doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2016.40.69-103

RESEARCH

TELEVISION AND METACOGNITION: MINORS EXPOSED TO CELEBRITIES

TELEVISIÓN Y METACOGNICIÓN: LOS MENORES ANTE LAS CELEBRIDADES

Javier Fiz-Pérez1

Gabriele Giorgi1

Blanca Sánchez-Martínez2

1European University of Rome. Italy

2Complutense University of Madrid. Spain

ABSTRACT

Control of television for minors is justified, as evidenced in this article, in terms of the importance of celebrities and fictional characters for their evolutionary development and self-esteem levels and metacognition. As we know, these celebrities and fictional characters represent conduct models to follow, especially preteens, who may adopt them in the time phase for cognitive development in which parents are de-idealized to idealize celebrities that children choose as their conduct models in their continuous search of their own abilities and skills. On television, the values ??common to all cultures (power, achievement, stimulation, hedonism, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity and security) are represented by the characters and celebrities appearing on their spaces, indicating to the preteen those values that give social prestige and those that absolutely do it, minors being the ones who must decide on their own account. Throughout this piece of research, we demonstrate how preteens interact with their favorite celebrities and what the role of those characters in their daily lives is.

KEY WORDS: Television, Children, Celebrity, Preadolescence, Metacognition, Esteem, Securities

RESUMEN

El control de la televisión para menores está justificado en cuanto a, como se evidencia en este artículo, la importancia que las celebridades y personajes de ficción tienen en su desarrollo evolutivo y en sus niveles de autoestima y de metacognición. Como es sabido, estas celebridades y personajes de ficción representan modelos de conducta a seguir que, especialmente los preadolescentes, pueden llegar a adoptar en el momento en que se produce la fase de desarrollo cognitivo en la que se des-idealiza a los padres para idealizar al propio sujeto elegido como modelo a imitar, en la continua búsqueda de sus propias habilidades y competencias. En la televisión, los valores comunes a todas las culturas (poder, logro, estimulación, hedonismo, autodirección, universalismo, benevolencia, tradición, conformidad y seguridad), están representados por los personajes y celebridades que en sus espacios aparecen, indicando al preadolescente aquellos valores que otorgan prestigio social y aquellos que en absoluto lo hacen, siendo estos, los menores, los que deberán decidir cuáles representan los suyos propios. A lo largo de esta investigación se demuestra cómo interactúan los preadolescentes con sus celebridades favoritas y cuál es el rol de esos personajes en su día a día.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Televisión, Menores, Celebridad, Preadolescencia, Metacognición, Autoestima, Valores

Recibido: 23/01/2016

Aceptado: 17/04/2016

Publicado: 15/07/2016

Correspondence: Javier Fiz-Pérez

javier.fizperez@unier.it

Gabriele Giorgi

prof.gabriele.giorgi@gmail.com

Blanca Sánchez-Martínez

blancsan@ucm.es

1.INTRODUCTION

1.1 How the need to control television for children arises

Three million Italian children watch cartoons at least three hours a day. Italian TV chains broadcast 4,790 hours of cartoons per year, equivalent to 199 days of uninterrupted transmission.

Children are exposed to television from birth: the TV set remains on an average of ten hours a day and accompanies the development of domestic life, becoming an integral part of the family atmosphere. Even babies listen to television. In this context, it is necessary to question the quality of something that represents such an important part of everyday experience of minors: if the TV is a simple contraption or an exceptional teacher, a boob tube or a magic window.

The views in this regard are always different; however, it can be summarized in two dominant attitudes: the first is that the power of television is harmful, especially against a non-adult audience with a still incomplete knowledge of the world. In fact, children do not have well-defined interpretive patterns of reality, and they also lack experience and cultural background allowing them to distinguish the subtleties of the messages broadcasted by television. The criticism is directed mainly to behavioral models offered on television. At a very early age, children develop their sense of identity with their interpretive schemes of the world, and TV provides them with countless models with which to identify. Supporters of this apocalyptic television viewing point to the fact that television provides easy play behaviors that show how to play and this becomes a problem when the behavior shown on video is dangerous and violent. Almost all children, since they are very young, are exposed regularly to television shows that contain a lot of violent demonstrations. Although it is virtually impossible to calculate the number of violent acts that a child witnesses, it is estimated that, at the age of eight, children who watch commercial television have witnessed about twelve hundred thousand homicides and violent acts. Regardless of the validity and accuracy of these figures, it is indisputable that children watch much more violence on television than in real life. But it is not only the magnitude of television violence which harms the child’s development. Extensive research conducted by the National Television Violence Study, 1996, on American television programs, showed that three quarters of the violent characters were unpunished for any possible charges against them; Also, about half of violent acts on television showed no physical injury or suffering of any kind on the part of the victims. Therefore, children, besides running the risk of imitating the violent behavior seen on television, also appear to be implicitly encouraged by programs to take attitudes of this kind due to the lack of consequences for others and punishment for themselves.

The second group of scholars described television as a magic window that generates unseen horizons; opens the mind to contact another reality and discover new forms of behavior among which to choose. Regarding violence, all television would do is represent the normal dose of daily violence. According to the authors of this article, the effects on viewers are less tragic than what is defended by the “apocalyptic” vision and not as good as the theory of “magic window” defends because, in small doses, television can be a way to enrich the lives of children, but in large doses, it can take time that could be spent in social experiences. Therefore, it is not that television is harmful, but the use made of it.

Children are more affected than adults by cultural models to which they are exposed because they are in a phase of great change in which learning different concepts and values ??that will build their future identity takes place. TV is a model and encouragement for fun, comparing, discovering new phenomena. When watching a TV program, children come in contact with realities other than those to which they are used, they witness how diverse cultural stereotypes are accepted or ignored. Children do not remain passive while watching TV; a very young child is active when “he does something” and, similarly, when he just looks. It is important to keep in mind the child’s age, his ability to understand the broadcasted messages, the family and the social context in which he lives.

For these reasons, opinions about television should be supported by continuous assessment of what children see: only knowledge of the environment helps avoid it, build reading networks and get to identify quality criteria.

This is the purpose of quality control of television programs. It is a delicate work carried out with one’s head and heart, with precise instruments and testing through scenarios controlled by expert researchers. Demanding a qualitative control is a right, a duty, a necessity and a goal.

The attribution of responsibility for those programs that children watch on television is a social and political rather than legal problem. Our Constitution aims to protect children and the current history is full of rules.

The Statute of the duties and obligations of the operators of public radio and television services in Italy (USIGRai, 1990), notes that:

... In all actions concerning children, the first thing to consider should be: “the best interests of the child”, this prevailing on other interests (...) in all retransmissions of entertainment and advertising, those responsible for national television networks should take the rights of children into account.

The views of European and American TV viewers agree: there is pessimism about the ability of the State to ensure the protection of children; both the young and parents do not expect the state to protect minors; the role of responsibility is attributed mainly to producers and parents; some think it is important that children “learn to see the world” and that, therefore, there should be no protection. The latter rule out age as “criteria” and thus, in protecting children, they very often resort to an expert psychologist as a solution, as if childhood were a disease that needs treatment.

The rule states that broadcasters should improve the quality of programs, making contents-responsible management.

As evolutionary psychology experts, we believe that age has always been an important variable in human culture and that, over the centuries, it has been enriched by acquiring meaning, always paying special attention to the elderly and the children. The long childhood of human offspring and the protection associated with this age group has always been considered valuable. The child, in the legal system, has been clearly specified as a subject with enforceable and protected rights of effect.

The European survey in which respondents indicated those who produce videos and who raise children to be responsible stressed that responsibility for programs, as with any object, falls on those who produce them. Thus the child, like the program and like any other object, is the responsibility of parents. Thus, childhood is not a responsibility of all. Childhood is ignored once again and it is situated between two opposing stances:

1. If the child is an “object”, the responsibility falls to the parent and if the parent do not want the child to watch TV, just turn it off;

2. If the child is a “subject”, he will watch television, evaluate by himself and grow up anyway.

Of course, what we have learned about children makes us deny both positions. The child is not an object; we know that they are always active, even during their first months of life. They have the ability to choose and process. However, their growth is not complete. Thus, cognitive, emotional and social development of a newborn is not the same as that of a school-aged child.

Research carried out show great dissatisfaction and skepticism about the quality of television programs with a remarkable inability to recognize the attitudes and behaviors contained in the programs that are risky to children. Although it seems contradictory, parents and university professors and young people agree on these two criteria: firstly, they declare they are disappointed and critical of television programs and the use they make of children but, on the other hand, later, when they have to assess the situation, they have difficulty doing so. What happens is that conscientious parents, members of associations of TV viewers who have therefore had access to a minimum of information are not able to recognize the sexual signals, the vulgarity, the rudeness and manipulation of children. What they do is express a great sense of discomfort, although not expressly mentioned, perhaps the origin of the widespread skepticism of their views. He who laughs with vulgarity or attentively see violent scenes can, at the same time, experience discomfort and disapproval. International publications insist much on the skepticism of the user. But it is probably due to the feeling of discomfort, uncertainty and “alienation” that is often experienced when seeing rude, aggressive and vulgar scenes. They are short scenes and sensation does not become specific opposition but it surely reinforces general skepticism towards television and, by extension, to the rest of the media.

This can be surprising but, on the other hand, as researchers, we must admit that the speed of the media is such that it is often incompatible with genuine understanding. Also, there is no retransmission, especially involving children, which explicitly announces attempted manipulation, dissatisfaction, frustration and lack of respect for children. Only a possible repetition of the scene, in slow motion and with a debate would afford the possibility to recognize and isolate the episode that caused the discomfort. The adult, protective educator responsible for children during television programs is not considered an intermediary between the child and television. It makes more sense if the adult has the role of demanding that television respect children, a priori, as persons. It is therefore ambiguous that, in the last Code of Good Practices of the Television Industry (2003), the responsibility of the family concerning television is reiterated. It is important to establish where responsibility falls to. Families and schools are entitled to express their educational needs, so that programs being sleazy rude and with vulgar content and cannot be broadcasted. Today, parents are doomed to defend their educational project and to carry it out virtually on their own; It is not easy either for the parent or for the expert individually. The parent and the teacher are entitled to derive liability at the time in which the remote control is operated. Television in Italy exists since 1954 and, over time, local, national and satellite broadcasters have increased. The first specific industry regulations date from 1989-90 and since then, codes and laws have piled up and been juxtaposed. In the last code they already talk about child protection, quality of programs and the need for specific skills of the television workforce. But nothing is set about: who and how to train the television staff that will work for children and with what economic resources; who and how to evaluate visual and content quality and with what economic resources; who, how and with what instruments of analysis to examine the representation of minors that will inspire the treatment of minors by television.

The miraculous fact that all this can happen is up to the user, who must contact the Committee. But how can a single user, at a single glance and alone, recognize lack of quality, the danger of manipulation, lack of training of producers, the poor quality of the broadcast, lack of respect to minors and discomfort caused by vulgarity? It is skills and capabilities difficult to be implemented in a country with little tradition of research applied to the productive sectors. Nor can we endorse the “consumption” of television by industry experts that is often far from any structure intended to objective verification or experimentation as a scientific and effective. Demanding qualitative control is a right, a duty, a necessity and a goal. A right of parents and educators who are aware of the power of audiovisual media; a duty of broadcasters, which have recognized the need and are postponing their implementation; a necessity, because performing control can easily start an ethical way in which clear and measurable aspects that otherwise would be difficult and elusive are taken into account; an attainable and possible goal in a continuously way going from the child to the educational project. Programs with good visual, textual and educational quality are possible and achievable. Quality need not be more expensive than rudeness, violence and vulgarity.

1.2 The control model

Many theoretical contributions have highlighted the influence of television-proposed models on the behavior of children. According to the Social Learning Theory, the child learns simply by watching the actions of others. The ability of humans to learn through observation makes it possible to memorize information symbolically, without necessarily learning through direct experience. Children are, par excellence, those who learn through indirect experience or observation. Therefore, when watching stereotyped and minimally processed models and representations, minors can acquire cognitive patterns that do not favor proper psychological development.

The control model of television programs aims to extrapolate the rebroadcasted dominant models, or the characteristics of the various characters and explicitly and implicitly broadcasted messages.

In fact, it is vital that programs for children provide appropriate content to the cognitive, emotional and social needs of young users.

The offer of television for children should be free of stereotypes and be able to effectively communicate information on the topics dealt with, have structured stories with emotional content characterized mainly by a positive emotional tone or constructively resolved conflicts.

The objective of quality control is to point out the cognitive, emotional and social models proposed for children.

The control model crosses content variables, cultural models, assessment of educational, social and individual behaviors, affective and relational models.

Specifically, the objective is:

1. Identify the emotions experienced by the lead, supporting and antagonistic characters, and the emotional state generated in the viewer when watching the program;

2. Identify the values transmitted by the lead, supporting and antagonist characters;

3. Assess the coping strategies used by the lead, supporting character and antagonist characters to cope with stressful situations (stressors);

4. Detect the connotations frequently derived from the characteristic of the personality of the various characters;

5. Detect stereotypes.

Television rebroadcasts for children are analyzed individually by expert psychologists investigating various psychological dimensions that, more or less explicitly, convey behavioral models to be imitated.

The first examined variable in the model is represented by emotions. With the analysis of affective models, it is tried to define how the characters relate affectively to the others and the experienced emotions. The theoretical reference model is that proposed by Russell (1980), which presupposes the existence of a cognitive structure of affection consisting of interrelated categories. This is an appropriate approach to express the structure of emotional lexicon and emotional experience arising from the analysis of verbal relations; in general, it refers to the structure of knowledge of the ordinary man.

According to Russell (1980), this model identifies three fundamental properties of language and, more generally, of cognitive representation of emotions: the first refers to the fact that the like / dislike axis and the degree of activation are the main organizers of this area; the second refers to the fact that these axes are bipolar, so all terms and emotional concepts can be represented in varying degrees of intensity between the two extremes; The third property is given by the circulating system and, therefore, each term and every emotional concept, by having a certain place in space relative to the axes, can be defined as a type of like / dislike combination and degree of activation and, therefore, it can be identified in a precise manner in the corresponding quadrant. The proposed emotions are adapted whether those related to oneself or to the emotional state of others are valued. In this model, the different terms used to describe the emotions are distributed in a Cartesian plane having the pleasant / unpleasant and activator / inhibitor dimensions as axes. Experts were requested to identify both prevalent emotions of each character and emotion generally expressed by the program.

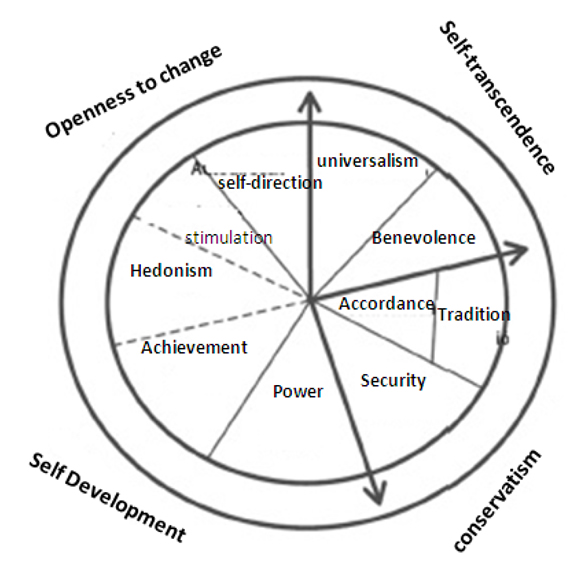

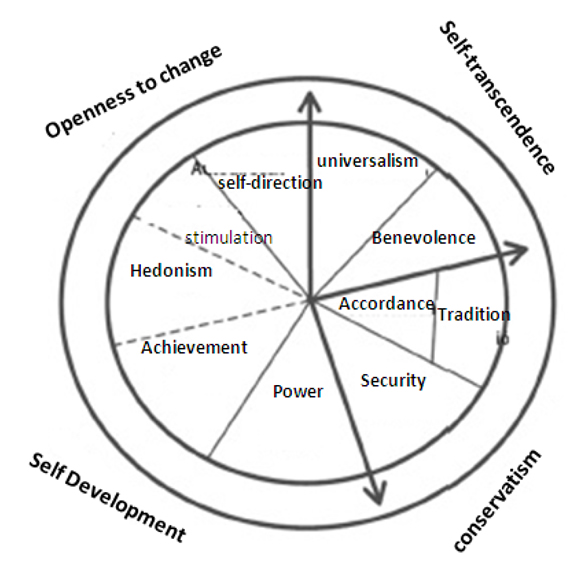

The second researched dimension is the values ??expressed by the characters pursuant to the model of Schwartz (1992), according to which values ??are cognitive representations of universal human needs: biological needs of the body, social demands and socio-institutional obligations. Schwartz identifies ten types of universal values ?? recognized in all cultures:

– power: social status and prestige, dominance over people and resources;

– achievement pursuit of personal success by demonstrating competence according to social standards;

– stimulation: taste for excitement, novelty and stimulating challenges;

– hedonism: pursuit of personal pleasure and sense gratification;

– self-direction: independence of thought and action;

– universalism: understanding, tolerance and respect for the welfare of people and nature;

– benevolence: maintaining and improving the welfare of people with whom contact is maintained;

– tradition: respect for and acceptance of the uses imposed by culture and religion;

– conformity: limitation of actions and impulses that may harm others and violate social norms;

– security: search for security, harmony and stability in society.

The model proposed by Schwartz has the ten values in space, following a circular arrangement. The more the strength of relationships among values decreases, the greater their distance. For example, universalism and power are at opposite positions because they have a negative relationship: the presence of one implies the absence of the other.

The set of ten values can be represented in a two-dimensional space. The first major dimension ranging from openness to change (self-direction and stimulation, hedonism) to conservation (tradition, conformity and safety); this reflects a conflict between the emphasis of independence of thought and one’s own actions and the preference for observation of practices dictated by tradition. The second dimension, from the self-benefiting (achievement and power) to self-transcendence (universalism and benevolence) shows a conflict between acceptance of others and commitment to their well-being and personal search and dominion over one’s fellow men.

Schwartz model allows us to analyze the values used in the programs and evaluate their polarization, so that more or less elaborate patterns of action are detected.

Figure 1: Model of Schwartz

Source: Made by myself

The third researched dimension is represented by coping strategies used by the characters. Coping refers to a set of useful skills to cope with and manage stress triggers in the environment (stressors). Frydenberg and Lewis (1993) defined coping as a set of cognitive and affective actions that occur in response to a concern and are an attempt to restore balance or suppress disturbance. In evaluating the programs, the following coping strategies have been taken into consideration:

– seeking social support: a character who seeks social support is primarily aimed at someone more competent to work out a problematic situation. You can seek help from the group of peers, parents or other responsible adults. This way of coping with stress is appropriate and typical of a person who activates his resources asking for help to those being more expert;

– escape / avoidance of the problem: a protagonist who denies the problem strives to actively seek ways to avoid the problem. The aim is to avoid thinking about the problem and use one’s own resources to reduce the importance of the troublesome situation and do not think about it;

– analysis and assessment of the situation: the character assesses the situation and makes a series of efforts to resolve the problem. The emphasis is on planning and the attempts to resolve the troublesome situation, ie strategies aimed at modifying the stress-triggering situation. This type of coping is generally considered adaptive;

– reserve it for oneself: the character, when facing a stressful situation, closes himself, often feeling discomfort and suffering from the frustrating situation, but he does not talk about it with anyone and does not look for a solution. He is in a state of paralysis that does not allow him to advance; he crashes.

– self-incrimination: the character blames himself and is considered the cause of the stressful situation, he feels demoralized by not keeping up and thinks about the error. This coping strategy is not functional as it is neither active nor operative;

– stress reduction: the character tries to calm down and reduce the time of tension caused by the stressful situation thinking how he can forget the situation in which he is immersed, calm down and think better. He concentrates on himself and not on the possible solution of the troublesome situation.

– self-transcendence: the character tries to calm down and reduce the time of tension caused by the stressful situation by going to an authority figure (divine or real) that can help him.

The fourth dimension analyzed in the quality control of programs for children is the personality of the main characters. We have already referred to the theory of the big five personality factors, McCrae and Costa (1989), one of the most common models in the study of personality. The authors proposed an explanation of personality that takes into account both factorial and lexicographical studies. These five factors are:

– energy: a very energetic character is characterized by a dynamic, active and energetic behavior and is often associated with extroversion, dominance and talkativeness;

– Friendliness: it describes altruistic, friendly, generous and empathetic characters, also regarded by others as being cooperative, friendly and nice;

– conscience: it describes very scrupulous, thoughtful, orderly, conscientious and persevering characters;

– emotional stability: emotionally stable characters are characterized by low anxiety, vulnerability and impulsivity. They are distinguished by their patience, scarce irritability and stable mood;

– open-mindedness: educated, curious characters full of interest and open to new experiences such as different cultures and customs.

Finally, in terms of cultural models, they have highlighted the stereotypes in programs, understood as schematic representations of phenomena that constitute a coherent reference for the life of an individual and a group because they influence the way humans act. Programs that have a stereotypical image of real life can help create unwanted prejudices in children about the role of women, ethnic minorities, foreigners, etc.

The stereotypes identified in programs can be of several types:

– sexual: female and male figures are represented in the program in a “conventional” manner. For example, the female figure has always been associated with a maternal and domestic role: she is dedicated to the care of children and household; she usually has a passive role within the family and, in case she has a profession, it is less qualified than man’s work. By contrast, the male figure is portrayed as dominant, rational and intelligent. While men are mostly lead actors, women are limited to admire them. The latter are represented primarily as focused on aesthetics, body worship and culture of appearance;

– geographic-ethnic: foreign ethnic groups or individuals are also likely to be represented in a stereotyped way. The difference regarding heroes stands out, ascribing to foreigners negative and socially undesirable characteristics: low sociocultural level, cruelty and violence, arrogance and unpleasant physical appearance;

– related to age: the characteristics that stand out in real life can be found in individuals belonging to different stages of development throughout life. For example, the figure of an elderly connotes wisdom and competence; children, helplessness and incompetence; teenagers, whim, exacerbation and obsession with their look;

– related to the profession: professional figures of high and low status are represented as extreme as to the tasks they perform and the social context to which they belong. For example, young people working in a fast food are simple and work very superficially in order to optimize time and production costs. Characters with prestigious positions are depicted as being in possession of the most advanced methods and tools, cars and luxury homes, a power that goes beyond the employment context in a strict sense.

1.3 Self-esteem and television models

The main scholars of communication processes have focused in recent years mostly on the most successful TV characters among young people, based on the assumption that it is possible to find in them the values, myths and models that contribute to the formation of their identity.

Reflection on television characters cannot do without an analysis of the symbolic imagery with which preteens are represented by the media and cannot avoid taking into account the values, myths and models proposed by the protagonists.

Television presents models that result in more “mythical areas” but are not necessarily shared.

Some authors allude to the concept of “identification”, a term that refers to the desire of minors to be a certain character. According to Cramer (2001), since preadolescence, identification is used as a defense mechanism to ward off the anxiety that comes from distancing oneself from parental figures.

An extremism of this mechanism could cause the preteen, who is always looking for new identification models, to want to imitate the character, he wants to be like him in real life. A more general concept is the “affinity” derived from preference for a character; affinity with one’s favorite character plays a key role in influencing the perception of the qualities and the ability of the subject itself and, therefore, self esteem, especially in those preteens who, being on the road to independence, are ready to de-idealize their parents and place their own idol on the pedestal.

Another important consideration is the parasocial relationship, this is the interpersonal relationship with the preferred character that stimulates feelings of intimacy and desire to maintain and strengthen that relationship, albeit one-sided. We have identified a number of elements that characterize the level of participation of minors with their favorite character:

a) Entertainment and social fun: fans are attracted by the celebrity, for what he does and how he does it (“I like talking to my friends about what my favorite character has made “).

b) Intense feelings toward the celebrity: similar to obsessive tendencies of fans (“I consider my celebrity my friend” or “I often think about my favorite character, even when I do not want”).

c) Worshipping the celebrity: as an extreme expression defined as pathological borderline. It shows a pathological social situation and behavior resulting from exaggerated worship of a celebrity ( “If I had a lot of money, I would rather spend it buying a personal items used by my idol,” or “If I were asked to do anything illegal for my idol, I would probably would”).

In some circumstances, preference relations with a character of the showbiz can have a positive impact on the self-esteem of the subject, whereas in others they can lead to demoralization and a decrease in appreciation of one’s own talent.

For some people, celebrities have no effect on the perception of oneself: for example, a person can see the excellent performance of an athlete at the Olympics, without experiencing any variations in self-confidence.

According to Rosenblum and Lewis (1999), in preadolescence, identification models proposed on television have their greatest impact on body image of youth and take on a primary role in the development and alterations of eating behavior, such as anorexia and bulimia. Smolak and Levin (2001) found in preadolescence a significant positive correlation between prolonged exposure to watching television stimuli with thin models and an immediate sense of bodily dissatisfaction; girls with a history of eating disorders or high scores of dissatisfaction with their bodies are more susceptible to images of thinness.

2. OBJECTIVES

We have analyzed the role of self-esteem as a protective factor in the choice of one’s favorite character; the possible moderating effect that this can assume on the cognitive and affective determinants that support the choice of that character.

The intention is to explore how the preteen places himself regarding the path of the construction of identity and verifies whom to attribute the ability to represent his values.

We intended to verify whether subjects with different levels of self-esteem differed:

1. In preparing the preference for a celebrity.

2. In the selection of objects that evoke the link with the preferred model.

3. In the description of the characteristics attributed to oneself and to the favorite character.

3. METHODOLOGY

The group is composed of 800 preteens (400 boys and 400 girls) students in last year of junior high school in Rome and province. The average age of the subjects is 13 years (SD = 0.78).

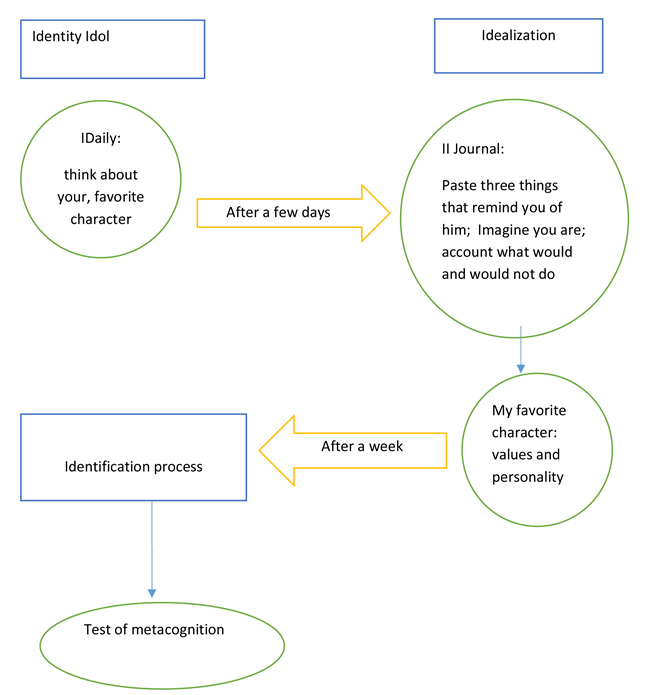

“Start thinking about your favorite character” is the first indication, in class, and they were given an individual diary to take home and complete during the first week. Then, in class, the kids were invited to complete self-assessment questionnaires.

The realization of the diary serves to inquire about the strength of the preferred character and the ability to recognize themselves in it. The time for reflection has been long: they were given a week to collect objects and think about their favorite character.

The diary serves to encourage kids to think about their favorite character; they should stick three things (photos, newspaper clippings ...) representing the character; introduce the character (name, profession ...) and justify the choice of objects associated with the representation; tell what they would do or would not do for a whole day if they were chosen character.

“My favorite character” is a questionnaire consisting of 77 items and articulated into three sections to analyze the characteristics of the identification of preteens with their favorite characters.

“Section 1” asks about the characteristics of identity, profession of parents, television consumption and choice of favorite character in particular, taking into account temporal stability and likeness.

“Section 2” asks about the characteristics of preference, cognitive complexity and breadth of emotional involvement.

“Section 3” investigates the personality characteristics of the examined subjects and of their favorite character through a list of 15 adjectives. Subjects are requested to indicate, among other things, a value and a defect in common with their favorite celebrity.

For the assessment of self-esteem, we have used TMA (Bruce A.Bracken, 1993-2003) that investigates six specific areas: interpersonal relationships; capacity to control the environment; emotionality; school success; family life; vital experiences.

Of all these six areas. a total score of global self-esteem is obtained. The instrument, which has been used in previous research, has shown good validity and reliability rates.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1 What effect can tv celebrities have on self-esteem?

Compared to the first question, if preteens have a favorite or not, out of a total of 800 subjects, there is no single negative answer. The favorite character is an absolute rule that no preteen skips.

All subjects have developed a preference for a character: this happens in all cases concerning television as it has happened in other stages of development when it comes to express a choice or preference. Even for this group of subjects, one can speak of widespread preference: all “prefer” but every preteen decides to choose a different character.

The character chosen by the girls is a female in 45% of cases, while about 98% of boys choose one character of the same sex. The results coincide with those of Kathryn et al. (2004), which show that female minors mostly choose famous characters of the opposite sex. The data, confirmed by the literature that has dealt with adolescence, seem to suggest that the favorite character performs functions not so much related to sexual identification, but rather to social status and professional achievement.

As for the area in which the identification is carried out, most preteens choose a character of the showbiz and sport. Almost all have a strong preference for a celebrity, that is, by a character known to everyone.

Therefore, given these results, it was determined whether preteens with different levels of self-esteem were different also in the choice of their favorite character.

Out of the total sample, two groups of subjects were selected:

a) preteens with high self-esteem scores (2ds above average);

b) preteens with low self-esteem scores (2ds below the mean).

The two groups are composed of 80 subjects (48 boys and 32 girls) and 55 subjects (20 boys and 35 girls), respectively.

Even for these two groups of subjects, preference is widespread and not shared. For both groups, there is a profile of preferences that are not dense in substantial actions in favor of a moderately winning character.

4.2 Idealization

We examined whether preteens with high and low self-esteem differed in the choice of objects collected during a whole week, referring to their favorite character.

Subjects with high levels of self-esteem, in 75% of cases, have not reported any object or a sign of a different link, it is a very weak, almost nonexistent idealization.

Individuals with low self-esteem have collected a larger number of objects (mean = 2.6) than those with high levels of self-esteem (mean = 0.72): the latter seem to be far from the idealization of their favorite character.

Regarding typology, most of the subjects with low self-esteem have collected photographs, followed by newspaper clippings and magazines as a second object.

4.3 The parasocial relationship

Different concepts have been used to illustrate the relationship with television characters. These include a historically consolidated model derived from studies of idols: it is the parasocial relationship, that is, the illusion of an interpersonal relationship with the character that causes a feeling of intimacy and a desire to maintain and strengthen this bond since, although the interaction is unilateral, the person perceives the character as a friend.

The definition of what would preteens do if they were their favorite character is different depending on the self-esteem parameter: subjects with high levels of self-esteem could help those who are in trouble and would carry out work without neglecting family ties and friends. People with low self-esteem do not want obligations and would like to spend time in beauty parlors:

“It’s not easy to stay beautiful and famous. I think I should make sure the whole day that I’m always good for my fans and they find me fascinating. I don’t want to end up like Britney Spears ... I won’t take any drugs because drugs make you ugly and you don’t have strength to go on. you have to keep your look. And then, if I could, I would have surgery ... but with a good plastic surgeon so that almost nothing is noticed later. When I see the models on television, sometimes they forget them. If I were my character I would do it because I would have the money to choose a good surgeon to adjust me without anyone noticing.”

«I would like to be in Corona’s stead ... who has so many girls wanting him. Well, maybe he is handsome because he cares about spending a lot of money to be handsome. The photo I put in the diary is he leaving a store in the center of Milan and he has spent more than 500 euros in products to be handsome. My father tells me that he is just one who has stolen a lot of money, but I don’t care ... he manages with women, and I would like to be in his stead.»

As many researchers say, television is an influential source of images and messages about the idealized body that children aspire to achieve. Favorite characters from entertainment programs are meaningless and lack responsibility; however, they operate in the social representation of the boys: they are models for their future, they inspire kids in their personal situations and, therefore, these characters have a key role in their lives. And they are really weak models without any purpose, memories or cognitive constructions, without the force of example of behavior that nevertheless inspire preteens in particular situations and thus play an important role in development.

4.4 Identification

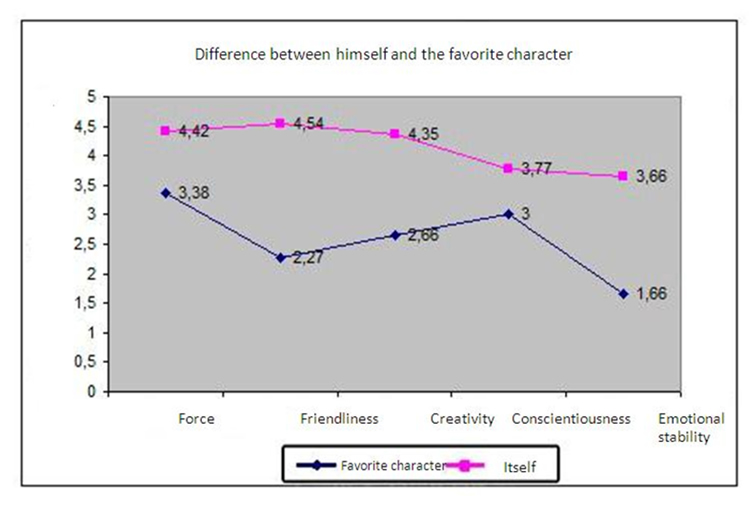

It is interesting to note that children with high levels of self-esteem describe themselves as stronger, more sociable, creative, aware and emotionally stable than their favorite characters.

The construction of the “character” uses a representation of the characteristics of their own personality separate from models.

Figure 2: Subjects with high self-esteem

Source: Made by myself

Individuals with low self-esteem feel they are less energetic, creative, sociable, aware and emotionally stable than their favorite characters. They attribute what they themselves do not possess to their favorite character.

Figure 3: Subjects with low self-esteem

Source: Made by myself

4.5 The role of metacognition

While many researchers have highlighted a number of risk factors linked to the identification and parasocial relations that preteens can establish with characters created on television, there is still lack of searches that delve into the role of metacognition as a protective factor, ie, the knowledge of a subject of his own cognitive functioning and of others’. Metacognition is an activity that regulates cognitive functioning in solving problems and can prove to be very important in meeting the need of the preteen to take models from the television experience.

The attribution of mental states of other people, as well as reflection of their own mental states are basic cognitive operations that require, as well explained by the model of the Theory of Mind (ToM), not only the representation of mental states but also the ability to simulate, in oneself, what other people think and feel (Astington, 2001). Identifying the purpose of mental activity, considering the source of error and difficulty can be considered essential components of metacognition and a useful reflection on the characteristics of the activity of thinking.

The issue of understanding the intentions of others is of great interest in developmental psychology. The latest research shows child’s early ability to distinguish between the actions of animate and inanimate agents and attribute mental states, desires and intentions to animate agents. Research in this sector has had tremendous momentum in recent years, especially through the creation of ingenious experimental processes that allow us to test understanding of the mind in an ecologically valid way without resorting to language (Behne, Carpenter, Call and Tomasello, 2005).

As pointed out by Behne, Carpenter, Call and Tomasello (2005), the study of how children understand the failed attempts and accidental actions of others is particularly interesting in that the child is shown models in which intentional actions are separated from the role of the actor. Currently, the most obvious examples about understanding failed intentional actions and accidental actions come from imitative paradigms. Another response of Meltzoff experiment on imitation was made by Johnson, Booth and O’Hearn (2001) who, for their empirical research, used a nonhuman-looking researcher disguised as an orangutan, who interacted with the child. The test was conducted with children aged 15 months, who proved to be able to mimic both the “successful” and the “failed” actions of the orangutan.

In other words, accepting the theory of mind means knowing that the behavior of each one must be read and interpreted on the basis of mental states: ie the desires, emotions, beliefs, feelings and thoughts that normally guide one’s own social conduct. (Behne, Carpenter, Call and Tomasello, 2005)

The principles of this theory are:

1. Consider others as having mental states;

2. Maintain that there is a causal relationship between these mental states and events in the world.

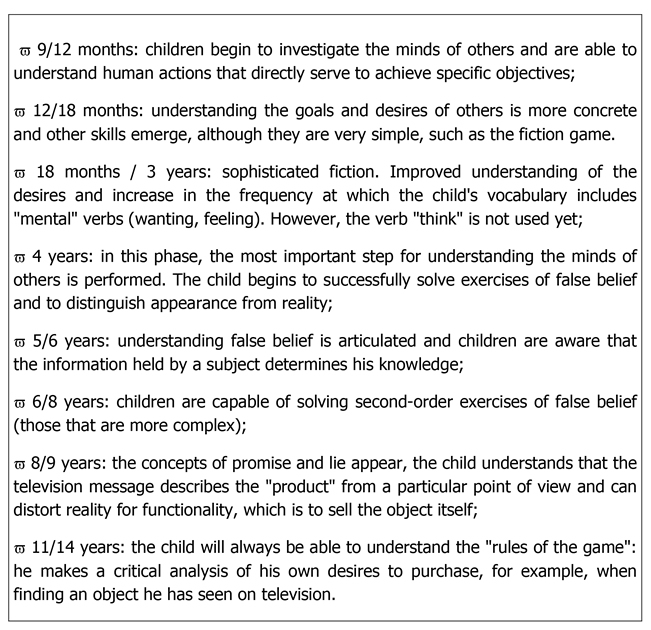

But at what age the child is able to attribute desires and beliefs to others? Research suggests that, around 4 years, the most important step for understanding the minds of others takes place. The theory of mind is structured through the development of a series of pre-existing concepts such as shared care, intentional communication, imitation games and fiction games. The experiment of Sally and Anna is frequently used to illustrate understanding the minds of others and the correct attribution of beliefs.

Figure 4: Exercise of Sally and Anna

Source: Made by myself

Three-year-old children generally fail in this exercise, they answer that the ball is in the place where it is actually located and not where Sally thinks it is. At this age, the child attributes the behavior of Sally not to what she knows to but what the child has seen.

Instead, the 4-year-old child is able to give a correct answer The child attributes the behavior of Sally to what she thinks, that is, to her belief that the ball is in the basket.

Figure 5: Phases of development according to the Theory of Mind

Source: Made by myself

Through research conducted to understand the favorite characters of preteens, we wanted also to explore the role of metacognition.

We have used the same methodology as the logbook and questionnaire about favorite characters with a group of 500 students (300 boys and 200 girls) in the last year of junior high school in Rome and province. The mean age of subjects was 12 years (SD = 0.67). The scale used to measure metacognition (D’Alessio, Laghi and Pallini, 2007) consists of 24 items and it is articulated in:

1. Planning, understood as the ability to act in solving a problem and in developing the solution strategy.

2. Control, ie the ability to assess the outcome depending on the purpose and the ability to abstract information about the outcome of one’s own actions.

Figure 6: Development of research

Source: Made by myself

Also for these subjects, having a favorite character is a maximum rule. All of them have developed a preference for a character and, in all cases, from television. The preference has been distributed over 206 characters and only 3 with a rate above 5% coincidence. Also in this group of subjects, we can speak of dispersed preference: we all choose, but only teenagers choose a different character. The preference behavior of preteens does not differ much from adult consumers surveyed by Anderson (2006), who demonstrated how the curve of consumption in them, where there is a variety to choose from, music or movies, is not located according to the curve defined as “normal” characterized by peaks product of shared success. In fact, the Gaussian curve (or shortage) represented only preference on a limited range of products. Preteens, even if they are exposed on television to a more limited number of products with regard to consumers of music or movies (who, on the Internet, can choose from more than a thousand options), produce a curve that is no longer Gauss’s, where individual choice - long tale - represents more subjects; there are no shared characters, only one with a percentage of 7%, as all other choices are almost entirely single or individual preferences.

Figure 7: Long tale election of idols by teens

Source: Made by myself

The dispersed choice seems to have a common element, but it refers to a quality that the evaluating subject chooses from the huge existing offer. Preteens choose, but their choice is not motivated by a specific cause. There is much dispersion in preference, below the threshold of 5% of shared choice. The percent of preference for unshared characters is clearly higher than that of the most selected shared character. What produces a reversal of the distribution performed by Pareto, who saw sharing preferred elements as an explanation of the distribution of purchase: with 20% of the products that covers 80% of sales.

Given these results, we can assert that the distribution cannot be defined more as Gaussian. The normal (or Gaussian) distribution is important because many variables derive from the sum of behavior, in which case the value is centered on the “norm”, that is, the values ??that deviate from that can be considered casual “errors” that are approximately distributed as a curve. Therefore, the normal curve is also called “curve of errors”. As an example, the reading ability, being introverted, satisfaction at work or memory capacity are some variables that are approximately distributed and in a normal way.

Analyzing the pleasantness of characters, we have found a long tale distribution. The rare events (in the case of the favorite characters of teenagers) can cumulatively outnumber or be more important in the initial part of the curve, so that, putting all together, they would represent the majority.

The market of wealth and technology allow consumption of the individual selection. The cultural filter no longer works and has been derived from subject to object. The first is free without the cultural anchor in front of the television.

Thus, out of the total sample, two groups of subjects were selected:

1. Preteens with high score in metacognition (2ds above average)

2. Preteens with low score in metacognition (2ds below average)

The groups are made, respectively, of 58 subjects (28 boys and 30 girls) and 63 subjects (30 boys and 33 girls).

Also for these two groups of subjects, preference is dispersed and unshared: in both groups, we have a profile of single preferences.

4.5.1 Identification of metacognition

It is interesting to discover how subjects with high level of metacognition are described as strong, friendly, creative, conscientious and comfortable about their own favorite characters.

Figure 8: Subjects with high level of metacognition

Source: Made by myself

Subjects with a low level of metacognition claim to be less energetic, creative and comfortable about their own favorite characters and, at the same time, braver.

They attribute the quality of which they have little to their favorite character.

Figure 9: Subjects with low metacognition

Source: Made by myself

Most preteens with a high level of metacognition state that they have nothing in common with their chosen favorite character (77.59%) and, in the few examples, few features of competence and capacity (8.62%) are evident.

It is interesting to discover that they feel more aggressive and braver than their favorite characters. That is, they have collected the message related to the construction of television characters; they are people equal to others, but more resolute and, therefore, it is willpower, not capacity, what determines a fact.

Figure 10: Subjects with a high and low level of metacognition in relation to their own estimate of resemblance to their favorite celebrity.

Source: Made by myself

Preteens with a low level of metacognition behave in a diverse way in relation to the group of subjects with a high level of metacognition; They claim to be similar to their favorite character in perseverance, determination and capacity. Instead, the other group values themselves much more because they are not identified with their character and state they have nothing in common (77%).

5. CONCLUSIONS

The choice of identification models seems to be connected to the evaluation and judgments about themselves made by preteens, management of corporeal and social image.

Long ago, Erikson (1968) introduced the concept of “secondary attachment” as a transition phase from the link with parents to the link with peers. The exercise of attachment developed at this stage leads to an increase in emotional autonomy of the subject. The secondary attachment to a favorite character drawn from the media often is due to an agreement on a “parasocial” relationship in which, however, all interactions are one-way; the individual perceives intimacy, an approach to the chosen figure in such an approach that the individual comes to feel the character like a friend (Giles, 2005).

The media produce cultural material for the development of gender identity, building opinions and beliefs, spreading pieces of romantic and sensual experiences. For example, a typical loving exercise or the typical childish relationship with a singer or some fictional protagonist can push the subject to implement an imaginary elation, as a general proof of an adult relationship.

The approach to idols favors detachment from parental figures, ie, it allows the phase of de-idealization of the parents to begin. Many researchers argue that this stage represents a necessary phase in the process of individualization; after depriving one’s parents of idealization, one begins to create a space within which the figures and characters of the media may come to be influential models in the normal development of the preteen.

The preteen will be searching for models, and television, with its explicit messages, though they are also implied, will make the proposal of values, opinions and behavior that the preteen can take. Television is therefore an unlimited source of potentially adoptable models of behavior.

The identification process is gradually shaped with age, preadolescence is not just a phase since it carries its own characteristics. The celebrities proposed on television offer a variety of possible “I” that a preteen or teen may want to import into their personalities and create examples of “how to think and feel in different circumstances.” This, in a sense, and although not always shared, inevitably comes to be part of everyday life.

Rosenblum and Lewis (1999) established potential risk factors, because the identifying models proposed by television in preadolescence have a huge impact on body image and assume a primary role in the development of alterations in eating behavior such as anorexia or bulimia. Through the few pieces of research that have explored the relationship between the identifying models proposed by television and bodily experience in men, it has been shown that men are more attracted by the capabilities of their favorite character (in most cases, the idol belongs to the sports world) than by the ideal of a lean, muscular body, which is selected only in adolescence.

The results of this piece of research show how subjects with low and high self-esteem are not so much different in their choice of a character and in the emotional and cognitive role the relationship entails.

While it is not possible to establish a relationship between self-esteem and the concept of “I”, it is possible, instead, to differentiate between self-esteem and personal values, with a possible variation of personal values over time and constancy in time of self-esteem in general.

According to Shavelson (1976), the concept of “I” can vary depending on the various fields of experience and as such it can be defined as a multidimensional construct.

The various dimensions of the concept of “I” are organized and structured hierarchically and they influence the level of global self-esteem.

In line with the concept of Shavelson, Bracken (1992) maintains the concept that “I” is constructed in a multidimensional and context-dependent manner, which reflects the personal evaluations of past experiences and influences behavior. Especially in preadolescence, self-esteem can assume protective functions as well as metacognition.

In recent years, many researchers have associated the development of theory of mind with the natural ability of metarepresentation, such as metacognition. According to the theoretical model of Khun (2000), the Theory of Mind and metacognition can be considered two different indicators of meta-knowing, ie of metaawareness, definable as any cognitive act aimed at one’s own of others’ mental activity.

If we consider the Theory of Mind and the ability to use mental representation to predict one’s own and others’ behavior, metacognition is a competition that does not exist independently in the mind of the person but distributed in the network of emotional and social relationships in which the individual participates and gains in experience.

These emotional and social relationships of the preteen can, however, also be one-way, such as those established with TV characters. We speak of parasocial relationships that have been little explored in the scientific literature: relationships that influence the mental capacity of the subject as they are focused on the network of characters with simplified and partially shown values ??and life styles. The results of this piece of research show how subjects with low and high levels of metacognition do not differ in their choice of the character and the emotional and cognitive level that connotes the relationship.

What differentiates the two groups of subjects is the ability to mentalize, that is, the one that Fonagy and Target (1997) defined as reflective function. When the preteen recognizes himself, his mind is able to actively mediate in the interpretation of reality on television and he has the ability to re-read the “I” in the proposed story with critical skills.

At this stage of development, passing from motor-perceptual intelligence to formal logic represents a turning point in one’s growth, since the preteen uses mental images and symbols to exercise representative capacity to operate in formal contents by relating them. The thinking of boys being older than 10 years is freed from the limits of perceptual data to start the network of deductive, formal and hypothetical reasoning. The ability to make representations of events and events that happened in the past is the first intellectual autonomy with the consequent need to do it by oneself, to exercise one’s ability to reconstruct the received beliefs and views. It is voluntary marginalization of personal development, or the usual crisis of functional originality in the development of personal attitudes, all of them being derived from the sense of what is possible: personal, social and universal context.

Thus, the level of metacognition of the child will be determinant, as has been evidenced by this piece of research, to identify oneself with the social references made on television.

Most preteens with a high level of metacognition state that they have nothing in common with their favorite chosen character, which shows they understand the concept of building a fictional character and, therefore, they do not feel the celebrities as part of their own life, demonstrating a high level of self-esteem. Instead, preteens with low metacognition claim to be very similar to their celebrity; therefore, they establish a link with the celebrity by integrating it as part of their own life, showing a low level of self-esteem.

6. REFERENCES

1. Anderson, C. (2006). The Long Tail. Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More. New York: Hyperion.

2. Astington, J. W. & Barriault, T. (2001). Children’s Theory of Mind: How Young Children Come To Understand That People Have Thoughts and Feelings. Infants & Young Children, 13(3), 1-12.

3. Behne, T.; Carpenter, M. & Tomasello, M. (2005). One-year-olds comprehend the communicative intentions behind gestures in a hiding game. Developmental science, 8(6), 492-499.

4. Bracken, B. A. (1992). Multidimensional self concept scale. Pro-ed.

5. Bracken, B. A. (2003). TMA. Test di valutazione multidimensionale dell’autostima. Edizioni Erickson.

6. Cramer, P. (2001). Identification and its relation to identity development, Journal of personality, 69(5), 667-688.

7. D’Alessio M.; Laghi F. & Pallini S. (2007). Mi oriento. Il ruolo dei processi motivazionali e volitivi. Padova: Edizioni Piccin Nuova Libraria

8. D’Alessio M. & Laghi F. (a cura di) (2007). La preadolescenza: identità in transizione tra rischi e risorse. Padova: Edizioni Piccin Nuova Libraria

9. D’Alessio M.; Laghi F. & Froio M. (2007), I modelli dei preadolescenti: uno, nessuno o centomila?, in M. D’Alessio; F. Laghi (a cura di). La preadolescenza: identità in transizione tra rischi e risorse. Padova: Edizioni Piccin Nuova Libraria

10. D’Alessio M. & Laghi F., Preadolescenti e modelli identificativi proposti in TV, in A. M. Disanto (a cura di) (2006). Percorsi di crescita oggi: itinerari accidentati. Roma: Edizioni Scientifiche Magi

11. D’Alessio M. & Laghi F. (2006). Maneggiare con cura. I bambini e la pubblicità. Roma: Edizioni Scientifiche Magi

12. D’Alessio M.; Laghi F. & Baiocco, R. (2006). Identity process in early adolescence: metacognition and Theory of The Mind. Intersubjectivity, Metacognition and Theory of Mind, Università Cattolica, Milano (Italy).

13. D’Alessio M.; Baiocco R. & Laghi F. (2007). The impact of Television on Children’s Eating Behavior and Health. XIIIth European Conference on Developmental Psychology. Jena, Germany, 21-25 August.

14. Derbaix, C. & Pecheux, C. (2003). A new scale to assess children’s attitude toward TV advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 43(04), 390-399.

15. Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity. Norton.

16. Fonagy, P. & Target, M. (1997), Attachment and reflective function: Their role in self-organization, Devel. Psychopathol., 9, 679-700.

17. Frydenberg, E. &Lewis, R. (1993). Manual: The adolescent coping scale. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research.

18. Giles, D. C. (2005), Parasocial interaction: a review of the literature and a model for future research. Media Psychology.

19. Johnson, S. C.; Booth, A.& O’Hearn, K. (2001). Inferring the goals of a nonhuman agent. Cognitive Development, 16(1), 637-656.

20. Kathryn E. et al. (2004), The Relation Between Chosen Role Models and the Self-Esteem of Men and women. Sex Roles, 50, 575-582

21. Kuhn, D. (2000). Theory of mind, metacognition, and reasoning: A life-span perspective. Children’s reasoning and the mind, 301-326.

22. McCrae, R. R.& Costa, P. T. (1989). The structure of interpersonal traits: Wiggins’s circumplex and the five-factor model. Journal of personality and social psychology, 56(4), 586.

23. Morgan, K.& Hayne, H. (2002). Age-related changes in visual recognition memory from infancy through early childhood. In International Conference on Infant Studies, Toronto, Canada.

24. Piaget J. (1936). La naissance de l’intelligence chez l’enfant, Delachaux e Niestlè, Parigi, trad. it. (1973), La mascota dell’intelligenza nel fanciullo, Firenze: Giunti e Barbera

25. Piaget J. (1937). La construction du reel chez l’enfant, Delachaux e Niestlè, Parigi, trad. it. (1973), La costruzione del reale nel bambino. Firenze: La Nuova Italia,

26. Rice, M. L.; Huston, A. C. & Wright, J. C. (1982). The forms of television: Effects on children’s attention, comprehension, and social behavior. Television and behavior, 2, 24-38.

27. Rosenblum, G. D.& Lewis, M. (1999). The relations among body image, physical attractiveness, and body mass in adolescence. Child development,70(1), 50-64.

28. Russell, J.A. (1980). A Circumplex Model of Affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1161-1178.

29. Shavelson, R. J.; Hubner, J. J.;& Stanton, G. C. (1976). Self-concept: Validation of construct interpretations. Review of educational research, 46(3), 407-441.

30. Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in experimental social psychology, 25(1), 1-65.

31. Smolak, L. & Levine, M. P. (2001). Body image in children. Body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth: Assessment, prevention, and treatment, 41-66.

AUTHORS

Javier Fiz-Pérez

Social Bioethics Professor. He is currently the Head of the Department of Developmental Psychology and Education at the European University of Rome and a Delegate to International Research Development.

Psychotherapist (N. Referee: 16893, Italy), he is Scientific Co-director of the Laboratory of Psychology applied to Work and Organizations. He collaborates with the European Institute of Positive Psychology (IEPP) as scientific officer. He is scientific director of the Editorial collection “Lo Sviluppo Integrale” – Persian Editor-, Bologna, and author of many national and international publications.

Gabriele Giorgi

Psychologist and PhD, she is a researcher and associate professor in the scientific field - M- PSI / 06- of occupational and organizational psychology at the European University of Rome. Over the years, she has conducted research on major national and international companies and has conducted surveys in various countries around the world. She is Co-director, with Prof. Francisco Javier Pérez Fiz, of the Laboratory of Commerce and Health, of the European University of Rome.

Blanca Sánchez-Martínez

Journalist, PhD Research at the Complutense University of Madrid. She currently teaches at the Editorial Sector for the Community of Madrid. Her research is related to multicultural communication, as well as in the Arab World and Security and Cooperation in the Mediterranean