationally strong than those of Telefónica, especially considering that Renault was the other great brand that recognized suffering the attack since the first moment and that started from position 87 worldwide in the Global RepTrak 2017 (Reputation Institute, 2017). However, when comparing Telefónica’s feeling analysis with respect to its competition on the day of the cyberattack, we see that it has the least negative feeling, despite being the main protagonist in Spain of the cyberattack in all media, a fact that by itself is negative. As a logical consequence, it also has the lowest positive feeling on the day of the attack, which improves as the crisis is being solved, and also the higher neutral feeling.Vodafone, its main competitor, did not recognize at any time having suffered the attack, despite the fact that all the media said so through unofficial sources. This attitude has a clear reflection of reputational deterioration not picked up by the press but by the feeling analysis carried out on Twitter, with 26.8% of negative feeling, almost twice the one experienced by Telefónica. Neither Orange nor Más Móvil suffered the cyberattack, both showing a disparate behavior. While the positive feeling experienced by Orange rose to 28.8%, the highest of all, Más Móvil data were worse than those of Telefónica, explained by the weak reputation of the entire Telecommunications sector as a result of permanent conflicts that they have with their clients and have already been mentioned.

Table 5. Feeling analysis during the cyberattack

.

Source: Own elaboration.

In short, there seems to be coherence between the agenda and the framing of the press and the feeling analysis of the public on Twitter, despite the fact that the information published by the “confidential” newspapers, less affected by the advertising pressure of the large groups and more permeable to that loss of values ??alluded to in the review of the scientific literature, is considerably more negative. Neither in the information nor in the social networks does the discourse focus on customers as possible affected, which corroborates the importance of the corporate brand over the product brand currently in the large organizations. In relation to management of crisis communication, the organization has reinforced its reputation, scarce in the sector, with an exercise of immediate reaction, transparency and collaboration in accordance with the classic guidelines of the state of the art. However, the great contribution of the case is the transfer of the official spokesperson to social networks and to one of its directors after a brief official statement on the situation, with an agile, transparent and collaborative speech, without hiding information that had occurred. about a fact that there was no control yet and that, on the other hand, employees had already filtered it through their social networks without considering the consequences, becoming the first source of information for the media and reinforcing the lack of foresight and the urgency of the response that the scientific literature has consistently revealed at the beginning of crisis communication.

5. CONCLUSIONS

A solid corporate reputation is the best intangible to face a crisis situation. However, the reputation of corporate brands in the telecommunications sector is poor and this implies greater vulnerability to the WannaCry cyberattack they suffered, which has acquired a notable informative dimension and has captured the interest of stakeholders.Crises are unforeseen due to their very essence and, the day before it occurred, Telefónica announced an increase in its profit of 42% over the previous year and its product brand Movistar communicated to its customers the end of the additional charges for roaming in their travels in Europe. However, this positive information disappeared from the media agenda at the time when a crisis of such magnitude affected the Company. Despite the controversial media independence in relation to the large advertisers that finance their activity, among which is Telefónica, it became the protagonist of the information on the cyberattack in Spain, the neutral approach standing out in 69% of the information published in the first interval, the largest, and the positive approach in 20% of the cases. Despite the small number of negative reports (11% in the first interval and 8% in the second), while the general information press opts mainly for the neutral tone, in the “confidential” newspapers there is a greater incidence of the negative tone. The positive elements in the crisis communication have been transparency, a quick solution to the cyberattack and the collaboration shown with all the agents involved. Among the negative elements are the weakness shown by a large technology company and the initial attitude of the spokesperson eluding their professional responsibilities, which were later clarified in a new exercise of transparency that caused Telefónica to disappear from the media agenda quickly in relation to the cyberattack, with a contribution to the scientific literature on crisis communication based on the rupture of the single official spokesperson and the main management through social networks in an agile, transparent and collaborative manner.As a consequence of all this, the result has been a similar negative feeling in the information published in the press (14%) with respect to that expressed by the public on Twitter (12%), showing a stronger position with respect to the rest of corporate brands in the telecommunications sector, especially with Vodafone, who denied suffering the cyberattack, despite the fact that all the media contradicted it by referring to internal sources, raising their negative feeling on Twitter to 26.8%.

REFERENCES

1. Aaker, D.A. (1996). Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review, 38(3), 102-120.

2. Aced, C. (2013). Relaciones públicas 2.0. Cómo gestionar la comunicación corporativa en el entorno digital. Barcelona: UOC.

3. Asociación de la Prensa de Madrid (2014). Informe anual de la profesión periodística. Madrid: Asociación de la Prensa de Madrid. Recuperado de http://www.apmadrid.es/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/Informe profesion_2014_def_baja.pdf

4. Barnes, B., & Cieply, M. (2014, 29 de noviembre). Intrusion on Sony Unit Prompts a Shutdown of Messaging Systems. New York Times. Recuperado de https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/30/business/media/intrusion-on-sony-unit-prompts-a-shutdown-of-messaging-systems.html?action=click&contentCollection=Media&module=RelatedCoverage®ion=EndOfArticle&pgtype=article

5. Barzilai-Nahon, K. (2008). Toward a theory of network gatekeeping: A framework for exploring information control. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 59(9), 1493-1512. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1002/asi.20857

6. Bel, G., & Trillas, F. (2005). Privatization, corporate control and regulatory reform: the case of Telefónica. Telecommunications Policy, 29(1), 25-51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2004.09.003

7. Benavides-Delgado, J. (2015). La publicidad, la marca y la ética en la construcción de los valores sociales. En J. Benavides, & A. Monfort (Coords.). Comunicación y empresa responsable (pp. 45-58). Pamplona: EUNSA.

8. Benavides-Delgado, J. (2005). Nuevas propuestas para el análisis del lenguaje en los medios, en Questiones publicitarias, 10(1), 13-33. doi: https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qp.154

9. Blythe, J. (2007). Advertising creatives and brand personality: a grounded theory perspective, en Brand Management, 14(4), 284-294. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550071

10. Bollero, D. (2008). Comunicación de crisis: El plan web en una crisis. Revista de Comunicación, 6, 44-48.

11. Bowen, S. A. (2008). Frames of terrorism provided by the news media and potential communication responses. En H. D. O’Hair et al. (eds.), Terrorism: Communication and rhetorical perspectives (pp. 337–358). New Jersey, NY: Hampton.

12. Cain, C. C. et al. (2017). Global ransomware attack: preparation is key. Journal of Health Care Compliance, 19(3), 37-40.

13. Calvo-Calvo, A. (2010). Historia de Telefónica: 1924-1975. Primeras décadas: tecnología, economía y política. Barcelona: Ariel-Fundación Telefónica.

14. Calzada, J., & Estruch, A. (2011). Telefonía móvil en España: regulación y resultados. Cuadernos Económicos de ICE, 81, 39-70. Recuperado de http://www.revistasice.com/CachePDF/CICE_81_39-70__4D2E26DCC881483187872FE9A63999E2.pdf

15. Capriotti, P. (1999). Planificación estratégica de la imagen corporativa. Barcelona: Ariel.

16. Castillo-Esparcia, A., & Ponce, D. G. (2015). Comunicación de Crisis 2.0. Madrid: Fragua.

17. Castillo-Esparcia, A. (2010). Introducción a las Relaciones Públicas. Málaga: Instituto de Investigación en Relaciones Públicas.

18. Cervera-Fantoni, A. L. (2008). Comunicación total. Madrid: ESIC.

19. Clarke, R., & Youngsteing, T. (2017). Cyberattack on Britain’s National Health Service - A wake-up call for modern medicine. The New England Journal of Medicine, 377(5), 409-411. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1706754

20. Clifton, J., Comin, F., & Díaz-Fuentes, D. (2011). From national monopoly to multinational corporation: How regulation shaped the road towards telecommunications internationalisation. Business History, 53(5), 761-781. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2011.599588

21. Comscore (2017). Informe Comscore MMX marzo 2017.

22. Coombs, T. W. (2007). Attribution theory as a guide for post-crisiscommunication research. Public Relations Review, 33(2), 135–139. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2006.11.016

23. Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2012). The paracrisis: The challenges created by publicly managing crisis prevention. Public Relations Review, 38(3), 408–415. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.04.004

24. Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (Eds.) (2010). The handbook of crisis communication. Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444314885

25. Costa, J. (2004). La imagen de marca. Un fenómeno social. Barcelona: Paidós.

26. Delclós, T. (2011, 28 de abril). Sony tarda seis días en avisar de una colosal brecha de seguridad. El País. Recuperado de https://elpais.com/diario/2011/04/28/sociedad/1303941603_850215.html?rel=mas

27. Douglas, D. (2004). Grounded theory and the ‘and’ in entrepreneurship research. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 2, 59-68.

28. Ehrenfeld, J. M. (2017). WannaCry, cybersecurity and health information technology: a time to act. Journal of Medical Systems, 41, 104. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-017-0752-1https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-017-0752-1

29. Ferguson, T. D., Deephouse, D. L., & Ferguson, W. L. (2000). Do strategic groups differ in reputation? Strategic Management Journal, 21(12), 1195-1214. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200012)21:12<1195::AID-SMJ138>3.0.CO;2-R

30. Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management: A stakeholder approach. Massachusetts: Harpercollins.

31. Gaine-Ross, L. (2003). CEO capital: a guide to building CEO reputation and company success. New Jersey, NY: Wiley & Sons.

32. García-Ponce, D., & Smolak-Lozano, E. (2013). Comunicación de crisis: Compilación y revisión de teorías y taxonomías prácticas desde una perspectiva cualitativa. Vivat Academia, 124, 51-67. doi: https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2013.124.51-67

33. Glaser, B. G. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis: emergence vs. forcing. California, CA: Sociology Press.

34. Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York, NY: Aldine.

35. Gómez-Mompart, J. L., Gutiérrez-Lozano, J. F., & Palau-Sampio, D. (2015). Los periodistas españoles y la pérdida de la calidad de la información: el juicio profesional. Comunicar, 23(45), 143-150. doi: https://doi.org/10.3916/C45-2015-15

36. Grunig, L. A., Grunig, J. E., & Dozier, D. M. (2002). Excellent public relations and effective organizations. A study of communication management in three countries. Mahwah: Laurence Erlbaum Associates.

37. Grunig, J., & Hunt, T. (1984). Dirección de Relaciones Públicas. Madrid: Gestión 2000.

38. Hanggli, R., & Kriesi, H. (2012). Frame construction and frame promotion (strategic framing choices). American Behavioral Scientist, 56(3), 260-278. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211426325

39. Igartua, J. J., Otero, J. A., Muñiz, C., Cheng, L., & Gómez, J. (2007). Efectos cognitivos y afectivos de los encuadres noticiosos de la inmigración. En J. J. Igartua, & C. Muñiz (Eds.), Medios de comunicación, inmigración y sociedad (pp. 197-232). Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca.

40. Jacobs, A., & Helft, M. (2010, 12 de enero). Google, citing attack, threatens to exit China. New York Times. Recuperado de http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/13/world/asia/13beijing.html?ref=technology

41. Kantar MillwardBrown (2017). Brandz Top 100 most valuable global brands 2017. Recuperado de http://brandz.com/admin/uploads/files/BZ_Global_2017_Report.pdf

42. Kim, Y., & Park, H. (2017). Is there still a PR problem online? exploring the effects of different sources and crisis response strategies in online crisis communication via social media. Corporate Reputation Review, 20(1), 76-104. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-017-0016-5

43. Krunal, A. G., & Kumar, P. D. (2017). Survey on ransomware: a new era of cyber attack. International Journal of Computer Applications, 168(3), 38-41. doi: https://doi.org/10.5120/ijca2017914446

44. Locke, K. (2001). Grounded theory 1984-1994. California, CA: Sociology Press.

45. Luecke, R. (2005). Gestión de crisis: Convertirlas en oportunidades. Barcelona: Deusto.

46. Mourle, S., & Patil, M. (2017). A brief study of Wannacry threat: Ransomware attack 2017. International Journal of Advance Research in Computer Science, 8(5), 1938-1940. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.26483/ijarcs.v8i5.4021

47. OJD (2017). Buscador de publicaciones. Promedio de difusión año 2016. Recuperado de https://www.ojd.es/buscador.

48. Olins, W. (2009). El libro de las marcas. Barcelona: Océano.

49. Palacios-Marqués, D., & Devece-Caranana, C. A. (2013). Policies to support Corporate Social Responsibility: The case of Telefonica. Human Resource Management, 52(1), 145-152. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21510

50. Recalde, M., & Gutiérrez-García, E. (2017). Dirección de comunicación y sector de telecomunicaciones: estudio de caso. Doxa Comunicación, 24, 77-101.

51. Recuperado de http://dspace.ceu.es/bitstream/10637/8453/1/Direccion_MonicaRecalde%26ElenaGutierrez_Doxa_2017.pdf

52. RepTrak (2017). RepTrak España 2017. Recuperado de https://www.reputationinstitute.com/CMSPages/GetAzureFile.aspx?path=~\media\media\documents\reptrak_espana_2017.pdf&hash=0f8b030d657a228a8d691f26769a0453ff71d6d604f8f7c92639f610aac0e6e3&ext=.pdf

53. RepTrak (2017a). 2017 Global Reptrak 100. Recuperado de https://www.reputationinstitute.com/CMSPages/GetAzureFile.aspx?path=~\media\media\documents\global_reptrak_2017.pdf&hash=7cde2bdcf25beb53df447672be60dbf7318a9d5e9ef7ace6b7648c23136a1d7c&ext=.pdf

54. Romero-Rodríguez, L. M., Torres-Toukoumidis, A. T., & Pérez-Rodríguez, A. (2017). Gestión comunicacional de crisis: Entre la agenda corporativa y mediática. Estudio de caso Volkswagen. Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas, 7(13), 83-100. doi: https://doi.org/10.5783/RIRP-13-2017-06-83-100

55. Rubin, A. M. (1996). Usos y efectos de los media: una perspectiva uso-gratificación. En B. Jennings, & D. Zillman (Eds.), Los efectos de los medios de comunicación. Investigaciones y teorías (pp. 555-582). Barcelona: Paidós.

56. Sánchez-Revilla, M. A. (2017). Estudio Infoadex de la inversión publicitaria en España 2017. Madrid: Infoadex.

57. Shackelford, S. (2017). Exploring the ‘Shared Responsibility’ of cyber peace: Should Cybersecurity be a human right? Bloomington: Indiana University Kelley School of Business Research, Working Paper nº 17-55. Recuperado de https://ssrn.com/abstract=3005062

58. Shaw, E. (1979). Agenda-setting and mass communication theory. Gazette International Journal for Mass Communication Studies, 25(2), 96-105.

59. Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory, procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage.

60. Telefónica (2016). Elige todo. Recuperado de http://www.eligetodo.com/

61. Telefónica (2017). Incidencia ciberseguridad. Recuperado de https://www.telefonica.com/es/web/sala-de-prensa/detalle-noticia/-/asset_publisher/O34kxJNk5Exu/content/incidencia-ciberseguridad?redirect=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.telefonica.com%2Fes%2Fweb%2Fsala-de-prensa%2Fnoticias

62. Van-der-Meer, T. G. L. A., Verhoeven, P., Beentjes, H. W. J., & Vliegenthart, R. (2017). Communication in times of crisis: The stakeholder relationship under pressure. Public Relations Review, 43(2), 426-440. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.02.005

63. Villafañe, J. (2012). La buena empresa. Propuesta para una teoría de la reputación corporativa. Madrid: Pearson.

64. Villafañe, J. (2008). La gestión profesional de la imagen corporativa. Madrid: Pirámide.

65. Westphalen M. H., & Piñuel, J. L. (1993). La Dirección de Comunicación. Prácticas profesionales. Diccionario técnico. Madrid: Ediciones del Prado.

66. Wolf, M. (1994). Los efectos sociales de los media. Barcelona: Paidós.

67. Woods, C. L. (2016). When more than reputation is at risk: How two hospitals responded to Ebola. Public Relations Review, 42(5), 893-902. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.10.002

68. Woods, D., Agrafiotis, I., & Jason, R. C. (2017). Mapping the coverage of security controls in cyber insurance proposal forms. Journal of Internet Services and Applications, 8(8), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13174-017-0059-y

69. Xifra, J. (2005). Planificación estratégica de las relaciones públicas. Barcelona: Paidós.

AUTHORS

Luis Mañas-Viniegra. Associate professor in the Department of Applied Communication Sciences of the Complutense University of Madrid. Doctor in Audiovisual Communication and Advertising, he has a degree in Journalism and Publicity and Public Relations. He has been a professor at the Carlos III University of Madrid, Rey Juan Carlos University and the University of Valladolid. He is a member of the Complutense research group for Brand Management and Communication Processes, and is currently IP of the Teaching Innovation Project “Visual map of professional orientation for the Degree in Advertising and Public Relations”.

lmanas@ucm.es

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9129-5673

José Ignacio Niño González: Doctor in Advertising and Public Relations from the Complutense University of Madrid, and Master in Business Administration from the Business Institute of Madrid. He is currently Secretary of the Academic Committee of the Doctoral Program in Communication, Audiovisual, Advertising and Public Relations that is taught at the Faculty of Information Sciences (UCM). Currently he is working on two research projects, one of a technological nature linked to the teaching innovation and the other in the field of multi-screen media consumption. He is Deputy Director of the Neuromarketing laboratory “NeurolabCenter” belonging to the Department of Communication Theories and Analysis of the Faculty of Information Sciences (UCM).

josenino@ucm.es

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6940-2399

Luz Martínez Martínez: PhD in Audiovisual Communication from the Complutense University of Madrid. Associate professor in the Degree in Audiovisual Communication of the Rey Juan Carlos University of Madrid and Researcher of the Chair of Communication and Health of the Department of Theories and Analysis of Communication (UCM). She is currently integrated as a researcher in the Neuromarketing laboratory “NeurolabCenter” belonging to the Department of Theories and Analysis of Communication of the Faculty of Information Sciences (UCM). His lines of research are focused on the analysis of the creation and psychosocial and cultural effects of audiovisual discourse in different media, its application in edu-entertainment and the study of its effectiveness through innovative methodologies, neuromarketing.

luz.martinez@urjc.es

Orcid ID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8582-724X