10.15198/seeci.2018.47.91-105

RESEARCH

REASON AND EMOTION IN ONLINE CHOICE OF PARTNERS OF CHILEANS

RAZÓN Y EMOCIÓN EN LA SELECCIÓN DE PAREJA ONLINE DE LOS CHILENOS

RAZÃO E EMOÇÃO NA SELEÇÃO DE NAMORADOS ONLINE DOS CHILENOS

Felipe Tello-Navarro1 Doctor in Sociology / Doctor of Information and Communication Sciences. Academic of the career of Social Work and researcher of the Center of Studies and Social Management (CEGES), Autonomous University of Chile.

1Autonomous University of Chile. Chile

ABSTRACT

In line with Critical Theory, dating websites are considered an element that “rationalizes” contemporary sexual-emotional interactions (logic of “hostile worlds”). Through an online survey and interviews, this paper analyzes the partner-choosing criteria of Chilean users in digital dating sites. The objective is to test the hypothesis of “rationalization”. The data show that, despite the variety of criteria for choosing a partner, they must meet two requirements: a) allow observation of the socio-cultural capital of the others; b) and do it without breaking the exclusively emotional imaginariness of the process.

KEY WORDS: Reason; Emotion; Websites dating; Emotional sexual interactions; Choosing criteria; Cultural capital; Romantic imaginariness

RESUMEN

En línea con la Teoría Critica, las páginas de citas (dating websites) son consideradas como un elemento que “racionaliza” las interacciones sexual-emocionales contemporáneas (lógica de los “mundos hostiles”). Por medio de una encuesta online y entrevistas, este trabajo analiza los criterios de elección de pareja de los usuarios chilenos en los sitios de encuentro digital. El objetivo es poner a prueba la hipótesis de la “racionalización”. Los datos muestran que a pesar de la variedad de criterios de elección de pareja, estos deben cumplir dos requisitos: a) permitir observar el capital sociocultural de los otros; b) y hacerlo sin romper el imaginario exclusivamente emocional del proceso.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Razón; Emoción; Páginas de web citas; Interacciones sexual emocionales; Criterios de elección; Capital cultural; Imaginario romántico

RESUME

Em linha com a Teoria Crítica, os de encontros (dating Websites) são consideradas como um elemento que “racionaliza” as interações sexual emocionais contemporâneas (lógica dos “mundos hostis”). Por meio de uma encosta online e entrevistas, este trabalho analisa os critérios da eleição de namorado dos usuários chilenos nos sites de encontro digital. O objetivo é pôr à prova a hipóteses da “racionalização”. Os dados mostram que apesar da eleição de um namorado, este deve cumprir os requisitos: a) permitir observar o capital sócio cultural dos outros; b) faze-lo sem romper o imaginário exclusivamente emocional do processo.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Razão; Emoção; Páginas web de encontros; Interações sexual emocionais; Critérios de eleição; Capital cultural; Imaginário romântico

Correspondence: Felipe Tello Navarro. Autonomous University of Chile. Chile

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5848-6785

felipe.tello@uautonoma.cl

Received: 05/02/2018

Accepted: 14/02/2018

How to cite the article

Tello Navarro, F. (2018). Reason and emotion in Chileans partner’s online selection [Razón y emoción en la selección de pareja online de los chilenos]. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 47, 91-105. doi: http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2018.47.91-105 Recuperado de http://www.seeci.net/revista/index.php/seeci/article/view/521

This paper was carried out thanks to a national doctorate scholarship from the National Science and Technology Corporation (Conicyt), Chile.

1. INTRODUCTION

According to Sergio Costa (2006), sociology has privileged the analyses that oppose the instrumental logic of politics and economics to the “emotional sphere” of sentimental relationships; what sociologist Viviana Zelizer (2009) calls the “theory of hostile worlds” (1). This type of analysis would find its paroxysm in critical theory, particularly in the so-called “Frankfurt School”, one of which central themes is “rationalization” and more specifically the progressive dominance of “instrumental rationality” over all areas of life (Jay, 1989, Honneth, 1990, Basaure, 2011). This type of analysis would be revived at present according to Costa for the relationship between the “third generation” of the School and the cultural studies of the sociologist Eva Illouz.

(1) For the author, the understanding of the “emotional” and the “rational” as separate and isolated spheres, causes the intersection or superposition of them to be understood in terms of “purity” and “contamination”. (Zelizer, 2009).

In her book The Consumption of Romantic Utopia, Illouz (2009) analyzes, during the course of the 20th century, how the market - and particularly the entertainment and leisure industry - builds the cultural practices of “romantic love” by means of which subjects express their emotions. Thus, in advanced modernity, romantic love would manifest itself almost exclusively through consumer practices; what the author calls the “commodification of romance”. In the same way, products designed for love or those that would use a “romantic breath” for their diffusion will emerge during this period, which she catalogs as: the “romanticization of consumption”. The above leads Costa to say (2006) that, to Eva Illouz, there would be a perfect “symbiosis” between market and romantic love, in which both will benefit and before which the author does not observe any possibility of pathology in the sphere of emotions .

To Illouz (2009), what saves “lovers” from the “contamination” of their feelings is the ability of the subjects to appropriate the meanings of the market to establish relationships free of it. As Axel Honneth, one of the most important presenters of the so-called third generation of the Frankfurt School (Basaure, 2008) points out, the subjects have:

the ability to keep their feelings free of strategic considerations of usefulness; rather, they seem to be able to use, with a skill that borders on virtuosity, consumption of goods to protect their relationships, only based on emotional and therefore “pure” affect “(Hartman and Honneth, 2009, p. 417).

It is precisely this “virtuosity” what Illouz observes in the subjects, and the one that differentiates his analysis from the classical studies of Critical Theory. However, to the sociologist, there would exist an evolution of romantic love that can break this virtuosity and “rationalize” and “instrumentalise” love relationships. This transformation is the search for a partner on the Internet, in specialized websites (dating websites); an extended practice in developed countries.

To Eva Illouz (2007), the search for a partner on the Internet would have four relevant consequences: 1) it forces the subjects to focus on themselves and on the other’s ideal; 2) it reverses the traditional relationships of romantic love, while in romantic relationships attraction precedes knowledge, in this case, knowledge of the other precedes attraction; 3) the romantic encounter takes place under the dominion of the liberal ideology of the “choice”, that is to say, a market of couples is constituted; 4) People are placed in an open market that forces each person to compete with the other.

All the above would transform the logic of love in the following way: a) if the romantic imaginariness worked under a logic of “spontaneity”, the search for a partner on the Internet uses a logic of “rational choice”; b) while romantic love is intimately related to sexual attraction, the Internet would function under a de-embodied logic; c) love presupposes disinterestedness, the search for a partner through the Internet implies interest, since each subject needs to increase their own value; d) romantic love is accompanied by the idea of the unique value of the beloved person, while on the Internet the logic is that of abundance, of infinite option, efficiency, rationalization, choice and standardization. This way, it is possible to affirm that, to Eva Illouz, the search for a partner through digital devices produces a process of increasing “rationalization”.

2. OBJECTIVES

The objective of this study is to analyze the partner-choosing criteria of Chilean users of dating websites to determine if they can be called “rational” or “emotional”, in order to affirm or reject the hypothesis that points out that: users of online dating sites establish “rationalized” relationships fostered by the technical device.

In the opinion of this paper, the hypothesis of “rationalization” shows certain “technological determinism”, which leads to observe profound transformations in the “amorous” interactions due to the use of technical devices. Jauréguiberry and Proulx (2011) point out that a deterministic approach consists of evaluating the effects of technical devices on individual and collective behavior. The question posed by this “paradigm”, according to these authors, is to know how the technique influences the sociocultural aspects of living together. Questioning this type of hypothesis is one of the objectives of this paper.

3. METHODOLOGY

So as to describe the rational and / or emotional origin of partner-choosing criteria in the dating pages, two instruments were used. The first one was an online survey. Four techniques were used for its application: a list of email addresses, one of Facebook contacts, a Fanspage and a personal blog. All these alternatives referred to three similar questionnaires: one for email, another for Facebook and another for the personal blog; which were in a server specialized in the construction and application of online surveys (2) .

(2) The specialized page is www.encuestafacil.com

Through email, a link was sent to a database of around three thousand addresses (not all of them confirmed). The email with the request for questionnaire response was sent three times, with a difference of one week between messages, the same method was adopted for the Facebook contact list. The email address of the participants was not required -although this option was available- since they were told that the priority was the confidentiality of the information. A total of 522 questionnaires were answered: 25 by means of the blog, 32 by Facebook and 465 by email.

Regarding the sample, François Singly (2012) points out that, for statistics as well as for sociology, probabilistic type samples are optimum for achieving representativeness. However, it is not always possible to identify a population clearly, since it is sometimes made up of mobile groups with fluid borders, as in the case of the public. A public, the author points out, is always heterogeneous, composed of diverse groups; as for the users of the dating pages, it is possible to find: singles, couples, married, separated; who fall into the following kinds of users: frequent, sporadic, who have visited the dating pages only once; who have established (or not) a relationship with another person; on the other hand, the relationship that can be virtual or face to face; and which can adopt different names: “love affair”, “sexual relationship”, “friends with advantage”, “couple relationship”.

This way, to the diversity of the act that turns a person into a user, we must add the heterogeneity of their social, economic and cultural characteristics. That is why the type of selected sampling was the so-called “spontaneous” or a posteriori. The “spontaneous” sample, that is, the one composed of those who voluntarily answered the questionnaire, or later (Henríquez, 2002), is not representative in a statistical sense, but it gives a good profile of the audience, an image stylized by the accentuation of relevant characteristics (De Singly, 2012).

The analysis of the data obtained by the application of this instrument was descriptive, as defined by Hernández et al. (2006). In addition, inferential analysis techniques were not used, since it is not possible to extrapolate the results to a larger population (see Annex 2). This way, the analysis of the numerical data privileged the percentages and absolute frequencies; it will be specified when some or others were used in the graphs we made.

The second method we used was the interview, both in its online and face-to-face formats. Regarding the latter, there is little to say, the interview (face to face) is a completely accepted and practically standardized method of social research (Kaufmann, 2013, Opdenakker, 2006, Ardèvol et al., 2003, Bampton and Cowton, 2002, Baeza, 2002). Baeza (2002), points out that the interview always involves a communicative contract between at least two people -an interviewer and at least one interviewee-. It always involves some degree of trust and respect for certain standards: the turns for speaking and mutual listening. The constitution of this contract, says Ardèvol et al. (2003), is more difficult in the case of online interviews. The foregoing is due to the distrust in the interaction produced by “no physical presence” and the difficulty of coordinating certain speech acts. This is why, perhaps, the sociologist Jean-Claude Kauffman (2013) questions the usefulness of this technique for Internet research.

In this study, we conducted twenty-six unstructured interviews: twelve with men and fourteen with women. The interviewees had an age range ranging from 20 years to more than 60. The interviews were conducted by different offline and online means. The logic of sampling was the principle of saturation of information (Baeza, 2002). The decision to conduct unstructured interviews arose after a first application of the instrument. In this pilot application, two interviews were conducted with a semi-structured guideline; however, already in the realization of the interviews it was possible to realize that the guideline did not capture the particularities of the users’ experience. That is why we chose to conduct unstructured interviews, although in the same way, and in order to achieve a certain disposition in the answers, the following order was followed: opinion and objectives of entrance to the web pages; experience and use of the web pages: online interactions; the transition from online to offline; and face-to-face relationships.

Regarding the method of analysis of the interviews, it followed the following steps. All material was reduced to written text. In this sense, both recorded and textual interviews built two corpuses -one for men and one for women-. Here the differences in means and formats disappeared and all interviews, regardless of whether they were conducted face to face or by any electronic means, had the same treatment. The interviews that were carried out through textual media maintained their literality and were not intervened; therefore, they preserve their orthographic and grammatical errors; this in order to preserve their meaning to the maximum (Kauffman, 2013).

After having all the material in a homogeneous format, we continued with a new reading, this time to look for coding the raw material with more general concepts. In this sense, an inductive procedure was made close to what the Grounded Theory does, although founded in the work of bibliographic review and the theoretical discussion carried out previously (Kauffman, 2013). After this first coding was carried out, a new reading of the interview material was performed in order to extract the most representative fragments -phrases or paragraphs- and introduce them into the analysis mesh. Finally, deductive work was carried out, where the elaborated concepts were reordered and introduced in more general notions or themes. It is on the analysis mesh that the interpretation of the data was made. On the other hand, the interpretation was made at the moment of writing the corpus of this study. As a mechanism to control the interpretation process, careful reading of the collected data and their comparison was carried out, both with the quantitative data and with the theoretical work.

4. PARTNER-CHOOSING CRITERIA

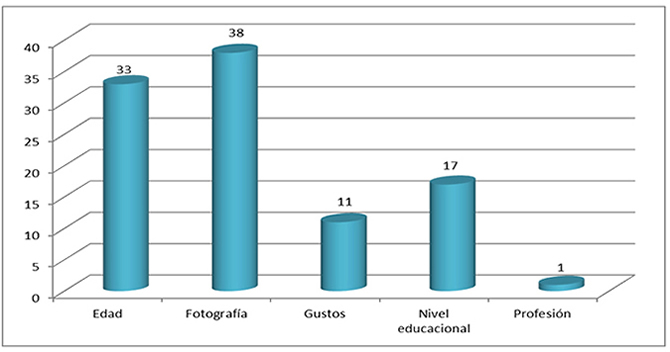

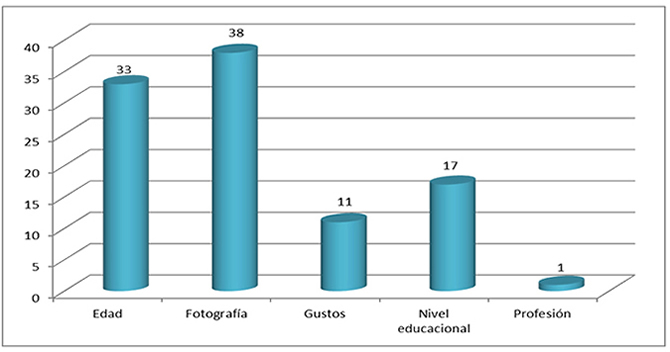

Next, the most relevant criteria for the users of the dating web pages are presented when evaluating a possible future partner. Thus, Graph 1 shows first thing drawing the attention of users when looking at the profile of another in the dating pages. Graph 2 analyzes the same results divided by gender.

Graph 1: What is the first thing you look at set when visiting the profile of another person? (absolute frequencies)

Graph 2: What is the first thing you look at when visiting the profile of another person?

It is possible to observe in the previous graphs that the first thing that attracts the attention of users of the dating pages is the «photograph»; the above for both men and women (Graph 2). The interviewed users also give an account of that.

“So, obviously, at the beginning, the first step you take is that she is a girl who attracts you, or who looks attractive in the picture ...” (Man 30-39 years).

«Starting with the photo, if positive ‹, the photo is the easiest way to know if a person is attractive or not ...» (Woman 20-29 years).

«I think that everything goes through the eyes ... because when you say I like him, it›s because you liked something, that is, if you do not know anything, and you like what you saw in the picture, we start there ...» ( Woman 30-39 years).

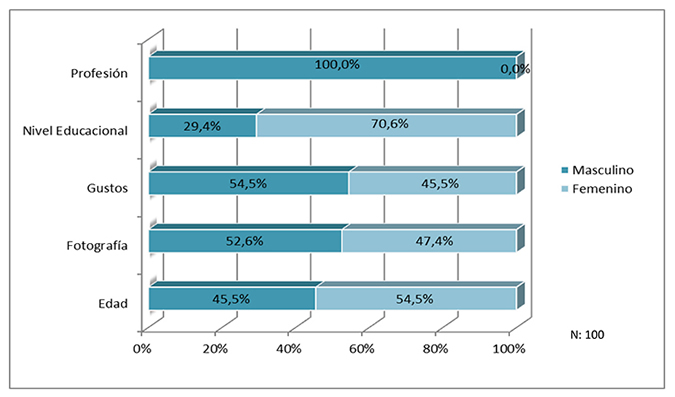

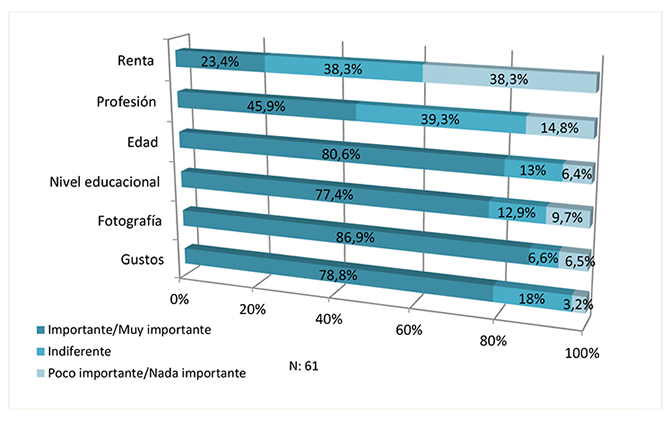

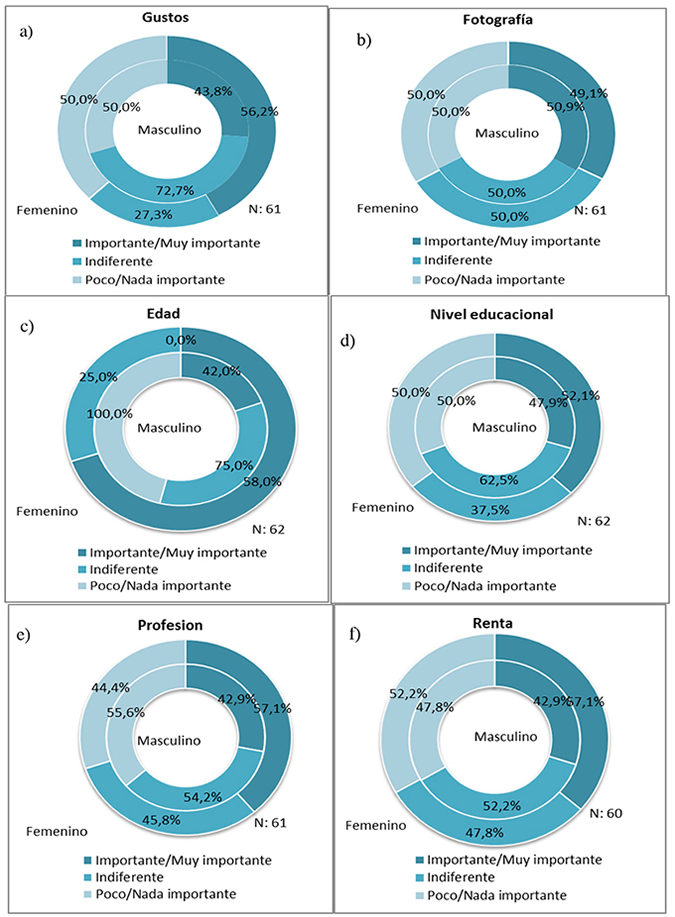

As they affirm, it is through the photo that they perceive if others are attractive or not. The photo thus becomes the body of the other on the web (Tello, 2016). Graph 3, on the other hand, indicates the assessment users make of certain characteristics of the others. Among them are: “age”, “photo”, “educational level”, “tastes”, “profession” and “income”. Internet users were asked to classify these attributes into the following categories: “very important”, “important”, “indifferent”, “scarcely important”, “unimportant”. Graph 4 shows the same results as the previous graph divided by gender. In order to make the presentation of the results more intelligible, the “important / very important” and “scarcely important / unimportant” categories were grouped in Graph 3 and Graph 4.

Graph 3: How relevant do you consider these attributes in the profile of another person?

Graph 4: How relevant do you consider these attributes in another person’s profile?

Graph 3 shows that photo is the most important attribute in the profile of the other people for Chilean users of dating pages. In turn, Graph 4 shows that this assessment is similar for men and for women. Thus, the belief of common sense -very widespread in Chile- that indicates that men value appearance more with respect to women does not seem to be proven in this case. Regarding the assessment of the image made by the users, they are aware that appraisal through a photo can be something stereotyped and even prejudiced. However, they claim that in the dating pages there is no other way to judge the other.

“Of course, one ... at first glance ... a person enters through sight, despite everything we are a society with several prejudices, clearly, sometimes things enter through sight ...” (Man 20-29 years).

The above reinforces Eva Illouz’s (2012) assertion that “sexual attractiveness” is one of the most relevant criteria when establishing couple relationships in contemporary society, and in the dating pages the way to capture that attraction is the photo.

The other relevant criterion to consider when users access the profile of another user is “age” (see Graphs 3 and 4). Despite the popular saying, “love has no age”, in online dating sites it is a relevant criterion (Graph 3), perhaps even more than in the offline world. The above results from the possibility that these websites offer to make intergenerational dates. While, off the Internet, the specialized sites in romantic encounters: bars, restaurants, cafes, discos, are (almost always) differentiated by age-group targets: places for teenagers, young adults, adults, seniors; the Chilean online dating sites are characterized by being generalists (Lardellier, 2014). This makes it possible for the different generations of singles to meet in the same place. Thus, for example, the users of the dating pages claimed to receive numberless virtual messages from men of different ages. Some of them “very minor” and others “very old”. This explains, perhaps, because the attribute “age” is more relevant to females than to males (Graph 4d). The importance of age as a criterion for choosing a partner can be seen in the following stories.

«... and after that, like you can put filters, and like you do not want older or younger people [...]. As I do not want to talk to all these people, people much older and / or much younger than me, as well as 20 years »(Woman 20-29 years).

“For example, the 36-year-old I thought, if I fucking, do I talk to him or not? And then I talked to him and what the ...? and he answered to me ‘... And since he was a historian, he seemed interesting to me and I said, I ... I’ll talk to him. There, the issue of age was not a problem, for example ... »(Woman 20-29 years old).

«Younger, no ... one year younger is already bad, buddy (laughs) because men are more immature ‹...» (Woman 20-29 years).

A type of interaction not uncommon among the interviewed users is that established between young men and older women. It is not possible to affirm that this phenomenon is typical of the Internet but that this medium facilitates this type of interaction. Several interviewees aged 30, 40, 50 years and older say they receive a number of messages from men younger than them.

Many of these messages are rejected by these women arguing that their issuers could be their children; others, on the other hand, have no problem receiving these messages and interacting with their virtual suitors; and a last group of them have even established sexual-emotional relationships with them. The interviewed men, on their part, also report this phenomenon. While some of them make a complaint about the fact that women on dating pages are looking for younger men, as the one who points out:

«In general, I see women looking for younger men. Funny thing, and I already at 53 years old and I am already a little out of much of the «market» or female segment of my interest, although I keep very well »(Man 50-59 years).

Others, on the other hand, have no problem recognizing that they are looking for older women, especially when they are attractive. What in the Internet culture is called MILF (3).

(3) Mom I’d like to fuck (MILF) in Latin America would translate as: “Mom who would take me” https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/MILF

«... of course I was looking for rich ladies, why would I go looking for fatty ones? If they do not have a shine, then, of course, I started to go out with a lot of women like that ... »(Man 40-49 years old).

«A couple of years younger and up to 10 years older than me, thin [...] That›s the first filter. The rules is: not to weigh more than I hahaha ... » (Man 30-39 years).

The other relevant criterion in a descending order is the “educational level” (Graph 1). Graph 2 shows that it is mainly women who value this characteristic to a greater extent. They represent 70.6% of those who selected “educational level” when asked what is the first thing that catches your attention when you visit the profile of another user? versus 29.4% that men represent (Graph 2). The above would come to corroborate that women, as Eva Illouz (2012) points out, use a matrimonial strategy of endogamy or hypergamy, that is, they look for a partner with the same or higher educational level than they have.

Graph 3 shows that, with respect to the “educational level”, the category “important / very important” represents 77.4% of the selected options; while «indifferent» represents 12, 9% and « scarcely important / unimportant» represents only 9.7% for the same attribute. Graph 4e shows that, in the category “important / very important”, men and women have almost the same percentage: 52, 1% men versus 47.9 women. The above shows that the educational level is a transversal and fully validated criterion for choosing a partner (Illouz, 2009)

The next criterion selected in a descending order was “tastes” (Graph 1). Graph 2 shows that this criterion is slightly more important to men in the first approach to another (54.5%) than to women (45.5%). Graph 3 shows that “tastes” is considered “important / very important” in 78.8% and “scarcely important / unimportant” only in 3.2% of the occasions. This agrees with what was posed by Illouz (2012), who affirms that, in addition to the physical aspect (sensual capital), the other key factor to generate attraction in people is “psychological affinity”. This aspect is manifested in the combination of tastes, hobbies, interests and similar expectations among other elements. Thus, in dating pages, tastes are a fundamental criterion when selecting a user’s profile. Graph 4 shows that it is women who give the highest positive value to this attribute: 56.3% for the “important / very important” category, versus 43.8% of men for the same category.

One of the last chosen attributes was “profession”. It was selected only once (Graph 1). Graph 3 shows which profession was considered “important / very important” only in 45.9% of the time, well below the other analyzed attributes. Graph 4f shows that it is women who give greater importance to this attribute: 57.1% consider it “important / very important”, against 42.9% of men who classify it in this same category. Of course, given the “spontaneous” sampling, this cannot be extrapolated except to the people who answered this survey.

Finally, the category “income” is not even mentioned to the question: What is the first thing that attracts your attention when looking at the profile of another person? And which option was part of the questionnaire to complete. The low valuation of this criterion is shown in Graph 3, where “income” is qualified as “important / very important” only in 23, 4% of the cases, while in 38.3% it is qualified as “indifferent” and in the same percentage it is qualified as “scarcely important / unimportant”. This way, as in face-to-face sexual-emotional relationships (Illouz, 2009), in the dating pages, income is not an attribute to be considered by people when establishing a possible love relationship. This way, the theory of “hostile worlds” (Zelizer, 2009) continues to be useful in discursive terms to justify the criteria for choosing a partner in the online world.

However, it is necessary to ask: How is it that income is not valued by the users of the dating pages as a partner-choosing criterion, while the educational level is valued, if both lead to determine the socioeconomic level of the persons and their social stratum? This question is especially relevant in Chile, where the “universalization” of access to higher education is recent and is highly unequal in terms of socioeconomic strata (Scheele, 2015). The answer is that “income” and “educational level” lead to divergent conceptions of the process of choosing a partner in the modern romantic imaginariness.

While the income of the people is seen as a materialistic, utilitarian and cold criterion of choice of partner, totally away from the feelings (logic of the “hostile worlds”), the educational level is associated with individual attributes that are away from a utilitarian logic and close to personality characteristics, such as: personal effort, upgrading, dedication, appreciation for knowledge and refinement of tastes, among others. All characteristics highly valued in a future partner (Illouz, 2012). Since tastes and interests are one of the key elements when choosing a possible future partner, the educational level will be a crucial element to generate “affinities” as shown by the following stories:

«... I pay attention to university education, mainly because ... technical, they can be electricians, in fact they have been ... and what am I going to talk about with these people? Am I going to talk about ethics? Do you notice? »(Woman 50-59 years).

« I have suddenly seen women that are exquisite, exquisite, exquisite, exquisite, but they put high school, did I make myself understood? And I work at home, ah no! »(Man 40-49 years).

Other interviewees, on the other hand, will not be so direct but, in the same way, they are discriminating because of the educational level of their interlocutor.

«Yes ... I must admit that it is not so, so relevant the subject of studies, but it can be in terms of what you do and what you like, what is relevant to you. I saw if people liked to read or go out, or do something, and that started to interest me and that led me to send a message, it was not a visual matter ... pretty ... not at all ... » (Man 40-49 years) .

Eva Illouz (2009; 2012) points out that our culture approves rational selection based on the moral qualities or character of people, not so with other characteristics that are observed as instrumentalized, for example, economic resources. This way, the educational level will allow a double game. On the one hand, it allows people to choose a future partner based on the supposed “individual” characteristics of the latter, such as their values, tastes and interests, assuming as the romantic imaginariness does centuries ago the “unique” and “unrepeatable” of the beloved person (Marquet, 2009); and in turn, it allows individuals to select someone socially appropriate, that is, someone socially, culturally and economically similar to themselves.

A criterion that is typical of the interactions within the dating pages, which Illouz (2007) characterizes as “textualized”, is “spelling”. The references that users made to spelling are almost unanimous when they were consulted by what they did not like about their virtual interlocutor. That which, using a colloquial expression in Chile, “killed the passions”. Below, some of the expressions stated by the interviewees.

«I also understand inside the Internet that a» K «is typed instead of a» Q «, I do not interpret it as bad writing, but when I write something formal, I write it as it should be, with its accents, comma, with everything, but if I have to do it short I use the abbreviations, but even when they write «hace» (do) as: «ASE» you screwed me up «. Why?, I do not know, but I did not like it »(Man 30-39 years).

«... because suddenly they are full of spelling mistakes, although the Iphone marks something else, but when you see that they write badly, that is killing passions ...» (Woman 40-49 years).

«Yes ... as they wrote, the spelling, the way of expressing themselves, the words they wrote, and if not totally discarded. They were not all, but sometimes I stopped answering or I simply told them that I was looking for something else «(Woman 20-29 years old).

The relevance of spelling is such that it can even overcome the “physical” attraction to another person.

“... the first thing that catches your attention is that she is pretty, and then as I wrote ... she could be very beautiful, but the woman wrote very bad then no way ‘” (Man 30-39 years).

«... and as she writes ‹, because goddam, that thing is super important, and the misspellings there are passion killers, I walked with, I dated women of the Dating who I have liked ‹, so seriously I have liked them … Yes, I have dated them, I have gone out with them, I have made love, I have taken them to my place, and I have tried to convince myself, I have tried to convince myself all the time, that I am going to stay with that woman, because they have been like I want them, and misspelling have fucked it up, when I chat with them like that and they start to write like that, and I see misspellings, but there are things that are aberrant, and it fucks me up, goddam, because I say goddam if it is like that, what’s new? ‹see what I mean or not? How can you? If there is, I do not know, they are things ‹of one also See what I mean or not?, it really would not have to matter, but to ‹me it does matter› (Man 40-49 years).

Spelling in the dating pages specifies the cultural capital of the people. According to Bourdieu (1974), cultural capital has a high degree of “cover-up” and is thus predisposed to function as symbolic capital, that is, unknown and recognized, exerting an effect of (ignorance) knowledge, especially in the marriage market. Thus, spelling, as well as the educational level, has the advantage of not bearing a utilitarian and / or classist halo. The above does not mean that some users do not perceive the class substrate of this attribute.

«No, if the person has bad spelling, if he is flaite ‹no, not immediately not ... bad writing not ... that they are talking like that, I do not know what ... no. There I do not want to talk anymore and period and no more and I do not want them to talk to me anymore ... » (Woman 50-59 years).

The notion “flaite” in Chile refers -in one of its meanings of use- to people from popular sectors who have socially undue and / or even criminal behavior (Rojas 2015). Although some users are more reflective about spelling as a criterion for evaluating the other and the class substrate the other has, they do not escape an individualistic explanation of the phenomenon.

« ... I did not like [bad spelling] ... I think that, on my mind, maybe only I see it as ... I think we all tend to read, or to learn basic things you do not need great schooling, I›m not from a great school, I lived in a town before, that is, now I live here, I grew up in a town, in a basic school, and then in a high school all flaite ‹, but I learned to write well see what I mean?, to express myself well; I learned the things that a person had to learn, to personally feel whole. So I say that if someone does not know how to write basic things, it›s because maybe ... they will have low morale, I do not know ... I do not understand those things very much, but personally, that provokes me [...], always lower-class people have low morale, in that sense because I am of low social class see what I mean›?, but I did not have the morals so low as to learn to write, to learn to speak, I wanted to be the same ... always write badly like wanting just a little ... not respecting oneself » (Man 30- 39 years)

As can be seen, the interviewee, based on his personal experience, associates the impossibility of overcoming certain difficulties with a low morale of the popular classes, which can be overcome by means of “personal effort”. The logic of personal effort, merit and individual rewards is part of the neoliberal project imposed in Chile in the eighties of the last century, which, among other factors, enthrones the idea of an actor strongly responsible for his destiny (Araujo and Martucelli, 2013).

5. DISCUSSION

The analysis of the results shows that Chilean users of dating pages use criteria that are both rational and emotional to choose a partner. Thus, the presence of “criteria to evaluate” the other does not mean that users of these websites are rational agents, who weigh each of their options under discrete criteria that allow them to choose the best alternative available to achieve their goals. Even less that these users use a “utilitarian” logic to establish a relationship. On the contrary, the absence of strictly economic criteria such as “income” is an expression that Chilean users reject this type of attribute as a valid parameter to establish relationships. Thus, unlike what was pointed out by Eva Illouz (2007), sexual-emotional interactions on the Internet are not necessarily rationalized.

On the other hand, the rejection of “utilitarian” criteria is not a manifestation that the users of the dating pages establish only emotional relationships, although feelings are part of these interactions (Tello, 2017). The importance of tastes, educational level and spelling dismisses this type of interpretation. Unlike what some authors point out (Hartman and Honneth, 2009), the ability of subjects to protect their relationships from instrumental calculation does not mean that they establish “pure” relationships, in the sense of exclusively emotional. Sociologist Viviana Zelizer (2009) shows, for the offline world, that every couple relationship combines both strategic calculation and therefore interest as well as emotion.

This way, Chilean users of the dating pages will look for other similarities of tastes, interests and life expectancies that make a future relationship compatible. In order to find that “compatibility”, the selection criteria must meet two requirements: 1) Make it possible to observe the sociocultural and therefore economic capital of the other, and, 2) Do it “concealing” (Bourdieu, 1974), what it has of interest. Thus, the criteria for the choice of a partner make it possible to combine two of the central logics of partner formation in contemporary society: sociocultural (Lardellier, 2004; 2012) and therefore economic (Illouz, 2009; 2012) endogamy; and the exclusively emotional imaginariness of the process (Marquet, 2009).

6. CONCLUSION

In summary, it is possible to establish that the analysis of the partner-choosing criteria in the dating pages allows us to affirm that there is no such “rationalization” as some authors point out. People, as in the offline world, combine emotional and rational elements in their digital relationships and are able to keep them free of “strategic calculation”. The attribution of “distorting” capabilities to technical devices such as dating pages is a reissue of the logic of the hostile worlds typical of Critical Theory. This type of paradigm qualifies the emotional and the rational as sealed and therefore “pure” domains that can be “contaminated” by the introduction of external elements. This logic is updated today through a certain “technical determinism” that prevents us from observing the ability of subjects to adapt, appropriate and use technology in different ways.

REFERENCES

1. Araujo K, Martuccelli D (2013). Individu et néoliberalisme: Reflexions a partir de l’experience chilienne. Problèmes d’Amériques latine, 88(1) 125-143. doi: 10.3917/pal.088.0123

2. Baeza MA (2002). De las metodologías cualitativas en la investigación científico-social. Diseño y uso de instrumentos en la producción de sentido. Universidad de Concepción.

3. Bampton R, Cowton C (2002). The e-interview. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3. Recuperado de http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs020295.

4. Basaure M (2008). Dialéctica de la Ilustración entre la filosofía y literatura Axel Honneth en entrevista con Mauro Basaure. Persona y Sociedad, XXII(1):59-74.

5. Basaure M (2010). Continuity through rupture with the Frankfurt School: Axel Honneth’s theory of recognition. En Delanty G, Turner SP (eds.): Handbook of Contemporary Social and Political Theory (pp. 99-109). London: Routledge.

6. Bourdieu P (1979). Los tres estados del capital cultural. Sociologica, n°5, 11-17. Recuperado de http://www.sociologicamexico.azc.uam.mx/index.php/Sociologica/article/view/1043/1015

7. Costa S (2006). ¿Amores fáciles? Romanticismo y consumo en la modernidad tardía. Revista Mexicana de Sociología 68(4):761-782. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/321/32112605005.pdf

8. De Singly F (2012). Le questionnaire. Paris: Armand Colin.

9. Hartman M, Honneth A (2009). Paradojas del capitalismo. In A. Honneth (Ed.), Crítica del agravio moral. Patologías de la sociedad contemporánea. Mexico DF: Fondo de cultura economica.

10. Hernández R, Fernández C, Baptista P (2006). Metodología de la investigación . Mexico DF: McHill.

11. Honneth A (1990). Teoría crítica. En Giddens A, Jonathan HT (eds.): La teoría social hoy (pp. 445-488). Madrid: Alianza.

12. Illouz E (2007a). Intimidades congeladas. Las emociones en el capitalismo. Buenos Aires: Katz.

13. Illouz E (2007b). El consumo de la utopía romántica. El amor y las contradicciones culturales del capitalismo. Buenos Aires: Katz.

14. Illouz E (2007c). ¿Por qué duele el amor? Buenos aires: Katz.

15. Jauréguiberry F, Proulx S (2011). Usages et enjeux des technologies de communication. Toulouse: Érès.

16. Jay M (1989). La imaginación dialéctica. Una historia de la escuela Frankfurt. Madrid: Taurus.

17. Kaufmann JC (2013). L’Entretien compréhensif. París: Armand Colin.

18. Lardellier P (2004). Le Coeur NET. Célibat et amours sur la web. París: Belin.

19. Lardellier P (2012). Les réseaux du coeur. Sexe, amour et seduction sur Internet. Paris: Francois Bourin Editeur.

20. Lardellier P (2014). “El liberalismo a la conquista del amor. Algunas contestaciones y reflexiones sobre el consumo sentimental y sexual de masa en la era de internet”. Revista de Sociología Universidad de Chile, 29, 77-87.

21. Marquet J (2009). l’Amour romantique a´l´epreuve de internet. Dialogue, 186(4):11-23. DOI: 10.3917/dia.186.0011.

22. Opdenakker R (2006). Advantages and disvantages of four interview techniques. Forum: Qualitative Socia Recherch, Vol. 7. Recuperado de http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0604118.

23. Rojas D (2015). Flaite: Algunos aportes epistemológicos. Alpha, 193-200. doi: 10.4067/S0718-22012015000100015

24. Scheele J (2015). Logros y desafíos pendientes para la inclusión y retención en la educación superior. Informes para la política educativa (Vol. N°7). Santiago: Universidad Diego Portales.

25. Tello F (2016). El cuerpo en Internet. La fotografía en las páginas web de citas utilizadas por chilenos. Revista Faro, 2(24):62-84. http://www.revistafaro.cl/index.php/Faro/article/view/453/455

26. Tello F (2017). Emociones de computador. La experiencia sentimental de los saruiros chilenos de las paginas de citas. Revista Caracteres, 6(2):79-106. Recuperado de http://revistacaracteres.net/revista/vol6n2noviembre2017/emociones/

27. Zelizer V (2009). La negociación de la intimidad. Buenos Aires: Fondo de cultura económica.

AUTHOR

Felipe Tello Navarro

Doctor in Sociology / Doctor of Information and Communication Sciences. Academic of the career of Social Work and researcher of the Center of Studies and Social Management (CEGES), Autonomous University of Chile

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5848-6785