doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2018.47.143-155

RESEARCH

THE ACTIVITY OF SPANISH POLITICAL PARTIES ON FACEBOOK 2014-2018: THE TYRANNY OF THE ALGORITHM

LA ACTIVIDAD DE LOS PARTIDOS POLÍTICOS ESPAÑOLES EN FACEBOOK 2014-2018: LA TIRANÍA DEL ALGORITMO

Xabier Martínez Rolán1 Xabier Rolan. Associate Professor Department of Audiovisual Communication and Publicity (X14). University of Vigo.

1University of Vigo. Spain.

ABSTRACT

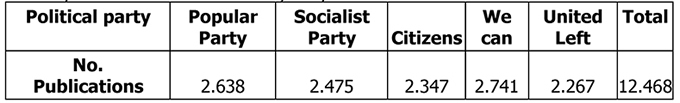

The world’s leading social network, Facebook, is also the scene of the digital political debate. Despite not having the strength of Twitter, its massive implementation makes this platform an ideal channel to reach a mass audience in practically all over the world, in a context of cyber-politics entrenched in Western societies. The research carried out analyses the typology of the publications and interactions received on the Facebook pages of the five main Spanish political parties (Partido Popular, Partido Socialista Obrero Español, Ciudadanos, Podemos and Izquierda Unida) over the years 2014-2018. A descriptive and longitudinal analysis that explores the appropriation of the platform by the different political actors along 12,468 publications, their relationship with the audience and the algorithm that controls the social network.

KEY WORDS: cyber-politics; Facebook; social networks; digital policy; political communication

RESUMEN

La principal red social del mundo, Facebook, también es el escenario del debate político digital. Pese a no tener la fuerza de Twitter, su masiva implantación convierte a esta plataforma en un canal idóneo para llegar a un público de masas en prácticamente todo el mundo, en un contexto de ciberpolítica afianzado en las sociedades occidentales. La investigación llevada a cabo, analiza la tipología de las publicaciones e interacciones recibidas en las páginas de Facebook de los cinco principales partidos políticos españoles (Partido Popular, Partido Socialista Obrero Español, Ciudadanos, Podemos e Izquierda Unida) a lo largo de los años 2014-2018. Un análisis descriptivo y longitudinal que explora la apropiación de la plataforma por parte de los diferentes actores políticos a lo largo de 12.468 publicaciones, su relación con la audiencia y con el algoritmo que controla la red social.

PALABRAS CLAVE: ciberpolítica; Facebook; redes sociales; política digital; comunicación política

Correspondencia: Xabier Martínez Rolán.University of Vigo. Spain. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7631-2292

www. xabier.rolan@uvigo.es

Received: 17/04/2018

Accepted: 31/05/2018

How to cite the article

Martínez Rolan, X. (2018). The activity of Spanish political parties on facebook 2014-2018. The tyranny of the algorithm. [La actividad de los partidos políticos españoles en facebook 2014-2018. La tiranía del algoritmo]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 47, 143-155. doi: http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2018.47.143-155. Recovered from http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/539

1. INTRODUCTION

Facebook leads the digital segment of social networks in Spain. According to the study by IAB Spain (2017) this network is the most mentioned in spontaneous knowledge (99%) and has an average use of 3:20 hours of weekly consumption (1:38 hours, according to We are social & Hootsuite, 2018) . It is, in addition, the main network from which access takes place through Tablet and computer, only surpassed by WhatsApp in mobile devices.

The cocktail analysis (2016) estimates that 88% of Internet users have an account on Facebook. Statista (2016) mentions 24 million as the number of users of this social network is Spain, which is equivalent to almost half of the population.

The strong Facebook impact at a global level - 2,167 million active users (We are social & Hootsuite, 2018) requires more interest on the part of the scientific community, to research its use and evolution from the point of view of mass communication, although it is not as simple as in other platforms.

The strategy of “fenced garden” (Ortiz, 2009; Dans, 2012) of Facebook makes it difficult to extract data to process and analyze them with other types of computer applications.

This philosophy of internal functioning minimizes the possibilities of going abroad, while strengthening the user experience to maximize the time the user stays in the service. Thus, “what happens on Facebook stays on Facebook” has been one of the reasons why studies on this social network proliferate as it happens with other platforms such as Twitter, where its policy of opening and ecosystem of applications has favored the scientific look of the Academy.

However, this type of platform has become a space for public or semi-public conversation where interrelation generates influence (Resina de la Fuente, 2010) and constitutes a new stage of public opinion in a context of 2.0 politics or cyberpolitics.

In this 2.0 policy context, this study analyzes the framework that underlies partisan discourse and is used to construct and interpret the “reality of the political world” (Pan and Kosicki, 2001, p. 40) within the main social network of the world: Facebook.

1.1. Facebook as a platform and its rules of the game

For years, this social network has maintained a neutral discourse as a platform, where users create and publish content. The contents that can be published in this social network are of four types: plain text (now adorned with a background of colors if it does not exceed 130 characters), photographs, videos and links.

It is possible to publish several contents, such as text, link and / or video, but for practical and statistical purposes, only one of the contents determines its typology.

However, the true richness of this platform - like its counterparts - lies in the interactions of the community. Facebook allows different types of interaction in pages (hereinafter, “fanpages”) at various levels in a public way, from the most basic interaction (click) to more elaborate interactions that demand a greater level of proactivity to the user:

I like it: it is the star functionality of Facebook, and allows the community to evaluate what content they like (literally) more. It is situated at the lowest level of interactivity.

Reactions: in October 2015 Facebook introduced reactions in Spain and Ireland, symbols similar to emoji that allow you, with a click, to express feelings about a publication (1). Thus, the classic “I like it” was joined by: I love it, it amuses me, it makes me happy, it astonishes me, it makes me sad and it pisses me off. In January 2017, the reactions spread to everyone, but the reaction “it makes me happy” was lost. The reactions show a higher degree of interest than “I like it” in terms of interactivity.

(1) For more information about each of the reactions, please see the following URL http://www.doubledot.es/blog/como-afectan-al-marketing-las-nuevas-reacciones-de-facebook/

Comments: it allows you to visibly display a comment to a post. In March 2013, the response to the responses was introduced (nested comments), which improved the readability of the conversation about a publication. That same year, it was also allowed to upload other types of content to the comments as images. The comments have a medium level of interactivity, while requiring users to write content to share.

Share the publication: this feature allows you to share a publication on the user’s wall. Over time, this function would be improved, allowing the content to be shared on other managed pages, for example. It supposes the highest level of commitment as long as that shared content will appear on the user’s wall, with the possibility of adding text and / or links that add value to the publication.

From the point of view of social network analytics, public interactions are interesting insofar as they can be quantified and analyzed to check the performance of a Facebook page with respect to its community.

1.2. The algorithm, the holy grail of communication on Facebook

A web service whose average session time exceeds 13 minutes allows you to intuit an important work to improve the user experience and make it stay on the platform as long as possible. The guarantor of this action is the Facebook algorithm, responsible for arranging the publications that each user sees when they connect to the platform, distributing and giving a better position to the contents published on this platform (DeVito, 2017). This algorithm is important for several reasons:

– First, that users consume content passively: they are uploaded to the wall of each user (instead of going to the Facebook page that shows them).

– Secondly, the algorithm performs a task of filtering and showing / hiding content constantly so that the work of the community manager on Facebook tries to please said algorithm to maximize the scope of the publication.

– Third, Facebook does not use a reverse chronological order as it happens in other platforms Practice in disuse after the abandonment by Twitter (Jahr, 2016) or Instagram (Instagram Blog, 2016).

The algorithm of Facebook changes constantly. Almost always they are invaluable changes for the end user, but for the administrators of the pages and managers of online communities, every change can suppose a radical transformation in their content strategy. In the last five years, Facebook has made drastic changes in its algorithm (Farucci, 2018, Wallaroo Media, 2018).

Since June 2014, videos are becoming more and more relevant (Welch, Zhang, 2014) and, although their impact metrics have been questioned (Green, 2015), the changes are driving the video; both traditional formats and live video (Kant, 2016), instigated by the success of direct competitors such as Twitter and Periscope.

In May 2016, pages that published content very frequently suffered a penalty, a fact that affected media or communication channels of public bodies and even political parties.

In general, Facebook has made changes that reduce the organic reach of its publications, either by prioritizing the content of friends and family (September 2016), either because the reactions begin to have more value than the “I like it” (March of 2017). In January 2018, a new update of the algorithm once again placed the natural scope of publications at historical lows (Farucci, 2018).

1.3. Facebook and political communication. State of the art

In the field of cyberpolitics, trying to find the correlation between the “I like it” and the vote to a certain formation has been one of the main motivations of the Academy, although authors such as Barberá and Rivero (2012, 2015)) dismantled this correlation. In the context of Facebook, we have tried to find the relation between the visibility of the “I like it” on the pages and the political bias (Marder et al., 2016) or the Facebook pages have been used to improve political trend algorithms successfully (David et al., 2016).

The relationship between Facebook and political communication captured the worldwide -also academic- interest since the Obama phenomenon in 2008 (Cogburn, Espinoza-Vasquez, 2011, Katz, Barris, Jain, 2013, Gerodimos and Justinussen, 2015), a catalyst from which researchers have focused their efforts on finding out whether social networks really have a direct relationship with political commitment (Carlisle, Patton, 2013). Perhaps motivated by the American elections in 2008, the research efforts have focused on the analysis of candidates (Bronstein, 2013, Steinfeld, 2016, Puentes-Rivera, Rúas-Araújo, Dapena-González, 2017) relegating the activity of the political parties to the background.

In this segment of work, the contributions of Fenoll and Cano-Oron (2017) stand out with their radiography of an election through the citizen look in the comments of Facebook, or the approach of Magin et al. (2017) to the German and Austrian elections.

Thus, the contributions from the university sphere have addressed mainly the perspective of the candidates and, in very specific moments, the electoral elections. Therefore, it is necessary to reflect on the analysis of political communication and consideration of the party as a political subject - more stable than the candidate - as well as the need for longitudinal studies that offer data on the evolution of political communication in these political actors.

In this regard, the purpose of this paper is to analyze the activity of political parties over the past four years to determine if the way in which political information has been distributed - by political parties - and the consumption of such information via the interactions of their virtual communities have changed.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This paper performs a descriptive longitudinal analysis through quantitative analysis, in search of evolutionary patterns throughout the analyzed period, with special interest in the type of content distributed and the generated engagement.

Thus, we find ourselves in a study on big data, where “the related tools invite us to rethink the logic of social research and journalism itself from a broader perspective, where the limits between the fields of study and obtaining of information are further blurred.” (Arcila-Calderón, Barbosa-Caro, Cabezuelo-Lorenzo, 2016, page 630)

Netvizz software was used to capture data, a tool that allowed the retrieval of contents and interactions (Rieder, 2013), and it has been used in numerous studies such as the analysis of hatred speech (Ben-David; Fernández, 2016), or the appropriation of Facebook in electoral contexts (Grömping, 2014, Larsson, 2015, Romero, 2017).

Therefore, Netvizz made it possible to extract the data related to the publications and their typology, as well as their interactions: I like it, comments and number of times shared.

The temporary dimension includes the period that elapses since 2014 (irruption of the Podemos political formation) until the end of 2017; four years of political activity of the five main state political parties in Spain. This period of time justifies the longitudinal study that tries to deepen the changes happening during four years in the “fanpage” of Partido Popular, Partido Socialista Obrero Español, Ciudadanos, Podemos and Izquierda Unida.

Table 1. Political parties and number of analyzed publications. Source: self made

3. RESULTS

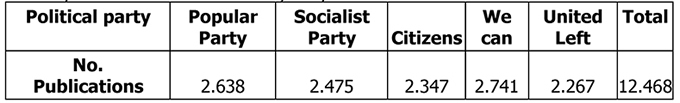

The analysis of the obtained data allows us to verify a slow but continuous increase in the publications of the political parties, although, in general terms, the difference in the number of total publications is not representative between the parties. In 2014, from 450 to 600 annual publications were published, a range that doubled in 2018, reaching from 615 to 745 annual publications.

It is an upward trend in all political parties except the PSOE, which in 2017 had a volume of publications lower than in 2016.

Source: self made

Figure 1. Annual evolution of the volume of publications.

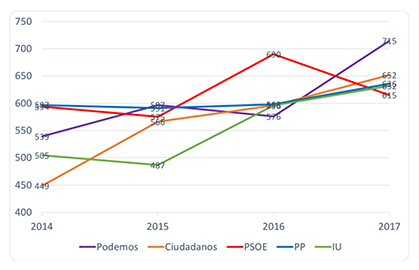

However, the great differences are in the monthly evolution of publications issued by political parties; the analysis of the fluctuations in the publication rate supposes an X-ray of the electoral periods of the political parties.

Source: self made

Figure 2. Monthly evolution of the volume of publications.

Figure 2 shows the major electoral events: European elections in May 2014, National elections in December 2015 and June 2016. In addition to the citations, the volume of publications allows us to find out the importance that political parties grant them: national electoral campaigns practically doubled the number of messages published in the 2014 European elections.

Source: self made

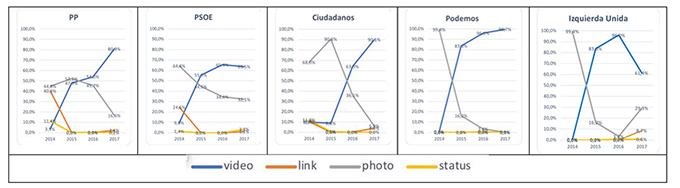

Figure 3. Annual evolution of the type of content.

The annual evolution of the content typology indicates, in all parties, a migration of audiovisual content from photography (the most used in 2014) to video (the most used as of 2015), although the percentage of use differs slightly in the five formations.

A remarkable fact is the strong penetration of video - and very simultaneously on all pages - but the big difference between 2014 and 2017: the video goes from being integrated into 10% of the contents (in the best of cases, with Ciudadanos) to be used from 61% of the time (United Left) to 99% of the time (Podemos)

The publication of links as multimedia content suffers a sharp setback between PP and PSOE, which go from using it one out of four times to practically stop using it. Only in 2017 it suffers a slight rebound on all the pages, but without reaching 10% of the total number of uses.

The presence of publications solely conformed by text is merely testimonial. Only 3% in the best case (PSOE) in 2017, coinciding with the implementation of more graphic and visually attractive status.

In general, similar evolutionary rhythms are perceived, although, at a first glance, surprising is the differentiation between the “old policy” and the “new policy”, because PP and PSOE, on the one hand, and Ciudadanos and Podemos, on the other hand, offer results very similar in terms of the continent of what they post on Facebook.

Source: self made

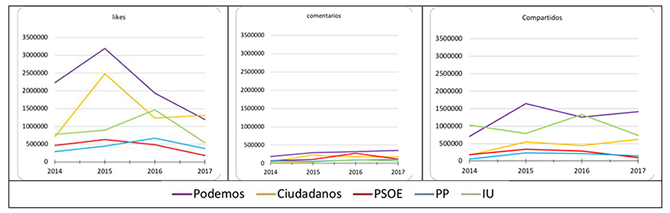

Figure 4. Annual evolution of the interactions (I like it, comments and shares) in the publications.

The relationship of the variables related to the interaction of the community (“I like it”, comments and shared content) shows the different levels of participation and proactivity of the users. The more proactivity the interaction demands, the lower the number of contributions. Thus, the “I like it” (a simple click) are superior to the shared content, and these in turn are more than the comments received by the political parties.

The graphs of evolution of the community of each of the political parties have similarities: the evolution of the number of “I like it” of the publications suffers a severe setback from 2015 with a final volume lower than that perceived in 2014. Especially striking is the case of Podemos, which in 2015 exceeded 300,000 “I like it” and ended 2017 below half of that figure.

In contrast, the volume of comments suffered an increase in all political forces over the years. Podemos and Ciudadanos even doubled the number of comments received over the four years. This could be due to the polarization and extremity of the policy, since users are, in general, more observers and fewer publishers on Facebook (Sun; Rau; Ma, 2014; Hurtubise et al., 2017) and those who take sides are increasingly active (Thompson, 2011).

The volume of comments is significantly lower than the other two variables, although, if we take the initial year and the end as a reference, we can point out a slight increase in the contributions of Facebook users.

In global terms of interaction, Podemos holds the first position in the three analyzed variables, followed by Ciudadanos. For this political formation, 2016 was a bad year in that it showed declines in the variables under study.

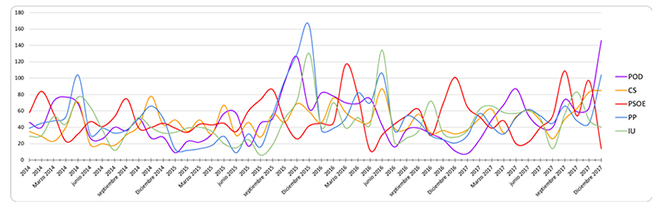

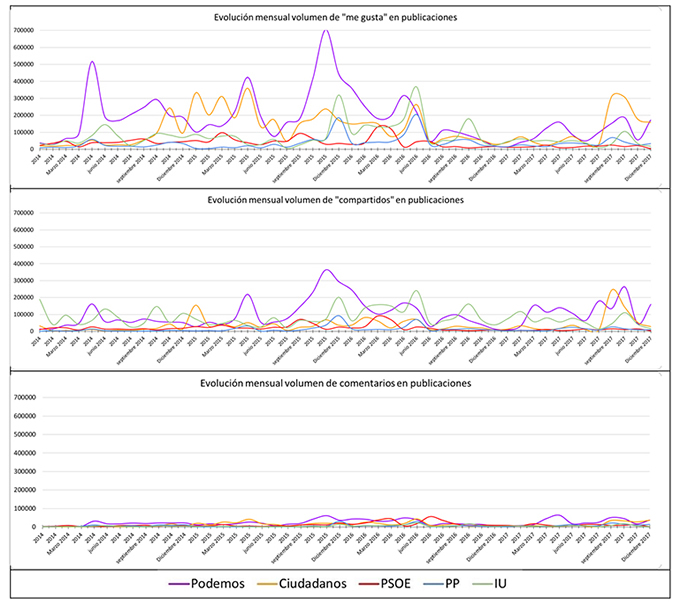

Considering the monthly evolution of the three variables, the results are very interesting.

Source: self made

Figure 5. Monthly evolution of the interactions (I like it, comments and shares) in the publications.

The volume of interactions, whatever their formula, increases on very specific dates coinciding with the electoral dates. To the European dates of 2014 and the national dates of 2015 and 2016, the high volume of interaction in the “fanpage” of citizens at the end of 2017, coinciding with the Catalan political crisis, is noteworthy.

The community is much more participatory with Podemos, Ciudadanos and, punctually, Izquierda Unida.

In this sense, a gap between new and old politics can be pointed out again; the interactions with the new parties are more numerous, especially in terms of “I like it” and shared content, which suggests that this type of formations does not have the decline of traditional parties in social networkses.

4. CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION

According to the publications and interactions with political parties on Facebook throughout the years 2014 - 2017, it is noted that the activity intensifies a lot in the electoral campaign, both on the part of the political parties and on the part of the members of their communities, in tune with the majority studies that radiograph the algid moments of the political communication.

In terms of ownership of the platform, the participation formulas are relatively similar in all political parties: they mostly use the same types of content and adapt to changes in the platform as the algorithm of Facebook corrects parameters such as the scope or the visibility.

All in all, this game of “liquid” adaptation (following the philosophy of Bauman, 2003) does not prevent the contents from being less and less seen by the community. Despite the fact that the volume of publications doubled from 2014 to 2017, the main metric (“I like it”) has decreased in all political parties since 2015, coinciding with the restrictions that Facebook imposes gradually through its algorithm on managed pages.

This way, the personalization of political information on Facebook prefixes criteria that make it possible to have more visibility on a greater number of users (that is, impact) on content criteria than the user community may like.

The levels of interaction are very clear and the difference between each of them is very high, one could even say that it is exponential. The preferred formula for interacting with political parties remains the “I like it”, because it requires much less effort and commitment from the user.

Network-dissemination of contents is not the majority option of interaction. The volume of shared content is low, presumably because it implies a political ascription. In fact, as Martínez-Rolán; Piñeiro-Otero (2017, 868) point out “users only listen to what they want and only network-disseminate those messages with which they agree”.

The volume of comments is exponentially less than that of “I like it”. Something shared by all political groups, although user communities interact more with the “new politics” (Podemos, Ciudadanos and, to a lesser extent, Izquierda Unida) than with traditional parties.

This separation between the classic parties and the new parties appears clearly in the typologies of content, where the volume of publication suggests a close follow-up among direct rivals on the part of the traditional parties (on the one hand) and the disruptive political forces on the national scene (on the other hand).

On Facebook, changes in the consumption of political information are not due to the ways of writing, but to a constant struggle against a complex mathematical formula. The study of these four years of communication of political parties has shown that the cyberpolitics on Facebook runs between a tense relationship among the contents that may interest the audience and the content that may be of interest to the algorithm of Facebook.

REFERENCES

1. Arcila-Calderón, C., Barbosa-Caro, E.; Cabezuelo-Lorenzo, F. (2016). Técnicas big data: análisis de textos a gran escala para la investigación científica y periodística. El Profesional de la Información, 25(4), 623-631.

2. Barberá, P.; Rivero, G. (2012). ¿Un tweet, un voto? Desigualdad en la discusión política en Twitter. I Congreso Internacional en Comunicación Política y Estrategias de Campaña. Recuperado de

3. http://www.alice-comunicacionpolitica.com/files/ponencias/58-F4fffff91581342177169-ponencia-1.pdf

4. Barberá, P.; Rivero, G. (2015). Understanding the Political Representativeness of Twitter Users. Social Science Computer Review, 33(6), 712-729.

5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314558836

6. Bauman, Z. (2003). Modernidad liquida. Madrid: Fondo De Cultura Económica.

7. Ben-David, A.; Fernández, A. M. (2016). Hate Speech and Covert Discrimination on Social Media: Monitoring the Facebook Pages of Extreme-Right Political Parties in Spain. International Journal of Communication, 10, 1167–1193. Recuperado de http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/3697

8. Bode, L. (2012). Facebooking it to the polls: A study in online social networking and political behavior. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 9(4), 352–369. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2012.709045

9. Bronstein, J. (2013). Like me! Analyzing the 2012 presidential candidates’ Facebook pages. Online Information Review, 37(2), 173–192.

10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-01-2013-0002

11. Carlisle, J. E; Patton, R. C. (2013). Is social media changing how we understand political engagement?. An analysis of Facebook and the 2008 presidential election. Political Research Quarterly, 66(4), 883–895.

12. doi: 10.1177/1065912913482758

13. Cogburn, D. L; Espinoza-Vasquez, F. K. (2011). From Networked Nominee to Networked Nation: Examining the Impact of Web 2.0 and Social Media on Political Participation and Civic Engagement in the 2008 Obama Campaign. Journal of Political Marketing, 10(1), 189–213.

14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2011.540224

15. Dans, E. (5 de mayo de 2012). Lo que pasa en Facebook se queda en Facebook. Blog de Enrique Dans. Recuperado de https://www.enriquedans.com/2012/05/lo-que-pasa-en-facebook-se-queda-en-facebook-en-cinco-dias.html

16. David, E.; Zhitomirsky-Geffet, M.; Koppel, M.; Uzan, H. (2016). Utilizing Facebook pages of the political parties to automatically predict the political orientation of Facebook users. Online Information Review, 40(5), 610-623.

17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-09-2015-0308

18. DeVito, M. A. (2017). From editors to algorithms. A values-based approach to understanding story selection in the Facebook news feed. Digital Journalism, 5(6), 753-773. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1178592

19. Farucci, Carlo (2018). “Cambios de Algoritmo de Facebook: Novedades” El Blog de Carlo Farucci, 15 enero. Recuperado de https://carlofarucci.com/cambios-de-algoritmo-de-facebook-2018

20. Fenoll, V.; Cano-Oron, L. (2017). Citizen engagement on Spanish political parties’ Facebook pages: Analysis of the 2015 electoral campaign comments. Communication & Society-Spain, 30(4), 131-147.

21. doi: https://doi.org/10.15581/003.30.3.131-147

22. Gerodimos, R.; Justinussen, J. (2015). Obama´s 2012 Facebook Campaign: Political .Communication in the Age of the Like Button, Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 12(2), 113-132.

23. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2014.982266

24. Green, H. (2 de Agosto, 2015). Theft, Lies, and Facebook Video. Medium. https://medium.com/@hankgreen/theft-lies-and-facebook-video-656b0ffed369

25. Grömping, Max (2014). “Echo Chambers’: Partisan Facebook Groups during

26. the 2014 Thai Election. Asia Pacific Media Educator, 24(1), 39-59.

27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1326365X14539185

28. Hurtubise, K.; Pratte, G.; Rivard, L.; Berbari, J.; Héguy, L.; Camden, C. (2017). Exploring engagement in a virtual community of practice in pediatric rehabilitation: who are non-users, lurkers, and posters? Disability and Rehabilitation. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1416496

29. Iab Spain (2017) Estudio anual de redes sociales 2017. IAB Spain. Recuperado de http://iabspain.es/wp-content/uploads/iab_estudioredessociales_2017_vreducida.pdf

30. Instagram Blog (15 de marzo 2016). See the Moments You Care About First. Instagram Blog. Recuperado de

31. http://blog.instagram.com/post/141107034797/160315-news

32. Jahr, M. (10 de febrero 2016). Never miss important Tweets from people you follow. Twitter blog. Recuperado de

33. https://blog.twitter.com/official/en_us/a/2016/never-miss-important-tweets-from-people-you-follow.html

34. Kant, V. (1 de marzo de 2016). News Feed FYI: Taking into Account Live Video When Ranking Feed. Facebook Newsroom. Recuperado de

35. https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2016/03/news-feed-fyi-taking-into-account-live-video-when-ranking-feed/

36. Katz, J.; Barris, M.; Jain, A. (2013). The social media president: Barack Obama and the politics of digital engagement. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

37. Larsson, Anders O. (2015). Pandering, protesting, engaging. Norwegian party leaders on Facebook during the 2013 ‘Short campaign’. Information, Communication & Society, 18(4), 459-473. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.967269

38. Lévy, P. (2004). Ciberdemocracia. Ensayo sobre filosofía política. Barcelona: UOC.

39. Magin, M.; Podschuweit, N.; Hassler, J.; Russmann, U. (2017). Campaigning in the fourth age of political communication. A multi-method study on the use of Facebook by German and Austrian parties in the 2013 national election campaigns. Information Communication & Society, 20(11), 1698-1719.

40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1254269

41. Marder, B.; Slade, E.; Houghton, D.; Archer-Brown, C. (2016). I like them, but won’t “like” them»: An examination of impression management associated with visible political party affiliation on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 280-287. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.047

42. Martínez-Rolán, X.; Piñeiro-Otero, T. (2017). Lazos invisibles de la comunicación política. Comunidades de partidos políticos en Twitter en unas elecciones municipales. El Profesional de la Información, 26(5), 859-870.

43. doi: https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.08

44. Ortiz, Antonio. (28 de abril de 2009). Facebook del jardín vallado al ecosistema Twitter. Error 500, https://www.error500.net/facebook-jardin-ecosistema-twitter/

45. Pan, Z.; Kosicki, G. M. (2001). Framing as a strategic action in public deliberation. En S. D. Reese, O. H. Gandy, Jr. & A. E. Grant. (Eds), Framing Public Life. Perspectives on Media and Our Understanding of the Social World. (pp. 35-66). N. J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

46. Puentes-Rivera, I.; Rúas-Araújo, J.; Dapena-González B. (2017). Candidatos en Facebook: del texto a la imagen. Análisis de actividad y atención visual. Dígitos: Revista de Comunicación Digital, 18(3), 51-94.

47. Rieder, B. (2013). Studying Facebook via Data Extraction: The Netvizz Application. Proceedings of the 5th Annual ACM Web Science Conference, (pp. 346–355). doi: https://doi.org/10.1145/2464464.2464475

48. Resina de la Fuente, J. (2010). Ciberpolítica, redes sociales y nuevas movilizaciones en España: el impacto digital en los procesos de deliberación y participación ciudadana. Mediaciones Sociales, 7, 143-164.

49. doi: https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_MESO.2010.n7.22284

50. Romero, R. C. (2017). Política Digital: el uso de Facebook en política electoral en Costa Rica (II). Revista de Derecho Electoral, 24(6).

51. Steinfeld, Nili (2016). The F-campaign: a discourse network analysis of party leaders’ campaign statements on Facebook. Israel Affairs, 22(3-4), 743-759.

52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2016.1174385

53. Sweetser, Kaye. D.; Lariscy, Ruthann W. (2008). Candidates make good friends: An analysis of candidates’ uses of Facebook. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 2(3), 175–198.

54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15531180802178687

55. Sun, Na; Rau, Patrick; Ma, Liang (2014). Understanding lurkers in online communities: A literature review. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 110-117. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.022

56. The Cocktail Analysis. (2015). VI Oleada del Observatorio de Redes Sociales. The Cocktail Analysis. Recuperado de http://tcanalysis.com/blog/posts/vii-observatorio-redes-sociales

57. Thompson, R. L. (2011). Radicalization and the Use of Social Media. Journal of Strategic Security, 4(4), 167-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.4.4.8

58. Wallaroo Media. (2018). Facebook News Feed Algorithm History 2018 Update. Wallaroo Media. Recuperado de https://wallaroomedia.com/facebook-newsfeed-algorithm-change-history/#three

59. We are social & Hootsuite. (2018). Global Digital Report 2018. We are social & Hootsuite. Recuperado de https://digitalreport.wearesocial.com/

60. Welch, B.; Zhang, X. (23 de junio 2014). News Feed FYI: Showing Better Videos. Facebook Newsroom. Recuperado de

61. https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2014/06/news-feed-fyi-showing-better-videos/

62. Woolley, J., Limperos, A. M.; Oliver, M. B. (2010). The 2008 Presidential Election, 2.0: A Content Analysis of User-Generated Political Facebook Groups. Mass Communication and Society, 13(5), 631-652.

63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2010.516864

AUTOR

Xabier Martínez Rolán

PhD in Communication from the University of Vigo (2016), developing his professional career in the field of online communication and digital marketing. He is currently Assistant Professor in the department X14 “Audiovisual Communication and Advertising” of the University of Vigo, where he teaches subjects related to mobile applications (degree in audiovisual communication), alternative communication and online marketing (degree in advertising and public relations). His research areas are focused on online communication and mobility, new advertising formats and virtual communities.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7631-2292